It’s summertime, and as usual, my winter houseplants are crowding my porch. They are so spoiled—but some of them have been with me for almost half a century, dating back to when my mother-in-law lived with us. She died, about this time of year, more than 18 years ago.

Two of these houseplants are actually named for mothers-in-law: the Sanseviera trifasciata and the Dieffenbachia sequine. The former is commonly called mother-in-law’s tongue (or snake plant) and the latter, mother-in-law plant.

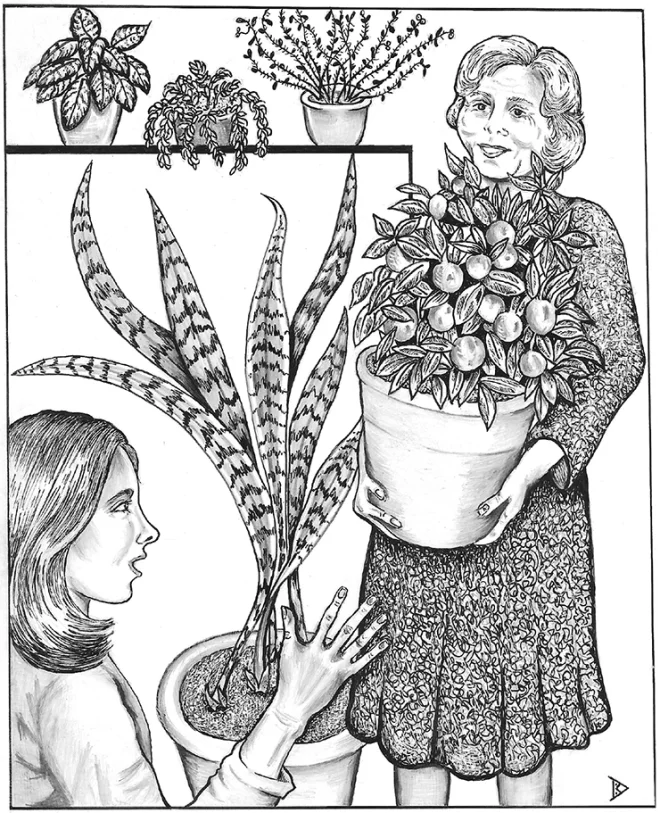

My own mother-in-law, like probably most of her kind, seemed to irritate me and touch me in equal proportions. When there were dishes to be done, she suddenly became very old and very tired, palely collapsing on to her chaise lounge—appearing as if death were imminent. But I remember her, too, staggering in one Christmas with a magnificent Meyer lemon tree , which all but enveloped her (she was not a large woman). I had admired it when we were out together—and she had bought it for me. I still bring it out each summer along with the other houseplants, and every winter I make lemon marmalade.

I remember, though, another occasion when I spilled bleach on my husband’s favorite shirt. I came to him to confess having done “a terrible thing.” He listened gravely—then his face changed to one of smiling relief. “I thought you were going to tell me you had pushed Mom down the stairs.”

What is it about mothers-in-law? The mother-in-law’s tongue (one of the best plants for filtering formaldehyde out of the air) is apparently so named because it has sharp-toothed, tiger-striped leaves. The leaves are tough, too—the fibers of some species can be used to make stout ropes. Its common name overshadows its botanical one, which derives from a long-forgotten Italian prince of Sanseveiro. The mother-in-law plant is apparently so called because an enzyme in its leaves can (if ingested) cause a swelling of the tongue and even speechlessness. Another name for it is dumbcane. Its botanical name is for an obscure Austrian botanist, J.F. Dieffenbach, who worked in the public gardens at Schonbrunn.

In fact, my own mother-in-law did not have a sharp tongue—or cause speechlessness. On the contrary, she was as sweet as could be. So sweeet that it took me years to realize that she and her sister (who lived nearby) used charm to nearly always get their way. They were Southern ladies raised in a culture with which I was totally unfamiliar. In my family, we might yell and scream, but we (usually) reached a compromise. My two in-law old ladies did no such thing. Raise your voice “like a fishwife?” Dear me, no. They merely collapsed.

From a gardener’s point of view, they were like certain plants that seem tender, that positively wilt when neglected, but then revive astonishingly when watered (or moved to another spot). The Sanseviera, my garden book informs me, “cannot stand cold tap water,” but requires a tepid drink that should be promptly drained from the standing saucer after 15 minutes! The Dieffenbachia, the same source advises, cannot stand full sunlight or its leaves will brown—reminiscent, to me at least, of gently raised Southern ladies whose complexions need to be protected from the cruel outdoors. Neither plant, of course, can be put outside except in very clement weather.

It’s interesting that mothers-in-law have a reputation that is truly worldwide—mother-in-law jokes range as far as India and China. Some mothers-in-law certainly deserved a bad reputation, refusing to relinquish control of their children. Bona Sforza, mother of Sigismund of Portugal in the 16th century, disliked two daughters-in-law, both of whom died mysteriously shortly after being married! Harry Truman’s mother-in-law reputedly criticized him constantly—even moving into the White House to keep an eye on things when he became president! It can be hard for mothers to accept that their children are grown and have different loyalties.

My mother-in-law had a disconcerting habit of bursting into our bedroom—to, say, ask if her shoes were a good match with her skirt. “Mom is just going to the post office” became an amorous code between the romantic young couple that once we were, involving a race upstairs as the car pulled out of the driveway…

But I didn’t ever try to push her downstairs during our 25 years together, and our children adored her, for she was a wonderfully loving grandmother. I sometimes suspect that my own grandchildren might find my idiosyncrasies more charming than do my children—although we live so far apart (continents) that usually when we get together we all bask in the pleasure of our reunion. I haven’t, please God, yet reached the stage of life when I have to sit by a sunny window and receive careful watering. Like most old people, I hope my wilting stage will be short.

Some cultures, at least in the past, didn’t fool around with wilting. I understand that in the far north, old people were simply put onto an ice floe and pushed gently out into the Arctic. I’m not sure that I would want to put even a houseplant onto an ice floe, would you? The ancient Japanese, a friend tells me, shoved their oldies over a steep cliff. A mercifully quick demise, perhaps, but I am somewhat haunted by the idea of hearing the pushers (the children?) starting out for a sushi lunch as the wind whistles past one‘s ears…

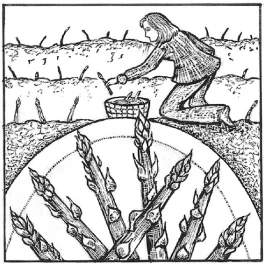

However, as my grandson might say, “It’s not my problem.” Enough! I think it’s about time to inspect my new asparagus patch. Yes, I know it takes several years to establish asparagus. Nevertheless I am intending, in due course, to eat a dish of it, slathered in high-cholesterol butter! But, of course, we can’t tell the future, and dreams aren’t always realized. This, by the way, is purple asparagus (ordered from GREENPRINTS’ very own Territorial Seed Company). I’m really hoping I will get that plateful because purple asparagus is something I’ve never tasted. They say it is “high in anthocyanins,” which surely must be something that the senior frame requires? Best of all, the asparagus, as well as all those houseplants, will give me plenty to be overprotective of—instead of my children. ❖

Previous

Previous