Read by Matilda Longbottom

According to Kermit the Frog, it’s not easy being green. His sad point was that—being green—you blend, wallflower-like, into the background and everybody passes you by. Green means ignored, neglected, and invisible.

Well, maybe. Personally, I think green is a stand-out. After all, dollar bills, Ireland, and Vermont’s mountains (these last two at least for a couple of months of the year) are all green. So is the Statue of Liberty, which was a bright copper color, shiny as a new penny, when it arrived in New York in 1885—though by 1906, reactions with the New York air had turned it green. The Grinch, Oscar the Grouch, and the Jolly Green Giant are all green. And Napoleon—no slouch at grabbing the limelight—claimed green was his favorite color.

Biochemically, on the other hand, Kermit is right on. From the science end, being green is no walk in the park.

As we were all taught in school, plants have it way up on us because they can make their own food—just by sitting there pointing themselves skyward and using nothing but water, sunshine, and carbon dioxide. They do this with the help of a green pigment called chlorophyll, which is what makes grass, lettuce, spinach, and unripe tomatoes green. The process is called photosynthesis.

Simple, right?

If you ever need to declare a favorite chemical reaction—just in case you’re ever asked in some malevolent board game—make it photosynthesis. It’s the reason we’re all alive.

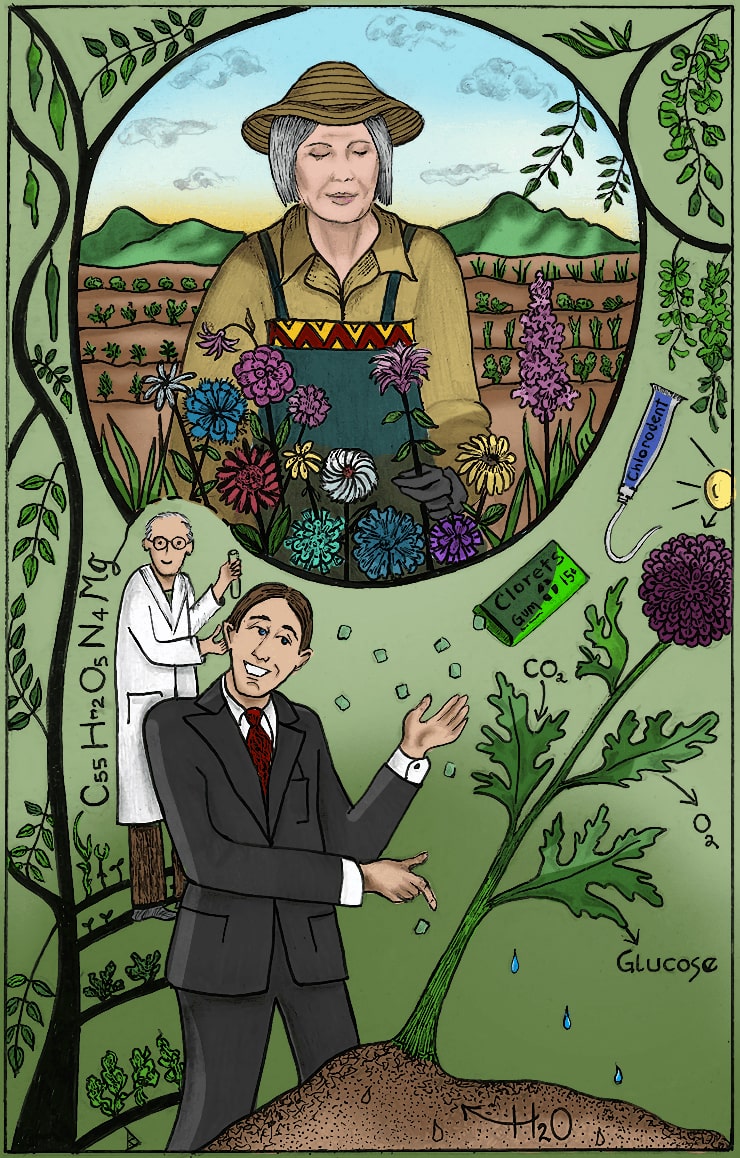

Immediately, however, this gets sticky. First, chlorophyll is complicated. Its basic chemical formula is C55H72O5N4Mg—a grand total of 137 atoms—and it’s not easy to put together. It takes well over a dozen complicated steps and a host of enzymes to synthesize the stuff.

