Read by Matilda Longbottom

Life used to be easier for gardeners. We didn’t bother with compost. When plants looked pale, the nice man at the hardware store gave us green stuff to put on them. When they got buggy, the same nice man gave us spray and the bugs disappeared. We put chemicals on our closely mowed lawns. We didn’t pretend that weeds were wildflowers. Remember the smell of bonfires in Fall? Politics hadn’t come into the garden, and ecology was something to do with smoking dope and not wearing a bra. Life was easier then.

In those days when we ordered seeds, we just looked for the glossiest packages with the biggest promises. Now of course, gardeners know or ought to know that Ordering Seeds is a Responsibility. Hybrid seeds are a threat to diversity. Nurserymen who sell them are Attempting to Take Over the World.

There has been such a uniform development of hybrids that the plant gene pool is endangered—everyone grows the same hybrids and the old seed strains are fast becoming extinct.

One day all the tomatoes will drop down dead at once because all will be unable to resist the same disease. But wait! This may not happen because we gardeners are cleverly outwitting the corporate mega-garden companies by sowing “heirloom” seeds. Heirloom seeds are those our grandmothers raised. They come true even if they are kept for a year in your bosom. Modern, F1 hybrid seeds don’t come true if they are planted the first day after harvesting. And that’s one reason, we are told, that large nurseries are raising them—so we have to get new seeds every year and keep business going. So, friends, if you can’t get your seeds from somebody’s bosom, for your conscience’s sake, buy heirloom seeds. We ecological gardeners know that.

One year I planted an honorable heirloom, “Alisa Craig” tomatoes. I understood they came from Scotland, probably on the Mayflower, in somebody’s sporran. I was sure they were named after some bonnie Scottish lass. Alisa: I could see her I shawl knotted round her slim waist, eyes the color of hair bells in the brae. She stood outside the croft, silhouetted against the purple heather, rounded arms stretching to hang her father’s kilt on the line to dry. In the distance, the thin sound of the bagpipe pierced the clear air. The wind ruffled her red-gold hair. Ah, Alisa Craig.

Like Alisa, hybridization, or crossbreeding, goes back a ways. Indeed, it’s as old as nature. But for a long time, hybrids were regarded with suspicion. They were considered impure.

Perdita, in A Winter’s Tale, condemned streaked “Gilliflowers” or carnations, as “Nature’s Bastards.” Andrew Marvell wrote in 1681 about “Forbidden mixtures,” and said the double pink was “double as … (man’s) mind.” Perhaps the mistrust of hybrids was partly due to the fact that while it was known plants could change, it was not known how. Marvell thought the plants doubled because “nutriment did change the kind.” Parkinson (on the one hand) said it was “the worke of nature alone” and that “to cause flowers to bee of contrary or different colours or sents, from that they were or would be naturally, are meere fancies of men, without any ground of reason or truth.” Yet (on the other) he still believed that soaking seeds “in the lees of red wine” might make the colors of flowers different.

