Editor’s Note: This is Diana’s 101st story for GREENPRINTS. Many congratulations, Diana—and thank you for 25 years of wonderful writing!

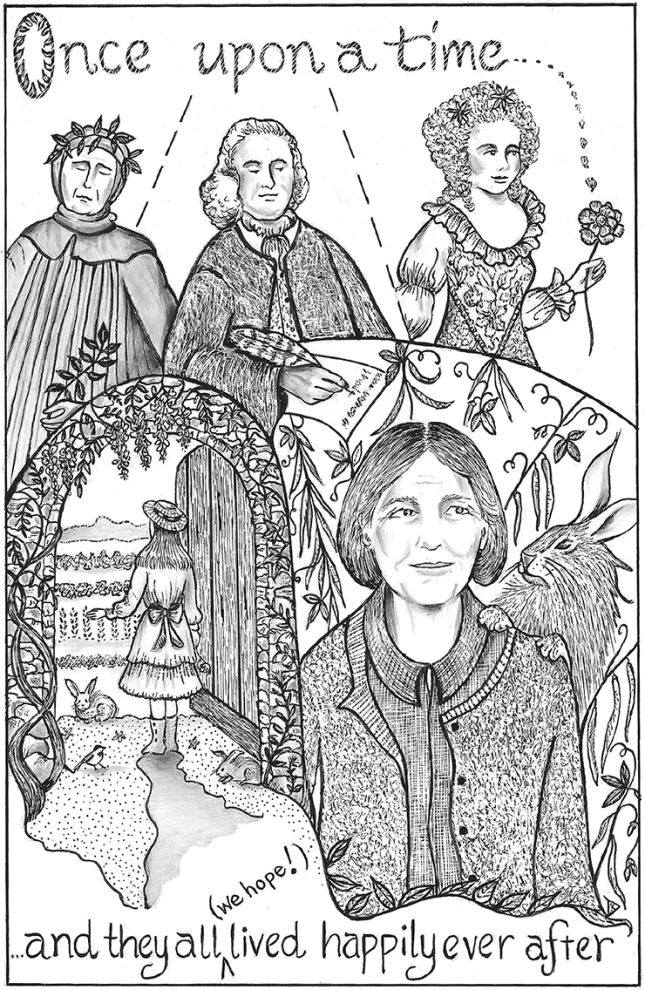

My granddaughter Sophia, aged six, tells me she is writing a book. I am not at liberty to divulge the plot, but she assures me that “You don’t have to worry, Granny, because it has a happy ending.”

Gardeners, probably from prehistory, have looked for happy endings—but we have often been disappointed. Amongst recorded failures is Petrarch, who in the 14th century made several gardens, carefully consulting the moon and stars before planting. Even so, he complained that his spinach, beets, parsley, and fennel failed to come up. He is best remembered for his poetic love for Laura, another man’s wife, but apparently even the laurel tree he planted in her honor did not flourish.

Gardeners, in failure and success, get sustenance from each other. Peter Collinson, an 18th century Quaker who lived in London, corresponded with other gardeners in Britain and also America. “Wee Brothers of the Spade,” he wrote, “find it very necessary to share amongst us the seeds that come annually from Abroad…by this Means our Gar-dens are wonderfully improved in Variety.”

One of his “Brothers” was John Curtis, who lived in Virginia and sent seed to Collinson. In January 1736, Collinson, learning that Curtis had lost his plantings, wrote, “I can truly Sympathize with you nay even feel the concern that you must be under to see your Languishing plants, that all your Pains could not Revive this has happened to Mee Here Once or Twice in my Memory.”

Failure has happened to me at least more than “once or twice,” and I agree with Collinson that “no human skill can describe the passions that attend us.” I confess I can barely write about my lush crop of pole beans covered in blossom and embryonic beans—and nibbled away at the base. There were plenty of succulent weeds around them that the rabbit could have had instead of simply severing the stems…

The garden, in spite of its ups and downs, can and often does provide an escape from the outside world and its troubles. But again, there isn’t always a happy ending. Marie Antoinette, Louis XVI’s unhappy wife, had, during the last few years of her life, a garden farm, or hameau, in a corner of Versailles. Here she and her ladies gardened, milked cows, played games, and took no notice of the menacing development of the French Revolution that inexorably penetrated their carefree world. It is said that the garden was spared, but the 37-year-old queen was guillotined.

Some gardeners say that the act of gardening is more important than the result. We lose ourselves working in the garden and let nature, or God, take care of the rest. It’s a form of worship done, appropriately, mostly on our knees. In The Secret Garden, by Francis Hodgson Burnett (1911), Mary, a spoiled only child, brings a disused garden back to life: “The things that happened in that garden! If you have never had a garden you cannot understand, and if you have had a garden you will know that it would take a whole book to describe all that came to pass there.” This book does have a happy ending—the garden blooms and the children who work there are restored to health and happiness.

A garden is for me like a story, with a beginning, middle, and a planned completion (often not realized!). Each year we begin a new season and follow it through with hopes and failures along the way. Not all cultures garden in this way. Zen gardens, for instance, aim at such timelessness that they don’t always contain growing plants. I confess I am too Western to feel that raked sand tells the same story as a bed of poppies—or even a row of ruined beans! But we all search for happiness, and the path to it is diverse. And not all Japanese gardens are raked sand. Japanese teahouses are approached by intricate paths and stepping stones along which one gradually sheds the cares of the world. Many gardeners make paths that lead to some kind of hidden reward—maybe a pond or a statue. Dull gardens have no surprise rewards.

But no gardens are dull. Gardeners look for and find joy in what others see as the little, common things. Gilbert White, an English parson, never left his village (he got nauseous if he rode a coach), but spent his days keeping track of what might seem to others of little import. His letters, published in 1788, have never been out of print—because it’s impossible not to share his enthusiasm as he notes every day the small excitements in his life. In 1780, he writes “cucumbers swell.” Anyone who has grown cucumbers will note that swell of our pride and anticipation! In 1792, he writes, “Honeysuckles very fragrant, and most beautiful objects!” On June 29, 1783, you can feel his joy when he writes, “My garden is in high beauty, glowing with a variety of solstitial flowers.” We all love our gardens in June…

Sophia is right—I do like a happy ending. Indeed, when a writer leaves me bereft, I am apt to feel cheated. My poor beans are enough sadness in my life, and the greatness of the Bard not withstanding, I confess I would really rather think of Romeo and Juliet waving from a hot air balloon en route to a honeymoon and a happy ending. (All right, purists, I know hot air balloons weren’t around in Shakespeare’s time!) But lovers, writers, and gardeners are best at dreaming, and what’s so great about reading, or watching, everyone die? Aren’t my dear beans enough?

Yes, Sophia, I need a happy ending. So I am already planning my pole-bean strategy for next year. I could try nets? Poison, though tempting, isn’t a very happy ending for a bunny. I’ll have to keep thinking about it.

And you, dear GREENPRINTS readers, keep working on happy endings. Because that’s what gardeners do. ❖

Previous

Previous