Having arrived in the world of horticulture by a somewhat circuitous route, I’m still thrilled, three years later, to have swapped stifling bureaucracy for the great outdoors—well, for Ardagh Eco-Gardens, a 2.5-acre plot in the Irish Midlands. Now I split my time between working in my and my husband’s garden, communing with the writing muse, and pursuing studies in horticulture. Though it can be difficult to drag myself away from Ardagh, each Wednesday I do just that to spend time in the ultimate inspirational garden, the Botanic Gardens in Glasnevin, Dublin. It’s 300 kilometers round trip from my home in Longford to Dublin and requires an early start. But being able to study in the Botanic Gardens brings its own rewards.

Horticulture study covers a broad range of subjects. I unexpectedly fell in love with one in particular—a module on plant identification. Having never studied Latin at school, I was captivated when I started to grasp its significance for helping a person choose plants. If, like me, you have ever bought plants on a whim without first looking at the name on the label or considering the suitability of your soil type only to watch them wither and die (and let’s face it, who hasn’t?), you will come to appreciate how understanding the name of a plant can save you a lot of subsequent disappointment. This is a vernacular worth delving into.

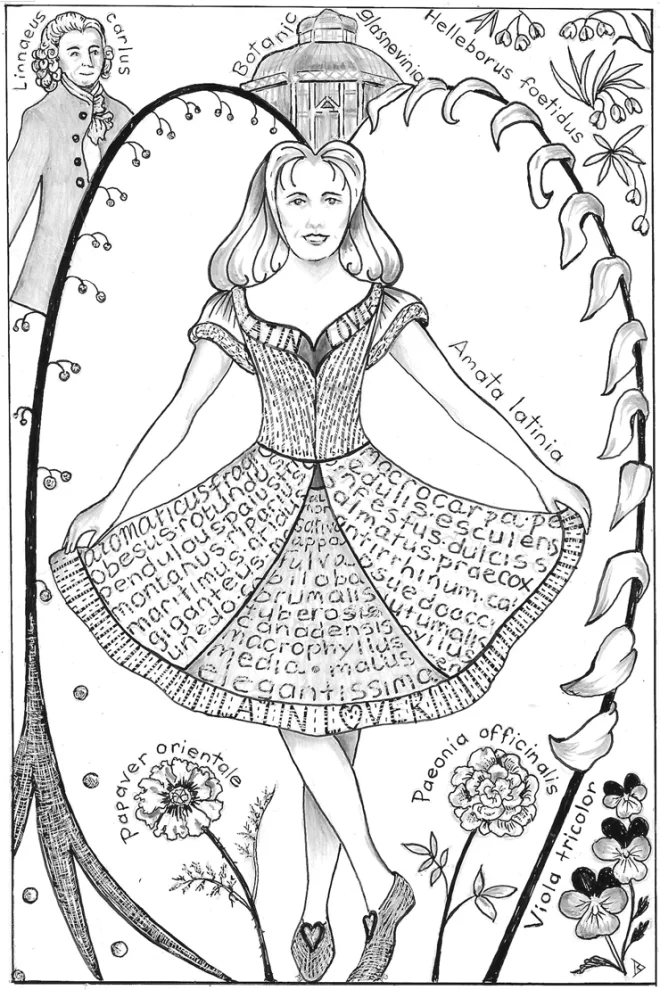

So, what do you need to know? First, understand that the binomial classification system is a universal tool used by gardeners to group plants according to their botanical similarities. This system was developed by the 18th-century Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus and is still used by most plant people throughout the world. Although primarily in Latin, it incorporates occasional Greek because the first plant identification and naming work was done in ancient Greek. The binomial system confers a surname, the genus, and a first, species, name on each plant in that order. Sometimes a pronunciation can seem daunting, but don’t let fear of embarrassment deter you. Just say it with confidence. You only need to tune into the array of gardening programs in different countries to hear the wide variation in pronunciations.

I became convinced of the beauty and usefulness of Latin plant names when I realized that a lot of information about a plant is contained within the name itself. This was something of a turning point for me: I used to be content if I could recall the common name of the plant. Truth be told, in a case of inverted snobbery, I considered the use of Latin names as something of an affectation, so I missed out on all the useful information that botanical Latin bestows on gardeners. Some is reasonably self-evident, for example, aromatic or fragrans, even obesus, rotundatus, pendulous, or aquaticus need little translation. Others are less obvious but no less useful, such as palustris—grown in marshes; montanus—of the mountains; and riparius—of banks or rivers. Following that line of thought, it should come as no surprise to you that a maritimus will do best by the sea and that an aridus enjoys a well-drained soil. If, like mine, your garden is wet and marshy, then anything with palustris in its name will reward you by thriving there.

Another example: if you have only a small garden, a plant name containing giganteus, grandi– or macro– should be a red flag. Indeed, had my poor father known the small bareroot Cupressus macrocarpa whips he innocently planted by the public roadway in the 1970s would grow over 30 meters tall, dwarfing all around them, he might have saved a fortune in tree surgeon fees decades later!

If growing edible plants is your thing, know that edulis means edible, esculens implies that it is tasty, while dulcis simply means it is sweet. Without any admission of guilt on the part of this author, do be aware that planting the attractive statement tree Arbutus unedo will not provide you with the ingredients for dessert—despite its common name of strawberry bush. Enough said on that!

Having some idea of the shapes of mature plants is hugely valuable when designing a garden. You may have figured out by studying the leaf that a palmatus is palm- or hand-shaped, but did you know that antirrhinum means like a nose, while auriculatas is ear-shaped? Anything with dendatus in its name will be toothed, usually in its leaf outline. If you want something small-leafed, look for a microphyllus. Conversely, seek out a macrophyllus if you want a large-leafed specimen.

Want to ensure color all year around? Know then that praecox means flowers early in Spring, aestivalis in Summer, autumalis Autumn, and brumalis in Winter.

Once you start paying attention to those labels, you will quickly and advantageously learn to avoid plants with infestus in the name—and that the terminalis in a name like Pachysandra terminalis actually means it’s an indefinite spreader! While a small amount of pungens can stoke curiosity, you’d do best to avoid olidus or foetidus—at least in close proximity to your house. If only I’d known this when I planted my lovely dark green Helleborus foetidus beside the back door! A very attractive addition to the garden in Spring, it bestows a stench we try to tolerate when the flowers fade. Other Latin names that have long been adopted into English convey to us that an elegantissima or callistus (“most beautiful”) will grace the garden beautifully, while a mirandus (“to be marvelled at”) will make an extraordinary statement wherever you plant it.

So next time you head off to the garden center, read those labels carefully. It pays untold dividends not to confuse your minimus with your maximus or your olidus with your aromaticus! Better still, take a course in botanical plant identification. You might end up, like me, becoming a secret Latin lover! ❖

Previous

Previous