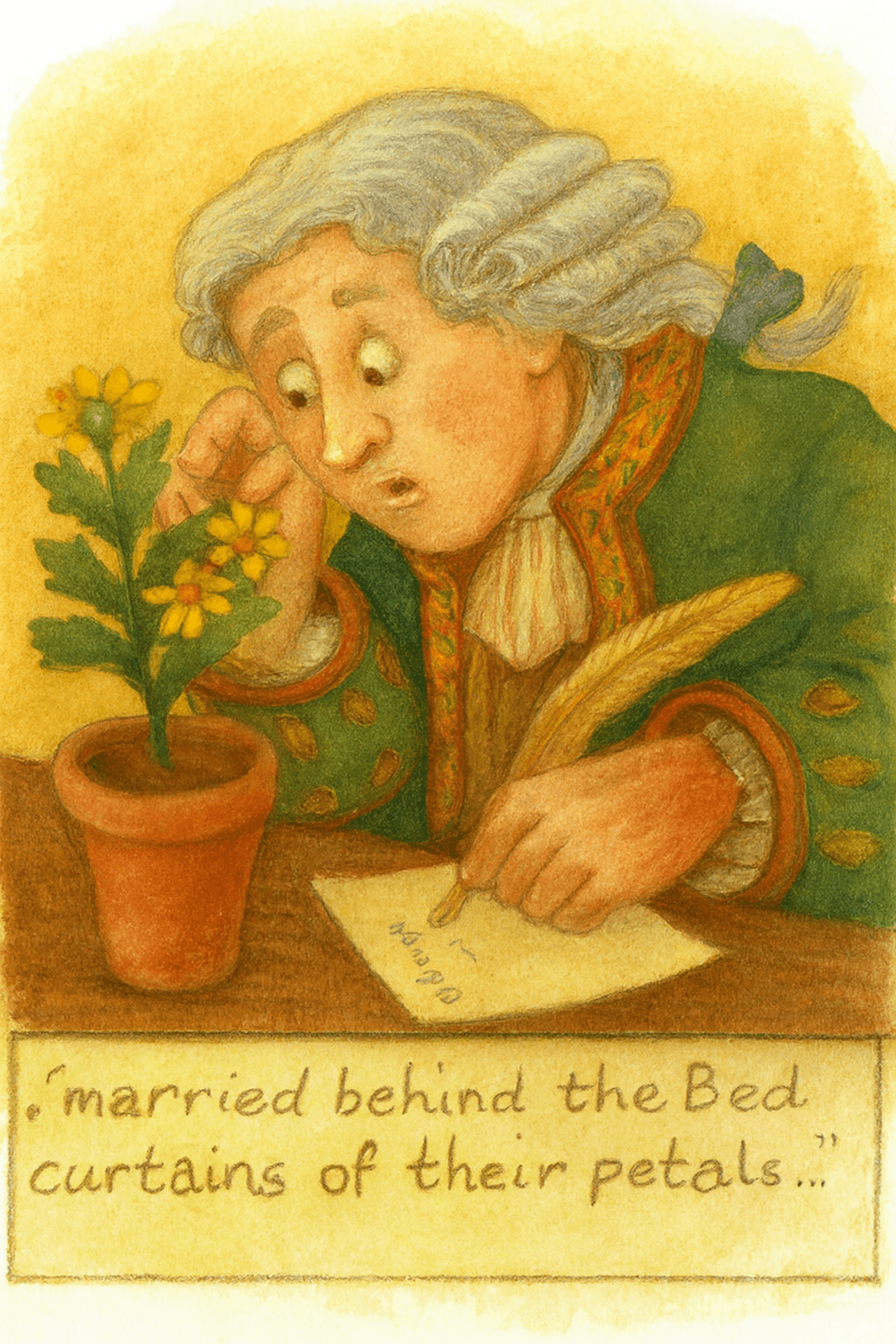

As late as the 1830’s, the gardener and author Jane Loudon wondered if planting a primrose upside-down might change its color. Jane, though, was behind the times, for early in the 18th century, Carl Linnaeus shocked the world by asserting that plants reproduced sexually, that they could be “married” behind the “bed curtains” of their petals and produce offspring. After that, many hybridizing experiments were made, but to confirm the sexual reproduction of plants, not to breed new forms.

The first hybridization attempts to make a new flower form may have been in 1717, when Thomas Fairchild applied the pollen of a carnation to the stigma of a sweet William and produced “Fairchild’s mule.” The result had large red flowers but was sterile and could not be reproduced. However, the practice of deliberate, controlled hybridization had begun.

