The summer I first visited the circa 1795 Massachusetts farm-house that eventually became our home, I noticed a long row of tall plants arching over the fieldstone walls behind the house.

“What is that?” I asked.

“Japanese bamboo,” my elderly friend Elisabeth replied. “It just sprang up out of nowhere. Isn’t it lovely?”

Lacy sprays of creamy, aromatic flowers draped from heart-shaped emerald leaves. In the light breeze, they fluttered as gracefully as butterfly wings.

“It is,” I innocently agreed.

It was not until years later that we learned it had a secret life.

After my husband, Michael, completed clearing decades’ worth of entangled grapevines and poison ivy from hundreds of feet of stone wall along our country road, he turned his attention to the dividing walls that long ago separated the fields of this old dairy farm. The bamboo was now growing in 20-foot-wide bands along several hundred feet of walls. One spring weekend, Michael removed the old, dried canes with a machete, then mowed the new growth.

Rain and a busy schedule resulted in a work delay of several weeks. By that time, new bamboo had risen over two feet high.

“Come look at this,” Michael called. Silently, we beheld our vigorous new crop.

“What is this stuff?” he asked.

“I have no idea,” I replied. “I wish our veggies grew this well.” “Where did it come from? Did Elisabeth plant it?”

“She said it appeared out of nowhere,” I replied.

A quick check on the Internet revealed that the lovely invader had been traveling under an alias. It was not a bamboo. Rather, it was Polygonum cuspidatum, a.k.a. Japanese knotweed.

“Great!” Michael said. “Now that we know what it is, let’s find out how to get rid of it.”

I kept reading. “It says here that it’s really invasive and incredibly hard to eliminate.”

“Remember the poison ivy? I can get rid of anything.”

His confidence was justified. Dressed in roomy, long-sleeved shirt and pants from the Salvation Army, workgloves and tough old boots, Michael had chopped, dug, sprayed, and stripped poison ivy and grapevines over 15 feet tall from stone walls that had long since forgotten the light of day. Ten feet at a time. Then he rebuilt the walls. It took him from early spring through late autumn.

I kept reading: “‘Japanese knotweed spreads by rhizomes underground and the more you pull it out, the more it grows. Extremely difficult and time-consuming to eradicate once it is established. Even when visible parts of the plant are cut away, rhizomes sustain it—three feet underground or under asphalt.’“

“Just skip to the getting rid of it part,” he said.

“‘Thoroughly digging out roots and stems takes years to succeed, if it ever does,’“ I continued. “‘If even a tiny speck of stem remains, the plant will regenerate.’“

“Try another article. One with results,” Michael said.

“Hmmm. Here’s one. It suggest cutting the plants down to about six inches and then squirting poison into each stem.” I paused. “We must have 100,000 stems!”

“Next,” he said.

“The guys from the tree service are coming in a few days to do some pruning,” I said. “Let’s ask them.”

We did. “Can I get rid of it? Sure I can,” the arborist said. “But I’d have to get a backhoe in here to dig it out. And then use so much poison throughout the soil to kill off rhizomes that you’d never grow anything here again.”

“Time to talk to Jim,” Michael said.

Jim was a self-taught master of machine repair and land management. He lived on a 70-acre parcel deep in the woods.

“Smother it,” Jim advised us. “That’s the only way. Have you checked out laying down black plastic? Although I use old carpeting myself,” he added, stroking his grizzled chin. “It’s heavier. Once you get it under control, keep mowing anything that crops up right away. Takes a while,” he added laconically.

Back home, the Internet confirmed Jim’s backwoods wisdom. I told Michael, “It says here that you should mow it down, cover it in black plastic extending seven feet beyond the growth perimeter, weight it down with stones, and—OMG!—because it will grow even under the plastic, we should stomp it down when it does!”

Michael nodded. “Stones, we’ve got. Stomping, we can do.”

“Then after several months, remove the plastic, dig up the roots—they grow down to ten feet!—and mow intensively. For five years. And check up to 20 feet away in every direction for new sprouts.” I glanced at Michael. He was rubbing his hands together.

“You look eager to jump into the ring,” I said.

“Let the games begin!” he replied.

