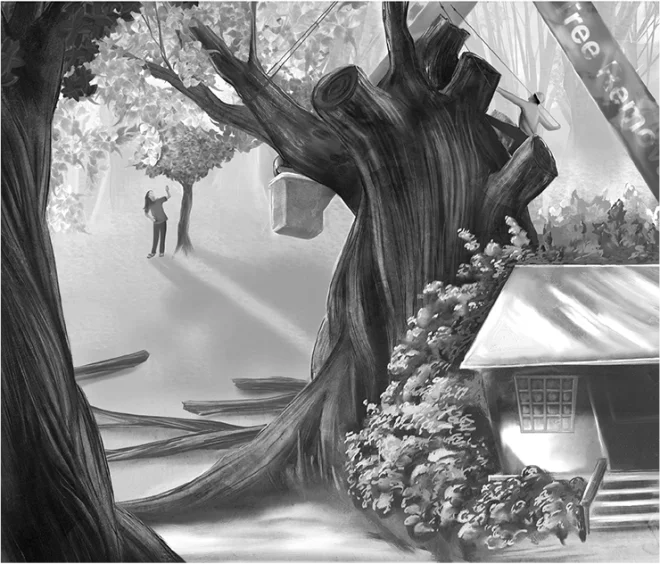

Last May, the young man who lives in our garage cottage showed us a huge loose limb hanging over his roof, large enough to crush, at any moment, the cottage, not to mention our tenant.

The tree man, who came immediately, confessed that he had thought I was exaggerating when I described our tree, with a trunk nearly five feet in diameter and branches towering 60 feet high above the little house. He said he had never seen a Zelkova that large.

The Zelkova, or Caucasian Elm, was rather a rare tree when planted by my parents-in-law over 60 years ago. The English or American elms had mostly died or were dying from Dutch elm disease. This elm doesn’t get the disease and, like other elms, is a good shade tree and grows quickly. It’d have been perfect for the job of shading and cooling the cottage—but they planted it only 15 feet away from the living-room wall, and it grew well—very well.

It is almost impossible when planting a young tree to envisage its potential. If you really give it enough room, you seem to end up with a forlorn sapling in an empty space—like a little lost kitten in a banquet hall. How is it that small creatures, from teeny crocodiles hatched from eggs to the cuddly bundles that became my six-foot sons, could do this? And the time it takes for this transformation flies away in a flash.

So the immense tree reaching up to the heavens, just sprouting its first bright spring leaves—majestic, lord of the world—would have to go. Topping it, we were told, would deform and weaken it and was a very short-term solution. Girding it with cables would be ugly and would not guarantee against damage. So we made the (very expensive) decision to take it down. While we waited, whenever I looked at it my heart would seem to break. The best we could do for it was to offer a local furniture maker any wood that might give our tree an afterlife (of sorts).

Well, the day came and early I went out: “I’m sorry. I am so very sorry.” If only it had been planted farther away from the cottage! It had grown and provided shade and havens for birds and animals. We had erred—and it would pay the price.

The trucks arrived, and the green spring leaves stirred with the breeze they made: a huge bucket truck; a vast machine to grind the wood and pour it out in chips; a small tractor; a truck full of equipment; five men to manage all this. I left for a while.

When I came back, the bucket was 60 feet in the air and a nonchalant man was sawing off limbs with brilliant precision, seeming to be able to rope each falling branch so it fell in exactly the right place. The others fed the chipping machine or sawed the limbs into huge logs. The tractor grabbed the logs and stacked them neatly. The uncut branches quivered, waiting their turn.

I had thought I wouldn’t watch—but I couldn’t tear myself away. There, in all its majesty, was the vulnerability of the tree. And there was the miracle of these tiny men turning it into logs and sawdust with the grace and precision of circus dancers, skimming up limbs, watching for just where a branch would crash down, hitching ropes, pulling, sawing, and doing all this with nothing damaged.

The tree did not go quietly. The noise was excruciating. Limbs ripped off with bark. Chainsaws whined. The grinder spewed a fountain of chips into the woods. The air was thick with sawdust, and the five men gestured and shouted, seeming to understand each other’s moves like medics in a trauma center.

I sat. I missed lunch. I couldn’t go away as branch after branch crashed until finally there were only two high ones left, reaching skywards. I waited for the tiny figure in the bucket to reach them. He was smoking with one hand, brandishing the chainsaw with the other. I waited.

I was sitting at the edge of the lawn, backed by brush. I was still waiting, looking upwards, when I chanced to glance back behind me at a tangle of brush and ivy. Then quite suddenly I noticed a familiar leaf in the tangle. A young Zelkova, about 15 feet high, was almost smothered by the undergrowth.

I ran for the house and grabbed my pruners and frantically chopped at the ivy and the brush, pulling away at the vines. The little tree emerged. It was growing in exactly the right place to give shade to the cottage and not be too near anything. It had planted itself, with no help from us and, yes, it was free.

Meanwhile, the man in the bucket had reached the last massive branch. He began to saw, and underneath everything was quiet as we all waited for the last huge branch to crash down. Well, I suppose it was my imagination, but it seemed to me that the leaves on my little tree stirred, perhaps trembled. High up, touched by the afternoon light, the last leaves on the last great branch seemed to be moving, too—in recognition. ❖

Previous

Previous