In 1739, John Bartram wrote to William Byrd: “I have made several successful experiments of joining several species of the same genus whereby I have obtained curious mixed colours in flowers never known before but this requires an accurate observation and judgment to know the precise time when the female organs is disposed to receive the masculine ejection. I hope by these practical observations to open A gate into A very bare field of experimental knowledge which if Judiciously improved may be A Considerable Addition to ye beauty of ye florist gardens … ”

In the 19th century, the gate opened wide—hybridization became a passion. The Victorians made bigger and better plants wherever and whenever they could. Some flowers, like dahlias and chrysanthemums, became monstrous. By the beginning of our century, hybridization science was so respected it was almost taken for granted. Luther Burbank, once told a cactus he was breeding for spinelessness, “You don’t need your defensive thorns, I will protect you.”

Of course, some flowers that we think of as pure are really hybrids. The damask rose was a natural cross between Rosa Phoenicea and Rosa gallica—but we think of it as pure, sweet thing, and it is certainly ancient.

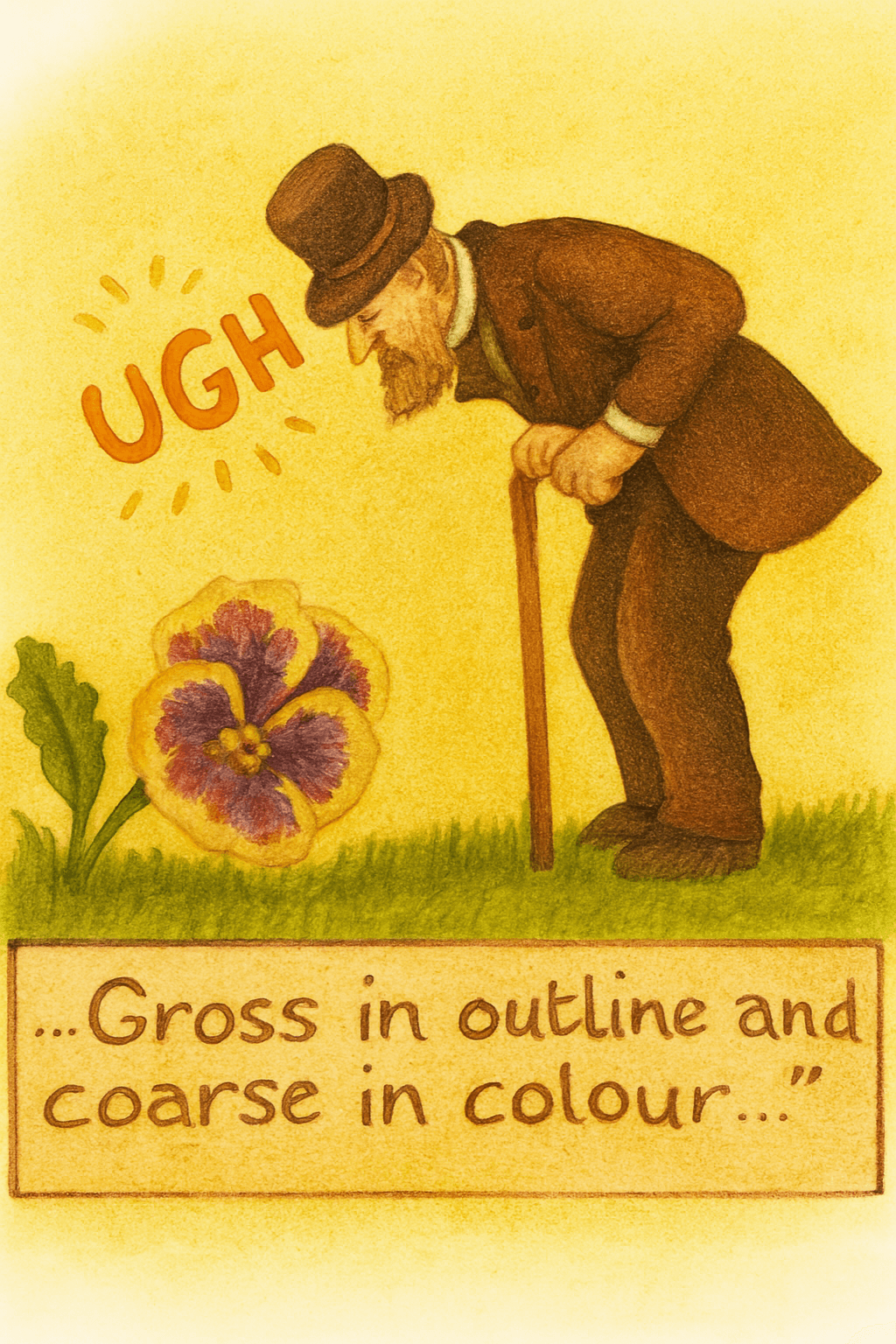

Pansies didn’t even exist until the 19th century. Ruskin said of them: “Quite one of the most lovely things that Heaven has made” (the violet) had been” degraded and distorted by human interference; the swollen varieties of it produced by cultivation being all gross in outline and coarse in colour by comparison.” Today, a hundred years later, we think of pansies as old-fashioned flowers, not as gross, man-made hybrids.

