Read by Matilda Longbottom

Don Quixote was just fine until he began reading books.

I think gardening books were what got me. At night I’d pore over lush photographs of gardens from New England and Germany and France. I wanted them all. It was an innocent diversion while we were renting.

When we bought an old house west of Austin, though, I took my gardening books with me. Every evening I’d walk around the yard, making feverish lists of plants in my head. My mind would sweep over the raw Texas countryside, conjuring up rich, lush hillsides of verdant green plants. I didn’t see the cedar trees anymore. In place of these (my version of windmills), I saw flowers.

So I began stacking rocks next to the front porch to make a garden wall. Occasionally, I’d look up from the dirt and stare over the hill. The view didn’t look like the photographs in my magazines, but I found I liked to look at it. It was a stark landscape of a few muted colors: white limestone, wheat-colored grass, and the dark green of cedar and live oak trees. Overhead, vultures circled in a blue sky, and the wind ruffled the tall grass in the distance.

One day, from the side window of the house, we saw something move. “Look,” said my husband, “a deer.” We watched her pick her way past a stand of yucca plants. Her ears twitched, and the white flat of her tail flicked.

We crept onto the porch for a closer look. I could see the deer over the garden I’d planted: ivy, impatiens, four o’clocks, and roses. The pinks and greens looked pretty against the weathered wood of the house, like an old-fashioned English garden. Out near the cedar trees, the deer turned and looked at us with wide brown eyes.

The next morning we opened the door to find that the garden was devastated. The impatiens were eaten; the roses devoured. That pretty little deer had chewed up all my plants.

I kicked a half-eaten rose bush. “So much for English country gardens,” I said.

“There might be more than one deer,” Darrell said. “Their only predators out here are cars.”

I raked up the root balls and threw them onto the compost pile. And I’d thought that deer was so cute. People in Louisiana probably think alligators are cute, too, until one eats their poodle. I needed to look back through my magazines and find a whole new way to garden. I needed something that deer wouldn’t eat.

So the next week I rolled down the driveway with a carful of new plants: marigolds, zinnias, salvia, and poppies. These were deer-resistant plants, and they looked wild and bright against the cedar house, like a Santa Fe courtyard. I tucked the earth around a seedling and stood up, startling four or five deer at the edge of the clearing. Poor things. Maybe it was hard for them to find something to eat.

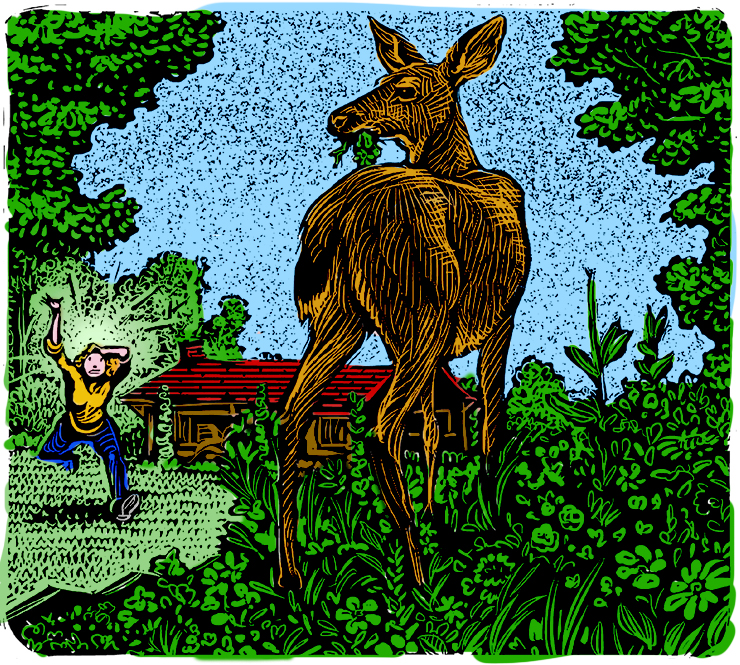

But it wasn’t hard at all. Those deer waded into the garden like folks at a church supper when the prayer meeting lasted too long. So much for Santa Fe courtyards. I needed better defense. I could put up a fence, but an eight-foot barricade around the house would feel less like a home than a prison. Besides, those deer seemed fiendishly clever. They’d probably be able to work the gate.

I looked at my books again and toted home plants that were leathery, pungent, or flat-out poisonous. I planted rosemary, garlic, and mint along one side of the house; datura, iris, and yarrow along the other. I sprinkled all the leaves with cayenne pepper and brushed off my hands. I could feel little beady eyes peering at me from the tree line. I realized it didn’t bother me anymore if the deer were hungry. I poured a little extra pepper on the mulch. But I walked out a week later to find the datura stripped down to its stalk. I looked to see if I could find a deer body stretched out next to it—datura is related to nightshade. The idea of finding a corpse cheered me up. I looked behind me. Seven or eight deer stood near the cedar trees, their heads cocked to one side. They gazed at me attentively, with the same tender interest that vampires probably feel for a Red Cross nurse.

