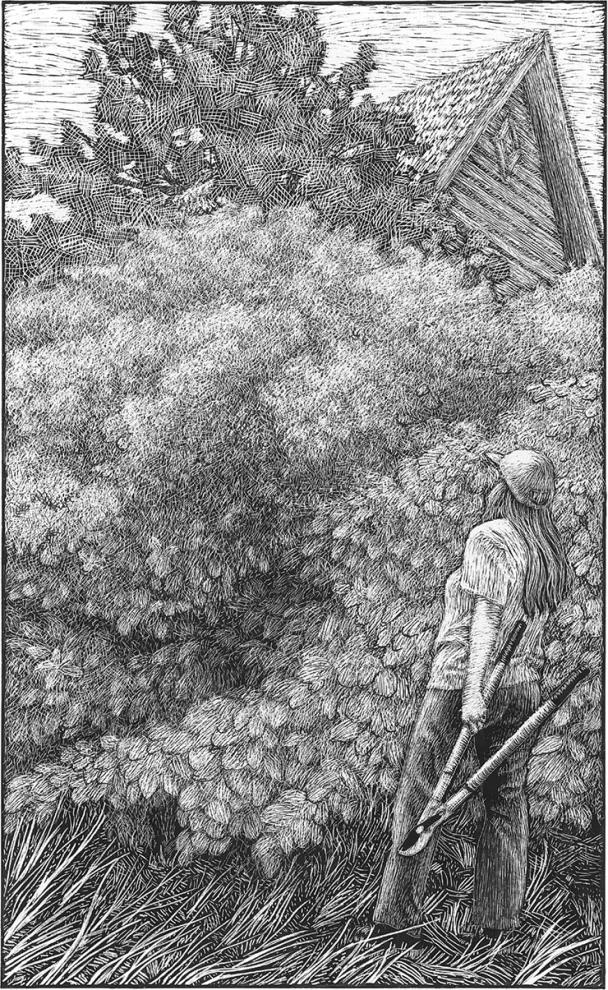

Pruners in hand, I stood below the massive holly tree and stared up at the mishmash of green berries and pointy glossy leaves shooting from the thick, vertical canes of the dreaded Himalayan blackberry plant.

At every edge of every property in the Pacific Northwest, the Himalayan blackberry threatens to Consume All Things. Removing blackberries is an ongoing task for every landowner here. The methods may vary—spraying, digging, mowing—but if neglected, blackberries spread by self-rooted branches or bird-dropped seeds and expand each year, throwing out new canes that reach 15 feet or longer and form a thorny, impenetrable, monstrous mass of vegetation. The canes will even latch onto buildings or other trees. All good property owners know that constant vigilance is a must if you don’t want sheds and shrubs to disappear.

But there are seasons of life when one kind of important work gets overshadowed by another. In our case, it was the birth of our two children that distracted my husband and me from the canes on our farm homestead. What were a few blackberry shoots when my baby was colicky and needed me to soothe her cries? How could I care about the ground behind our garden shed when my son wanted me to read to him about dinosaurs? What was blackberry removal compared to the highs and lows of early parenthood?

Then one day when the children were finally old enough to play without constant supervision, I looked out our kitchen window at our buildings and trees and really saw what was happening. Where once I could see a shed wall, the trunk of a cherry tree, and two giant holly trees, I now saw rough outlines of their shapes under the indistinct darkness of blackberry canes.

Enough. It was a sunny weekend day. I had time. I was going to take care of this mess.

I pulled out my tools and set our two children in their sand pit with plastic dinosaurs and shovels. “Mama has an important job to do,” I told them. “Please, please play well.”

Then I surveyed the situation. I started first with a mower-style brush cutter. The canes were too tall to drive the mower in directly, so I used all of my strength to push the handle down so that its front end tilted up. I then brought it down over and over again on the canes, starting at the edges and working my way in. After several years of baby talk and lullabies, the cutter’s roar was surprisingly welcome to my ears. It was the sound of Getting Things Done on our homestead. I marveled at the finely chopped plant matter left in its wake.

