Read by Matilda Longbottom

You might not think that this is all about gardens. But it is.

Just wait.

The royal “we”—the pronoun that sounded so poncy when Queen Victoria glared frostily down her nose and announced, “We are not amused”—turns out to apply to each and every one of us. You’re a we rather than an I. Every human being is a colony, an unwitting cog in a thriving bacterial ecosystem.

Each of us is toting around up to three pounds (yes, pounds) of bacteria—that is, some 100 trillion bacterial cells, the bulk of those in our guts. In fact, cell for cell, we’re more microbial than human, by a whopping ratio of 10:1. Above and beyond the 23,000 genes we’ve inherited from our moms and dads, we’re also, willy-nilly, carrying some three to four million bacterial genes. Scientists now refer to these collectively as the microbiome.

This sounds creepy, but it’s a good thing. While some bacteria are undeniably nasty, a lot of them are beneficial. In other words, micro-bugs are pretty much like people: most are peaceful, pleasant types, but a pathological few are out-and-out bad guys.

Our gut bacteria aren’t just passive fellow travelers. For one thing, scientists have known for decades that they play a role in digestion. The after-effects of bean-eating, for example—delicately known in the 16th century as “windinesse”—are due to a medley of bean sugars that our own enzymes can’t cope with, but that those of our resident bacteria can, generating in the process an unfortunate excess of bloating gas.

More recent research, however, has shown that our gut bacteria do a lot more for us than embarrassingly break down beans. They provide us with necessary vitamins (notably vitamins B and K); they empower our immune systems; they help battle infections; and they manufacture neurochemicals essential for our mental health and well-being. An estimated 90% of the body’s serotonin—a brain neurotransmitter that mediates everything from mood to memory—is manufactured for us, not by our own cells, but by bacteria in the gut.

The bad news: What with overuse of antibiotics, a sanitized lifestyle, and a diet heavy in highly processed foods, we’ve been steadily doing in our gut bacteria. Scientists now believe that the recent rise in a wide range of ailments, from obesity to allergies, asthma, rheumatoid arthritis, Type I diabetes, multiple sclerosis, irritable bowel syndrome, cirrhosis of the liver, cardiovascular disease, and anxiety attacks—perhaps even autism—may have something to do with the loss of bacteria in our guts.

Bacteria-wise, we’re a lot more boring than we used to be. The bacterial profiles of microbiomes from non-Westernized peoples are markedly different from our own. The microbiomes of people in nonindustrialized countries have a far greater diversity of gut bacteria and include species that are rare or flat-out absent from our own. Ours, the latest research indicates, are impoverished, depleted, and shadows of their former selves.

So what to do about this?

To a certain extent, our microbiome is up to our moms. Bacterial colonization begins at birth, following our unsterile passage through the birth canal. (C-section babies miss out on some of this.) We pick up even more helpful microbes through mother’s milk—which not only feeds the baby, but also contains complex carbohydrates that function as prebiotics, intended to nourish the bugs in the baby’s digestive tract. Generally, by the time kids reach the age of three, following the introduction of solid foods and a lot of crawling around on the floor, their internal bacterial ecosystems are fully established. In fact, kids, at this stage, may be better off than most of us, since usually, by adulthood, we’ve lost the drive to stuff grubby, but bacterially diverse, thumbs and teddy bears into our mouths.

Once you start thinking of yourself as a we, your take on the world changes. After all, you’re not just eating for yourself—you’re eating for a unique-to-you population of thousands of bacteria—and frankly, they’re not into junk food. Recommended for the good of your microbiome is a diet rich in probiotic (microbe-stuffed) fermented foods such as yogurt, sauerkraut, kimchi, and miso soup, and in fiber-rich prebiotic (microbe-feeding) foods, such as whole grains, fruits, and vegetables.

It’s best to back off processed foods, which may feed you, but don’t do diddlysquat for your gut bacteria. In one much-publicized experiment, a college student spent ten days on a dedicated nothing-but-fast-food diet, consisting of fries, burgers, chicken nuggets, and Coca-Cola. He started out with a gut population of 3500 bacterial species; by the end of his fast-food binge, he’d lost a third of these.

Think about it. It’s sort of like starving your pets.

Antibiotics also don’t do much good to the microbiome. While sometimes we need them—and certainly shouldn’t avoid them when necessary—we should be cautious about overusing them. Studies show that the gut microbiome can take up to a year to bounce back after a course of bacteria-blitzing antibiotics.

So what does this all have to do with gardens?

A lot, actually.

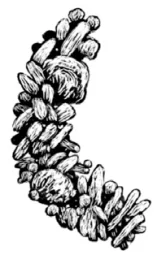

The increasingly feeble Western microbiome, scientists suggest, is a result of our restricted lifestyle: We just no longer spend much time fooling around with dirt. A mere teaspoon of good garden soil contains anywhere from 100 million to one billion bacteria, comprising up to 50,000 different bacterial species. The more we interact with garden dirt, the better our chances of beefing up our internal bacterial ecosystems, and the better off—health-wise—we are.

There are, of course, so many reasons to garden. We garden for pleasure, for exercise, for healthy organic food. We garden to save money.

But, whether we know it or not, we also garden to cultivate our internal bacterial gardens.

And keeping that garden thriving may be more important than we think. ❖

Previous

Previous