Read by Matilda Longbottom

The narrator of Wishtree, a new book by Katherine Applegate, is a tree. The tree’s name is Red—it’s a northern red oak, Quercus rubra—and it’s been a neighborhood tree and home to a thriving community of animals for a long, long time. Trees can’t tell jokes, Red explains, but they can certainly tell stories. And, he or she continues, while trees do talk, they don’t do so to just anybody: At heart, they’re introverts, so if rustling leaves are all you hear, don’t be disappointed. Red, however, has a wonderful story to tell, and does—and there’s a happy ending. I love the talking tree. I love this book.

On the other hand, it also left me a guilt-stricken wreck, since I, in my time, have been party to cutting down trees. Worse, it’s hard not to wonder what our trees—right now—are saying about us.

When we first bought our current house—once my granddad’s turkey farm on northern Lake Champlain—it was surrounded by four enormous poplar (here in Vermont, popple) trees. Some years after we moved in, two of these fell down, spectacularly, in a winter storm, taking out electricity to all three permanent residences on our road, a disaster which we will never hear the last of, though it really was not our fault.

The third tree started leaning so alarmingly toward the kitchen that we had it removed too; and the fourth, increasingly hollow and ominously close to the kids’ bedrooms, we subsequently cut down due to fear. Even I, romantic as I can get about trees, could see that—given a good north wind—that poplar could have squashed us all flatter than pancakes.

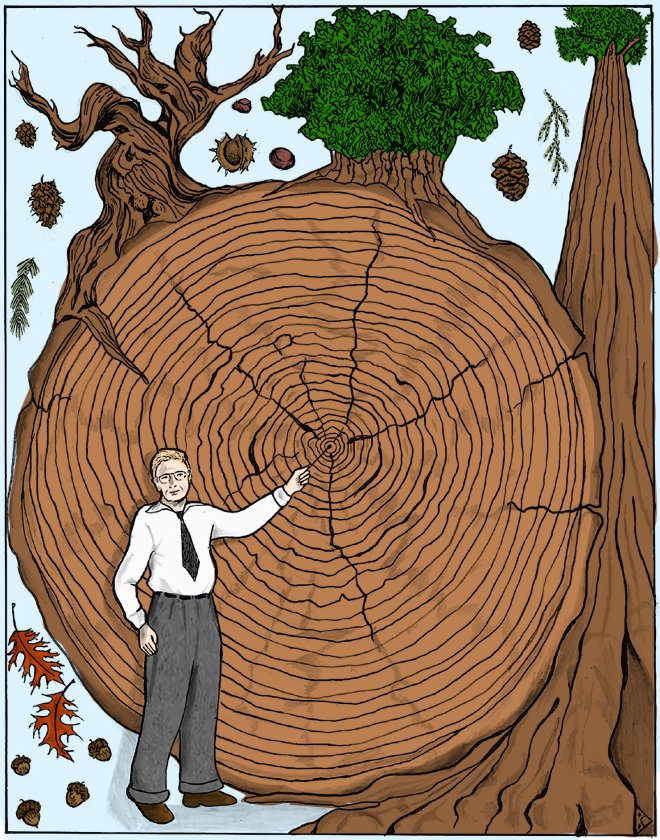

As a family, we were never able to agree exactly how old those poplars were, though counting of rings (multiple times by multiple people) on the left-behind stumps indicated they were pushing 200 years. We all hated to see those trees go. If those trees could talk, they’d have had a lot of stories to tell.

In a sense, of course, all trees do.

Dendrochronology is the science of dating based on tree rings. It was the brainchild of Andrew Douglass—a Vermonter from Windsor—who began his career in the late 19th century as an astronomer under the tutelage of Percival Lowell, who was famed for having imagined he discovered canals on Mars. Douglass split with Lowell over the Martian canals—he perspicaciously said that there weren’t any—but instead went on to discover that there was a correlation between sunspot cycles and the size of tree rings. This was (unlike the canals) the beginning of a far-reaching scientific discipline.

Tree rings—also known as annual growth rings—form just beneath the bark of a growing tree. In the temperate zones, these come in alternating bands of light and dark: The fatter, paler rings represent the rapid growth that takes place each spring and summer; the skinny, darker rings, the pokier growth that occurs in fall.

Slice a tree and its concentric innards are a history of arboreal experience. Tree rings tell us which years were wet and which dry, which hot and which cold, which made for lush growing seasons and which led to belt-tightening misery and struggle. Ice Ages, floods, droughts, volcanic eruptions, and the Industrial Revolution have been faithfully recorded, one ring at a time, by trees. For anything we ever made out of wood, tree rings were there and—with a little calibration—can tell us just when we did it. Using tree ring measurements, archaeologists can date anything from Stone Age campsites to Viking ships, Renaissance paintings, ancient British walkways, colonial cabins, and Native American longhouses.

Trees, unlike us, live a long time. The bristlecone pine, reliably producing a ring a year, can live 4,000 years or more; one of the oldest, nicknamed Methuselah, in the Inyo National Forest in California’s White Mountains, is coming up on its 5,000th birthday. A chestnut tree in Sicily—nicknamed the Tree of One Hundred Horses, since legendarily it managed to shelter a company of 100 knights caught in a thunderstorm—is somewhere upwards of 2,000 years old; and California’s General Sherman sequoia is—at best guess—2,500.

When it comes to memory, we’re not a patch on trees.

On the other hand, dendrochronology takes more than one tree. It’s a group endeavor.

Trees, like people, are quirky; their rings reflect their backgrounds and lifestyles. Just like growing up in a Brooklyn brownstone, on a Montana ranch, or on the banks of a Louisiana bayou lands us with different skill sets (subway smarts, horseback riding, alligator wrestling), cultural biases, and accents, so tree rings reflect whether a given tree was raised beside a stream, on top of a hill, or next to an asphalt plant. When it comes to history, one tree can’t tell it all.

Because of all these individual foibles, tree memory—aka dendrochronology—is collective. It takes a whole bunch of trees together to create a usable sequence of ring patterns, a dendrochronological timeline, a bigger picture. Taken all together, tree rings from bristlecone pines give us an 8,500-year-old history of California. Cooperatively overlapping oaks cover 7,300 years of life in Ireland; and a lot of traumatized trees in Greece give us the scoop on the eruption of Thera in 1628 BCE, a monster volcano on the island of Santorini, that just may have given us the legend of the sunken land of Atlantis. For all of human history, trees were there, and they’ve got history down.

The other thing about trees is that they’re disinterested viewers. Trees have no political agenda. They don’t care if we’re Republicans or Democrats; conservatives or liberals; environmentalists or climate-change deniers; black, white, or otherwise; L, G, B, T, or plain vanilla. They just tell it like it is, year after year. Trees don’t lie.

Which is yet another way in which trees are different from us. Human memory, as a host of studies show, is squishy, if not downright fake. Sometimes we remember things that never happened. Subconsciously, we edit out bits of our past histories that we don’t care for, and disproportionately exaggerate those that we do. We constantly rewrite our own life stories, and we’re big on self-promotional spin. And don’t even get me started on eyewitness testimony. Hardly any of us, it turns out, accurately witness much of anything. Memory-wise, we’re all space cadets. We could do with a few growth rings.

We’ve got oaks and maples in our yard, willows, poplars and pines, a row of cedars, and a box elder tree. Since running into Red, I find myself wishing that they could tell me more about where we’ve been and where we’re going. I’d like to hear their stories.

I wish I could hear more than the rustling of leaves. ❖

Previous

Previous

love this story – I like to write and this is wonderful