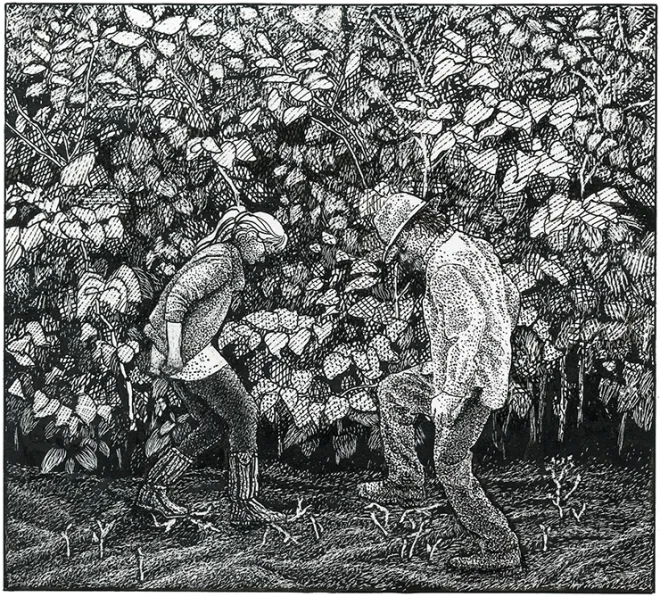

Round One of Man vs. Knotweed began in late summer. Targeting a 20’ x 20’ section, Michael swung his machete like a grim reaper, clearing and then mowing the area. He covered it with black plastic and discarded rugs and weighted it with strategically placed stones. I broke up and bagged the stalks for burning.

But the knotweed threw a few punches of its own. Encouraged by summer’s heat, some of it shot straight up through the plastic, splitting it cleanly. Even less vigorous growth lifted the plastic off the ground. Small black tents appeared everywhere.

“Now what?” I asked.

“Now we stomp,” he directed.

Round Two, stomping, lasted for weeks. “This is therapeutic!” I said as we crushed protruding stems beneath our work boots. “Helps relieve stress!”

Our nearest neighbor, Bob, peered out at us from behind his curtain windows. I waved gaily and kept stomping.

Stomping persisted until a hard frost wilted any remaining stems. Then Michael lifted the plastic, removed the weakened weeds, recovered the stripped ground with two layers of over-lapped plastic, and replaced the stones.

But beneath plastic and winter snow, the knotweed festered. Come spring, when the plastic was peeled back, long, spindly white shoots webbed the soil’s surface.

And so Round Three began by pulling shoots. Each shoot connected to twisting, sprawling orange roots, extending up to 20 feet long and several feet deep, randomly punctuated by bulbous, potato-sized rhizomes.

We got nowhere fast.

“This will take forever,” Michael said. “Let’s try something else.”

He sank his shovel horizontally into the ground, pulling out roots as he worked. He tunneled and yanked his way across the plot, rapidly excavating yard after yard of ropelike roots before recovering the area with plastic. Working side-by-side, we contested for the longest continuous root (over 25 feet) and biggest bulb (about the size of a softball). Once I excavated a perfect knotweed necklace—a 20-inch stem punctuated at regular intervals with almond-sized rhizome “jewels,” which I displayed in the kitchen until it rotted and fell apart.

By repeating this one-two punch throughout our second summer, Michael was able to heavily seed grass by Labor Day. Innocent sprouts appearing in the new grass were met with no mercy. Before frost, he established a thick, velvety grass carpet.

Finally, a victory. Of sorts. Forty square feet reclaimed. About 4,000 more to go.

That summer, Michael began an all-out assault, working several plots at once. Neighbor Bob finally wandered over and was exposed to an impassioned lecture about organic invasive plant control. Bob quickly retreated and now barely responds to our ongoing stomps, root wrangling, and (“No mercy!”) shouts.

After three years of intensive management, Michael has re-claimed nearly half the knotweed-infested area. Keeping this invasive opponent at bay will require eternal vigilance. And everyone who visits our home gets to hear our story. Many are puzzled.

“But it’s so pretty! So graceful!” They say.

Michael, a mischievous smile creasing his face, is quick to agree. “Since you like it so much,” he says, “I’ll get my shovel and dig you out some.”

So far, no one has taken him up on it. ❖

Previous

Previous