I live in prosperous Bucks County, Pennsylvania. There are lovely parks, roads are clean, and every fall a group of businesses and nurseries plant literally thousands of daffodil bulbs for a program called Bucks Beautiful. Then every spring, along roadsides, canal paths, and traffic circles, there are great bursts of golden yellow. And who passes by all this? None other than the horticultural Ebenezer Scrooge, a.k.a. Diana Wells.

I like daffodils and have them in my garden, but (sorry) I think there is such a thing as too many daffodils—at least if we’re talking about the stout, flashy hybrids so popular nowadays. A row of them (and they often seem to be planted in lines) somewhat reminds me of dozens of sunny-side-up eggs on the counter of a busy diner.

Shakespeare wrote movingly about the daffodils that “take/The winds of March with beauty.” Wordsworth, wandering “lonely as a cloud” came upon “a host of golden daffodils,” a sight that ever afterwards lifted his spirits at the memory and remained in his heart that, he wrote, still “dances with the daffodils.”

So what’s the matter with Ebenezer Wells and this attack on one of the great beauties of spring? Well, Shakespeare and Wordsworth weren’t writing about the fat golden flowers of today—but about the little scented daffodils growing wild in the English countryside. Daffodils hybridize easily, and even in Shakespeare’s era a shipment of new hybrids from Constantinople was planted along the Thames embankment—most likely having much the same effect as the Bucks Beautiful plantings. But they wouldn’t yet have spread into the countryside—and the charming wild daffodils still grow in many parts of Britain.

Traditionally, the flowers Persephone was gathering when Hades, king of the underworld, fell for her and abducted her were daffodils—which come back (as she did) every spring. Narcissus, who was exquisitely beautiful (and had spurned the goddess Echo), saw his own image in a pool, leaned over to possess it, and drowned, becoming the lovely flower named for him.

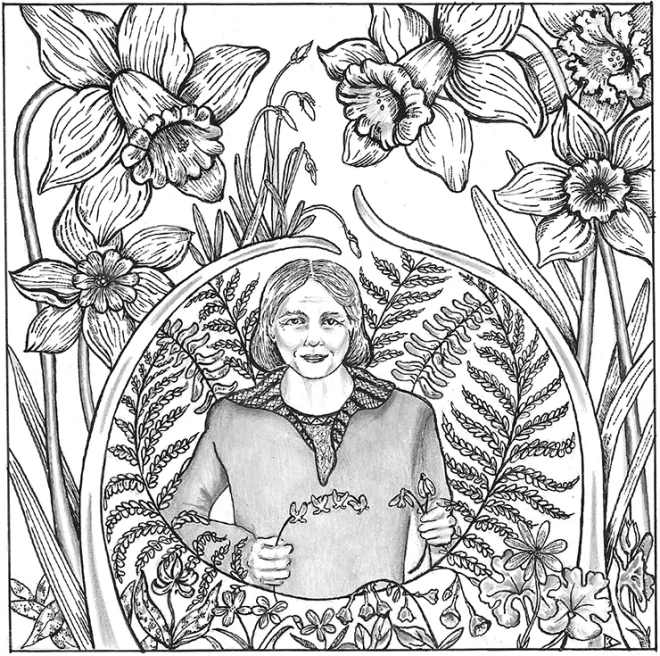

I have daffodils in my garden (even, I confess, a few pink ones!), but my real springtime love is for the little species bulbs, and for the East Coast spring wildflowers that are becoming increasingly rare, often overwhelmed by successful newcomers.

Not all newcomers are harmful, and some are beautiful. Although I find big, flashy daffodils too much, I know that some people love them and that they aren’t really as harmful as the invasive plants that take over whole countries, in spite of our efforts to control them.

Barriers often don’t stop such pests. There’s a famous example of the Oxford ragwort—a pernicious weed found in the Oxford botanical garden (founded in 1621). The garden was divided into plots of various interesting and healing plants and enclosed by a wall. We don’t know who actually introduced the ragwort from Sicily, but we do know that by the end of the 18th century it had escaped over the walls and even used the crevices to reseed itself—and had gone on to colonize the walls of the city itself. In the 1830s, it reached the railway station, where it proceeded to naturalize along the railroad tracks, the fluffy seeds blown along by the trains. By the 1940s, it was widespread all over Britain.

The only way it seems we gardeners can help (apart from spending our whole lives weeding) is by protecting and nurturing the weak and overwhelmed. Flashy daffodils look after themselves—even deer won’t touch them (their sap contains an irritant, calcium oxalate). But the various little wildflowers that grow in the woods around us (what woods are left) could do with our care and protection. I’d like to see more of them along roads and paths. These days I plant as many native and challenged plants as possible—and go easy on imports. My wildflower garden is as staggeringly beautiful as any host of daffodils, even if it doesn’t stop traffic. Virginia bluebells, bloodwort, spring beauties, Dutchman’s breeches, rampion, ferns, trilliums, and dog’s tooth violets are some of the plants early newcomers to America raved about, even when they were introducing favorites from Europe—sometimes with unfortunate consequences. They also sent plants back to Europe—and no one worried much about these exchanges.

We now have a country of mixed flora and fauna—and nothing is going to change that. Yes, huge daffodils are, in my opinion, a bit much, but spring is a short season, and I’m 76 years old. So, instead of grumbling, I should probably, like the poet Herrick (1648), accept all the “Faire daffodils” and “weep to see/You haste away so soone.” I should admire their bright announcement that spring is here—even if some are a bit bold in their statements! ❖

Previous

Previous