Once I mowed down what canes I could, I went back to the kids. “You still doing OK?” I asked. They seemed to be losing interest in sand play, so I pulled out raisins and cashews for a snack and hoped that’d give me enough time to tackle the next part of my task.

I couldn’t use the brush cutter up close to our shed or trees, so I donned leather gloves and picked up my pruning loppers. Which is how I found myself underneath our holly tree, where canes grew high into the branch scaffold above.

I reached in and cut a cane as close as I could to the ground. Then I grabbed its base firmly and pulled the entire cane out of the brambly mess and dragged it to a burn pile. The canes just kept coming and coming out of the tree, from places I couldn’t even see from below. I felt like a magician pulling a cute rabbit—correction: monstrous thorny snake—out of a hat. Some canes were as thick as my big toe and 20 feet or longer by the time I pulled them out.

Each time I tugged hard on a cane, the entire dark holly would lean toward me—and then snap back when the cane finally came loose. With each snap, berries, twigs, and leaves got caught in my hair and littered the ground.

My children were now playing with the garden hose. I kept one eye on them while repeating my rhythmic task: cut, grab, pull, pull, puuuuulllll—release. Slowly, I started seeing more holly and less blackberry. Progress! I was sweaty, covered in plant matter, but happy with my accomplishments.

And then I caught a glimpse of something different falling—followed by a tiny “Squeak!” The sound was so high-pitched that at first I wasn’t sure I’d heard anything. I kept cutting and pulling and soon, out of the corner of my eye, I saw another small object fall—something light-colored and round. I heard “Squeak!” again. More pulling, more shaking, more falling—and more squeaking!

Finally, I stopped and examined the dark ground at the holly’s trunk. I crouched low, followed the tiny cries, and sifted fallen leaves until I found them: five pink, newborn baby mice. Eyes still closed, they were mewing and pawing at the air. My pulling had shaken them out of their nest in the tree! Now they were on the ground, alive—and helpless.

I sat back on my heels and listened to the contrast between their tiny distress calls and the happy play noises coming from my children behind me.

What had I done? After years of lovingly caring for my own soft pink babies, I might have just destroyed another mother’s infant young. What could I do? What should I do? I don’t like mice when they are in our farmhouse, but could I fault them for building a nest in our tree?

I sat there, stalled in my work, pondering the lines between pest and neighbor on our farm. Some life we obviously welcome; some we don’t. Red-tailed hawks soaring overhead? Welcome. Native ash trees along our creek? Welcome. Blackberries? Definitely unwelcome. Mice in the house? Unwelcome!

But what about mice in our holly tree?

Then I saw a brown blur of movement racing down the holly trunk. A mouse. Could it be their mother, coming for them?

It was. I watched in awe as she picked up a baby mouse with her mouth and climbed the tree trunk into the dark above. As I sat there, she came back for each baby, carrying them one by one to the safety of their nest. Relief flooded through me. I realized that I wanted mama and her babies to stay—and to feel welcome.

“Good job, Mama Mouse,” I whispered to her when she scampered up with the last one.

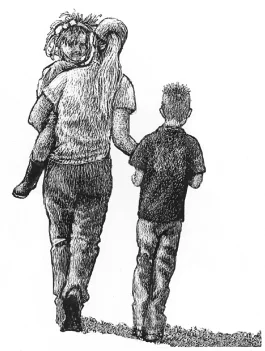

As if on cue, my own babies came over and started pulling at my shirt, ready for their mama to pay attention to them.

I looked contentedly at the pile of blackberry canes stacked for burning. I’d come back and finish the job another day: living here requires taking care of blackberries so there’s room for garden sheds and holly trees.

And, apparently, room for mouse nests, too.

But, for now, my work was needed elsewhere. I pulled off my leather gloves and took my children’s soft hands in mine. Then we headed back to our farm nest. ❖

Previous

Previous