Over the next few months, they consumed the rest of the garden. They ate the flowers off the iris and the yarrow down to the root. The only plant left in the garden was a rosemary bush. It grew two feet wide and waxed luxuriously, in stately privacy. It had plenty of room.

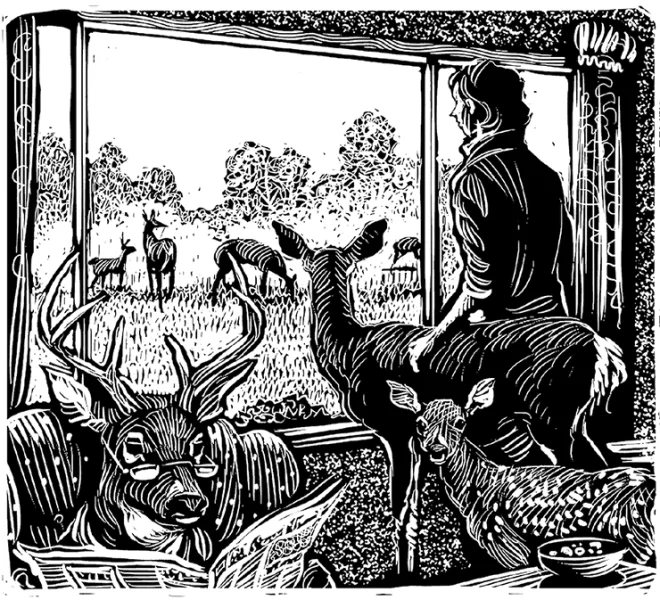

By this time a herd of twelve deer stood out back of the driveway each morning. They’d flick their ears at me cheerfully whenever I opened the front door. In the evenings they’d roam around the yard like cows, huffing at each other, sometimes kicking at a yearling. At night our headlights would pick up the eyes of fawns bedded under the trees. Once a doe parked her baby on the front porch. I knew that one day we’d come home to find them all sitting in the living room reading the paper, smoking cigarettes, and working crossword puzzles.

It had gone too far.

I have always been morally opposed to hunting. When I married my husband, I couldn’t understand how he could shoot animals. They were living beings, a part of the planet, our fellow creatures.

That’s before those creatures ate my flowers. Times had changed. We drove to town and made the ultimate gardening purchase. We bought the final defense in the war against deer, the horticultural equivalent of the A-bomb.

A freezer.

I spent that Fall encouraging my husband to fill up his deer tag. He didn’t like doing this—it was a long way from what he regarded as hunting. I’d look out the window and point at a yearling in the front yard, saying, “Get that one, honey. He ate my marigolds. Shoot him.”

That Winter we put three deer in the freezer. I cooked venison stew, venison chili, and burgers and spaghetti sauce with ground venison. I found that I liked deer meat. It was low fat and easy to use. And it tasted a lot like flowers.

It seemed to work—the deer disappeared from the yard. One day I moved a few plants to the porch and looked out over the clearing. It seemed a little empty with no deer out there.

Then, at the edge of the clearing, I saw something move. Nine or ten deer were moving towards the cedar trees. Most of them were does. I wondered how many were pregnant.

I slumped onto the porch. The deer hadn’t disappeared after all, and they were probably still hungry.

I watched as they picked their way through the Winter grass. Framed against the trees, with the last of the light shining on their coats, they looked delicate and pretty. They looked like they were living where they belonged.

Maybe after a while, I thought, people in Louisiana find that they don’t care about poodles anymore. Perhaps they quit planting Japanese maples and draining the swamps. Maybe they start to walk down to the water every evening, hoping to see alligators slowly rise to the surface of the swamp.

I put my head in my hands. I didn’t know if I’d been creating a garden as much as maintaining a police state. Maybe it was time to accept the landscape the way it really was.

So I gave up. I bought a crateful of rosemary bushes and filled all the gardens with that one kind of plant. Up on the porch, the rosemary smelled rich and oily. The green matched the cedar trees and the leaves on the live oaks. It wasn’t a garden for Santa Fe or England, but a garden for the Texas hill country. It looked like it was growing where it belonged.

After that, we sat on the porch in the evenings, and the deer came every night. Some evenings there would be 14 or 15 of them. They trailed quietly across the clearings, moving slowly. Like walking flowers. ❖

Previous

Previous