Then, just to make matters worse, there’s not just one chlorophyll—there are six different kinds of chlorophyll, creatively known as a, b, c, d, e, f, and g. And yes, I know: that looks like seven kinds of chlorophyll. The problem is chlorophyll e, which is passionately defended by some scientists as an actual chemical and derided by the rest as a silly experimental goof. We’re not yet committed to chlorophyll e.

Each of these chlorophylls absorbs different wavelengths of light. The two of most interest to gardeners, are chlorophyll a—a flashy bluish-green pigment—and chlorophyll b, a muted, but attractive, olive. A and b are what make our gardens grow.

Despite all it does for us, most of us don’t put a lot of thought into chlorophyll. Its last—and possibly only—leap to fame occurred in the 1940s, when an Irish entrepreneur named O’Neill Ryan set off a chlorophyll craze.

Ryan was piggybacking on research done in the 1930s by Benjamin Gruskin, a respectable scientist at Temple University, who had developed a water-soluble form of chlorophyll that he hoped would be an all-purpose treatment for infections. It wasn’t; it flopped as medicine, to be quickly replaced by the far more effective antibiotics. But Ryan—who took out a use patent on Gruskin’s discovery in 1945—was convinced that chlorophyll was the end-all answer to combatting evil smells.

His first product was a chlorophyll-based toothpaste, marketed by Pepsodent in 1950 as the (bright green) Chlorodent. He followed up with green dog food, chewing gum, deodorant, cigarettes, soap, shampoo, popcorn, diapers, and socks. All sold like hotcakes. Italian fashion designer Elsa Schiaparelli jumped on the bandwagon and invented a chlorophyll-based cologne.

Then —like Godzilla stomping on Bambi—the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announced that scientific experiments had failed to show that chlorophyll had any deodorizing effects whatsoever; and the Journal of the American Medical Association nastily pointed out that goats, which practically live on chlorophyll, smell awful.

Chlorophyll then dropped from the public eye and went back to quietly feeding the planet.

Which brings us to where chlorophyll came from in the first place.

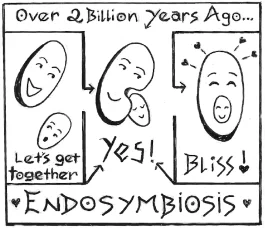

At some point two billion years ago or so, an early cell cozied up to a tiny cyanobacterium—a teeny green bacterial cell stuffed with chlorophyll and capable of photosynthesis—and swallowed it. This ancient get-together—a process now known to biologists as endosymbiosis—turned out to be the greatest win-win in history. The gulped-up cyanobacteria provided their host cells with food and energy; cells, in turn, gave cyanobacteria a safe and comfy place to live. This beautiful friendship—the biological equivalent of that great end scene in Casablanca when Humphrey Bogart and Claude Rains walk off into the mist together—was the kickoff for the evolution of everything from duckweed to oak trees, basil, and beets.

All our gardens came from there.

We’ve got a long history of supportive pairs. Sherlock Holmes, for all his smarts, needed Watson. Calvin needed Hobbes. Batman needed Robin; Abbott would have been a flop without Costello; and who can imagine Bert without Ernie or Bambi without Thumper?

Right now, when our country is so beset by hostility and division, I can’t help thinking about that ancient and serendipitous act of cooperation that made our lives—and our gardens—possible. Together we can do far greater things that we can ever do on our own.

That’s good chemistry. ❖

Previous

Previous