Actually, most of the concern about hybrids today centers not on flowers, but on vegetables. We are told that our food crops are becoming more and more uniform and one day all those uniform corn or tomatoes will be struck by disease and die. It happened in the famous Irish potato famine when Europe’s potatoes were wiped out because they all came from two original kinds which were not resistant to blight.

Only by going to South America and searching for new wild varieties were resistant strains found. Nowadays, unfortunately, “progress” is making fewer wild strains available. But by now you are doubtless wondering what happened to Alisa Craig, whom we left hanging the laundry. There she was, beside the clothesline, her soft bosom outlined against the purple hills, her cheeks flushed from the Summer sun. Then she turned her head and guess who was crouched on a rock beside the clothesline? It was brash Big Boy who had just stepped off a ship from America. He pretended to be gazing at the purple hills behind her, but it was obvious where his eyes were fixed. Hybridization was on his mind.

Was Big Boy being a Bad Boy? Did Early Girl appear—too soon—afterward? I don’t know. I can’t help remembering that although my Alisa Craig tomatoes didn’t exactly get diseased, I, well, must have done something wrong.

Perhaps I should have tried spraying them. But I love the world. I’m not going to spray a tomato, especially one that came over on the Mayflower. I can’t help remembering that croft above the sparkling Hebridean Sea.

Meanwhile, one of my annoying and pedantic Scottish friends informs me that Alisa Craig is a place, not a person. Also, he says, tomatoes do not grow in the Highlands of Scotland. So, who is kidding whom, and what am I to do? Are we then to throw out the hybrids along with the nurserymen that produce them?

