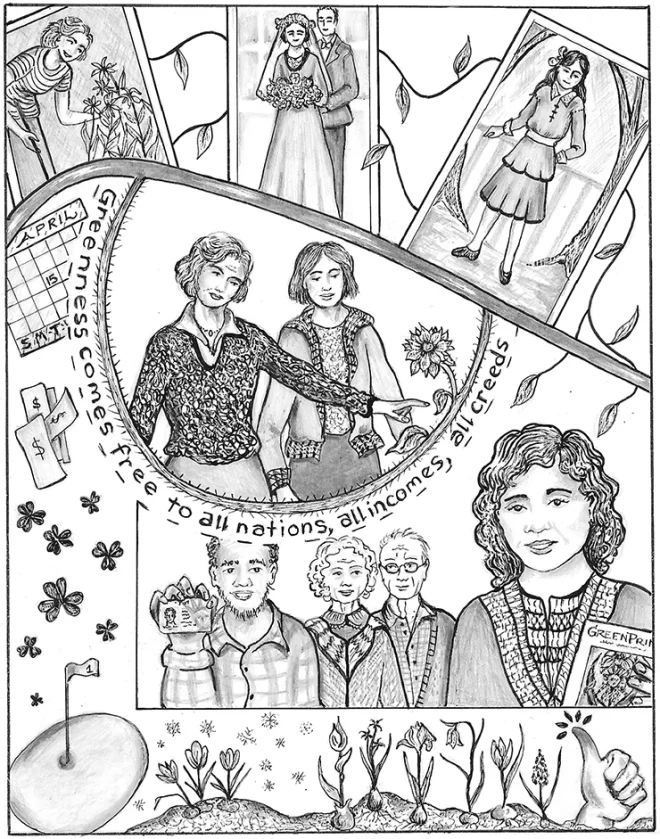

When my mother was young, she always wore green and no other color. She said it made it easier to shop and for people to give her gifts. I suspect, though, it might also have been because, with her slender frame and raven black hair, the color suited her perfectly. In the photo-graphs she seems like a wood nymph or forest fairy.

When my father met her, they became engaged almost at once. He was posted to Africa and wanted her to accompany him there. He (of course) gave her an emerald ring, and her wedding costume (they were married hurriedly) was pale green. It is sup-posed to be unlucky to be married in green and, sadly, in her case it turned out to be so. Later she married again, but by this time she was no longer a green maiden, and I remember her in other colors. Her second ring was not an emerald!

Green has always been the color of youth and renewal: “April prepares her green traffic light and the world thinks Go!” wrote Christopher Morley in 1931. For gardeners, green is what we long for after the seemingly endless days of Winter. In his wonderful 1651 poem, “Thoughts in a Garden,” Andrew Marvel wrote about saturating himself in green: “Annihilating all that’s made/ To a green thought in a green shade.” He flings his spirit up, “casting the body’s vest aside/My soul into the boughs does glide.” Later John Keats scolded a Winter tree: “Too Happy Happy tree,/Thy branches ne’er remember/Their green felicity.”

Whatever poets and gardeners think, green is technically a “secondary” color—a mix of yellow and blue. Secondary? We see it as the color of life! The plants that enable our existence show in their greenness the magical chemistry of chlorophyll which, when there is light, manufactures glucose, forming a vital link to survival. Indeed, the word “chlorophyll” comes from the Greek chloro, “green” and phyll, “leaf.” As anyone with grass stains on clothing knows, the green color in plants is not soluble in water. A “green gown” was once an old way of saying that a woman had “rolled in the grass” (perhaps contributing to a new life!).

“Green” can be applied to giddy youth—not always admiringly. It sometimes means inexperienced and easily fooled. Spring itself sometimes fools us with early greening, followed by a late snowstorm. By then we will have gotten rid of our Christmas greens, which symbolized continued life in darkest Winter, and be looking for a new start. Speaking of starts, immigrants might be waiting for a Green Card to make their new beginnings. On the other hand, seniors hope for a “green old age.”

Sometimes when we don’t get what we want, we are green with envy. We might be coveting somebody’s green bank dollars—which, by the way, were first issued in 1861 to represent a currency of gold and silver.

In our modern world, it is hard to get away from that green: money. Indeed April, the month of verdant Spring (“vert” being another name for “green”) is also the month of taxes. The wonderful thing about gardening is that its greenness comes free to all nations, all incomes, all creeds. It is actually the color of the Muslim religion; it is also the color of the Irish who “wear the green.” It is the color of golf courses and the color of greenbelts that protect cities. And, of course, for gardeners, the color of that well-earned attribute, a “green thumb.” [Editor’s Note: Does something else concerned with gardening have the word “green” in it? Hmmm…]

My mother lived to be very old—and had many ups and downs between her magical youth as the girl in green and her sadness for the death of my sister—from which she never recovered. But she did retain her green thumb. Shortly before she died, she planted bulbs in her garden that flowered after her life was over.

Whenever I would come home, the first thing we always did, before I had even unpacked, was walk around her garden—where she would introduce me to whatever was new. It is someone else’s garden now, but I can still mentally walk around it with her and remember where all the “new” plants were.

And remember her, my mother, in green. ❖

Previous

Previous