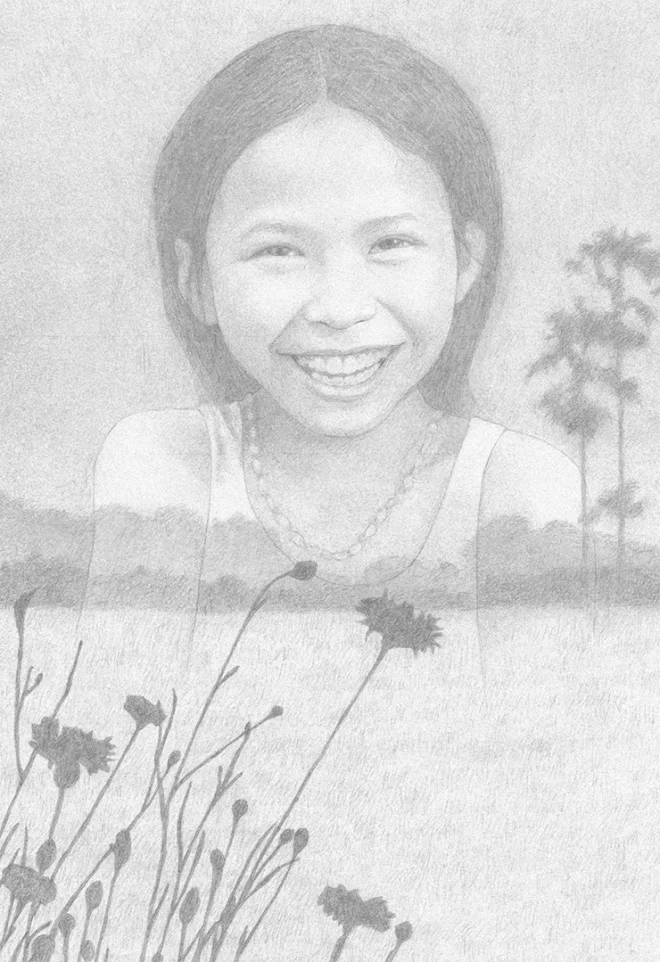

Lea was 9 years old when she was adopted into our family. A mere three days after she came to the United States from Cambodia in November, it snowed. Long Island, New York, isn’t known for its snow, so this was quite a surprise dusting for us natives.

Lea’s life before Long Island had been spent in poverty on a struggling rice farm in Cambodia‘s tropical climate. In Cambodia, one season can bring torrential monsoons that flood crops; the next, famine-causing drought. In the rural farms, proper irrigation, drainage, and sanitation are luxuries few people have access to. “Cambodia very hot,” she would tell me in her beginning English. “No water, no good.”

Throughout her first snowy winter with us, Lea would look at the trees and say, “No leaves. When leaves?”

“In the Spring,” I’d say. “The leaves grow back in the Spring.” “What Spring?”

I tried my best to explain Spring. Trying to explain Spring to a non-English-speaking 9-year-old who has only experienced two seasons—dry and wet—is not easy. So I used what I thought she would understand. Flowers.

“Flowers grow in Spring.”

Lea understood flowers. She loved flowers. We knew that from the minute we met her. When we were in Cambodia, she loved to have us buy her flowers from the scruffy, barefooted children who persistently approached tourists on the street.

“Dollar! Dollar!” the children would say, showcasing rows of rotten black teeth. Their huge black eyes stared up at us, and their threadbare clothes barely hung onto their bodies. The children were so tiny and frail they looked like they were 6, but were probably closer to 10. Their dark hair was streaked blonde, indicating extreme malnourishment. It was next to impossible for my husband and me to turn away from these little ones, so we always bought the flowers. Lea would take the little red flower chains and giggle as she hung them on our driver’s rearview mirror.

I told Lea that it is not as cold in Spring and our yard will have lots of flowers. Yellow flowers. Red flowers. Purple flowers. I told her that she could help me plant them.

“Today?”

“Not today. In the Spring. When it gets warmer.”

“Spring! Bah!” Lea pouted. Patience is not one of her virtues.

W hen I came home in the beginning of May with four flats of impatiens, petunias, and marigolds, along with a hanging fuchsia, she clapped her hands together, smiled, and shrieked, “A lot of flowers!”

She immediately wanted to help plant. So that weekend, we got busy. After a crazy five days of working, driving to soccer practices, cooking, cleaning, etc., it was nice to finally have some quiet one-on-one time with my daughter. As she was digging feverishly, I asked her, “Did you plant rice in Cambodia?” Although I knew that she had, it was difficult for me to picture it. Lea had so quickly adapted to suburban American life. I couldn’t imagine her standing knee-deep in a rural Cambodian rice paddy.

“Yes.”

“How do you plant rice?” I was curious. Although I had seen countless rice farmers when we were in Cambodia, I didn’t actually understand the process. Lea thought a moment. “Mmmm…rice…seed…rice seed.”

“Rice seed, oh, OK.” I should have known I wasn’t going to have an in-depth discussion on rice farming.

“And water,” she added. “Big water.”

“Where did you get the water?” I was trying to initiate a conversation. I wanted her to know that we cared about her life before New York.

She gave me a very perplexed look.

“From a hose?” I said, pointing to ours. I knew full well that she did not have any running water in Cambodia.

Lea laughed and shook her head. “Water come from sky!”

Maybe I was trying too hard. Maybe she just wanted to plant. I backed off from asking questions and let her take the lead.

She led us to silence. And as we quietly planted and watered side by side, I wondered what she was thinking about. Did planting our impatiens remind her of planting rice on her farm? Did watering our marigolds bring back memories of waiting nervously for rain to fall on their bone-dry crops? How easy it was for me to rescue a wilted flower with a quick spray of the hose. How difficult it must’ve been for Lea in Cambodia. No rain meant no food and no income. They were entirely interdependent. The average yearly income for someone in Cambodia is approximately the equivalent of $300. The wage for rural farmers is much less.

When we finished, I spoke. “We’re done. Everything’s watered. Now all we have to do is wait for the sun to do its job.”

“Then they grow big!” Lea said, stretching her arms up high. “Like me!”

I smiled and thought about how she has physically grown so much in the six months she’s been here. She loves to try on the clothes she wore when she first came home and see that they are already too short. She prefers mostly healthy food: rice, her favorite, oranges, melon, lettuce—she can practically eat a whole head in one sitting! It’s the kind of nutrition she did not receive regularly in Cambodia. Nourishment that makes a child grow strong and healthy.

“Yes, just like you,” I said. ❖

Previous

Previous