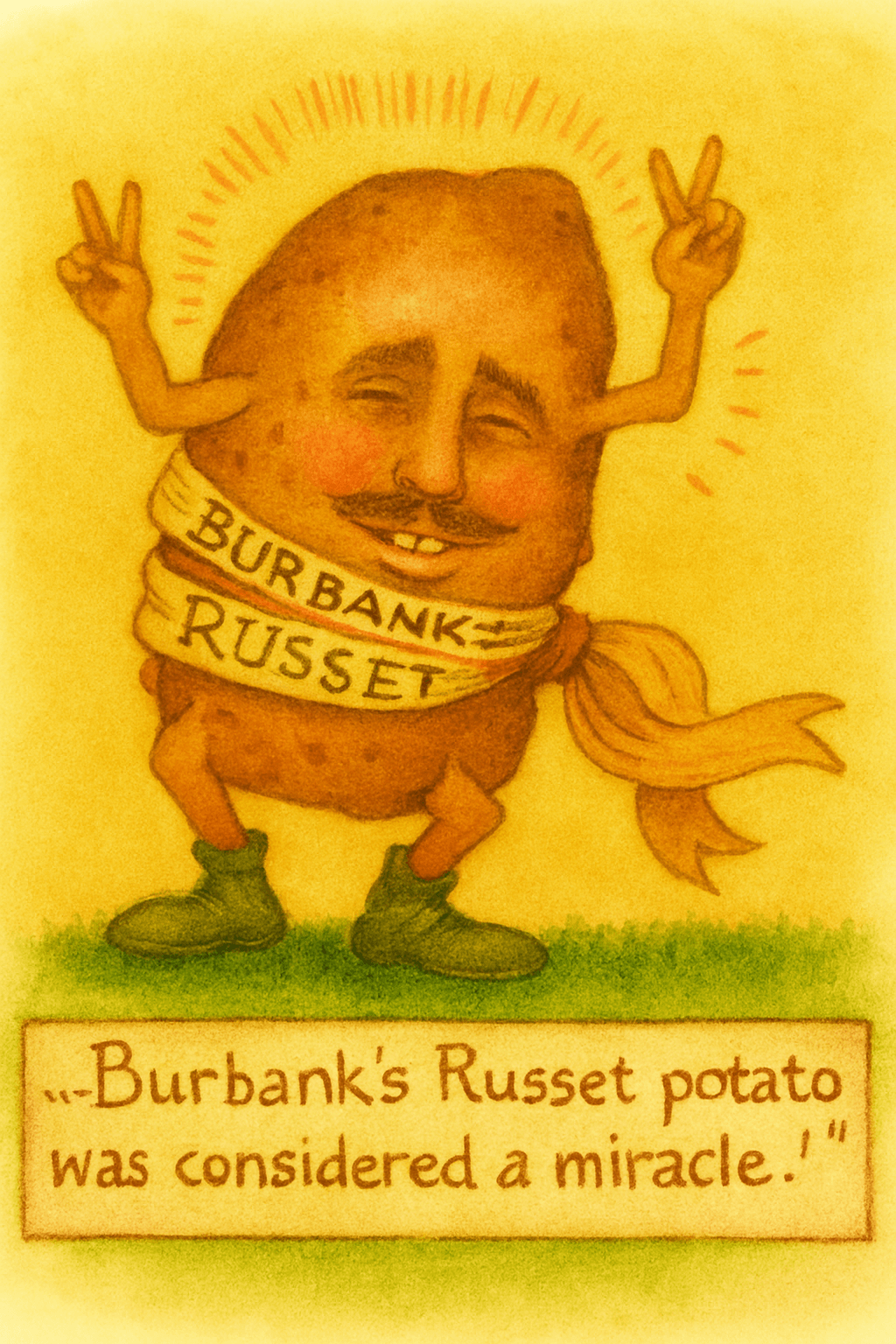

Are we only safe by sticking to purity for its own sake? Is the problem hybridization or how we have used it? After all, you can use a knife to slice your enemy or slice your tomato, and most human inventions have two sides to them. Hybrids have many good qualities. They can be more resistant to disease or drought; they can produce earlier or bumper crops. Luther Burbank’s Russet potato was considered a miracle rather than a threat, a hybrid that helped save the world by its disease resistance and ability to yield heavy crops.

Maybe the issue is this: Does a hybrid increase or decrease diversity and hence our security? Maybe it can be used to add to our storehouse of helpful plants, rather than subtract from it. Too often now, once a crop seems successful, everyone wants to plant it and less diversity results. Sometimes the success has a good reason, but sometimes it is merely for profit.

As for me, what seeds should I order? Maybe a little of each. Maybe it would be fun to order both Alisa Craig and Big Boy. Who knows what I’ll get? A Highland hybrid with the romance of the Old World and robustness of the New? I can’t wait to see what happens in the garden this year… ❖

Previous

Previous

Diana,

You are a most wonderful and intelligent writer with a big brain I can only aspire to having one day. I’d better hurry up though as at age 81 now, I still feel like a fledgling writer! This is a great article and one that has been very enjoyable to me! Thanks so much for your contributions, we love GreenPrints and its writers!