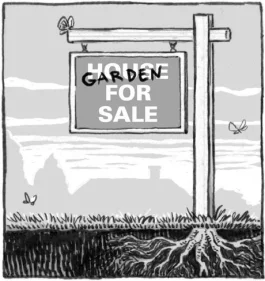

No one should ever sell a house. I’m serious—it’s pure misery and stress, from listing all the way through to closing (Don’t even get me started on buying.)

To avoid these unhappy occurrences, my proposed solution is that a person own one home their entire life. After they pass, their remains should be placed within, and, after the proper rites are with all decorum observed, the whole structure burned to the ground, thus ensuring that no one, not even their heirs, is saddled with the hassle of conducting a real estate transaction.

Take my current predicament, for example. I’m waist deep—and getting deeper every minute—in what used to be a beautiful bed of mixed red and white snapdragons. We’re selling, our buyers want a septic inspection and pumping, and, as it turns out, a few years ago I planted flowers right over the tank.

Not only that, but the bugger is buried deep. My assorted progeny, twins Alena and Thomas, 5, and young Ms. Tara, almost 4, are clustered around the rim of my excavation, and with a little more digging I’ll be standing eye-level with their sneakers.

“Why are we changing gardens?” Thomas asks for the eighteenth time. That’s how my wife Katie and I have explained the concept of moving—a simple (oh, how we lied!) process of changing to a new yard with new flowers, shrubs, and trees.

“Because you guys have gotten so big!” I say, straightening up to give him a gentle poke in the tummy. He grins. “I keep telling your mother, too much good healthy food and they’re gonna keep growing. But she never listens, and now here we are, stuck with three young giants and not enough space for ya!”

“Tell us about the new garden, Papa!” Alena asks (also for the eighteenth time). “There’s a pond, right?”

“Yup,” I grunt, straining to lift a heavy shovelful. “And you guys can fall in whenever you want!”

Alena’s eyes shine. She’s the adventurous one—I knew the idea of a good near-drowning would appeal to her. “What else, Papa?”

“Oh, let’s see. I’m sure there’ll be hornet nests for you guys to step on—that’s always fun! And that really steep hill that runs down to the woods. I imagine you’ll be able fall down that a few times. And of course, there’s the woods themselves—trees to climb and fall out of, sharp sticks to impale yourselves on, you name it! And if all that gets old, shoot, man, this is Maine! You can just wander off and get lost! Sound good?”

Alena spins away in exuberance—I can tell she’s already deliciously imagining dragging herself home at twilight, limping and covered in blood.

But little Tara seems to think I’ve lost focus. “But what about the gardens, Papa?” she says, very earnestly. “Will there be snapgardens?”

“If not, we’ll plant some,” I say. “And ladenver, and lay dillies, and riled woses, too. You and I together, OK?”

Satisfied, she nods and sprints away around the house, her muscular little calves pumping as she hurries to tell her mother, Katie, our future garden plans.

But Thomas remains, squatted down at the edge of the hole, and to my surprise, my young man is not looking pleased. “What’s up, bud?” I ask.

“I don’t want to move!” he says, his face suddenly twisting toward tears. “I like our house and our garden here.”

“Oh, buddy, come here.” I set my shovel aside and pull him to my chest for what must be a very sweaty hug. “It’s gonna be OK. The new house is nice! It’s got the pond and a big yard to play in.”

“But no flowers!” he wails.

“Is that what’s bothering you? We visited early in the Spring. Don’t worry, there’ll be flowers. And next Spring, we’ll plant more. You can have your own bed to take care of, OK?”

This seems to work—he nods, wipes at his eyes.

“Hello, my brave digger men,” says a voice behind me—Katie, Ms. Tara trotting beside her, has come to check on us. “What’s this I hear about our new garden? We’re planting riled woses?”

“And lay dillies, Mom,” Tara explains.

“Only good wose is a riled wose,” I say. “Shall I compare thee to a wose? Woses are wed, but violets are blue, you know.”

“My husband, the widiot,” Katie says, her eyes laughing. “You need any help?”

“No,” I say, “but I think some of us”—I slide my eyes pointedly toward Thomas—“are ready for lunch.”

The whole herd heads to the kitchen for eats, and I return to my digging. My boy’s right—it’s tough to leave your old garden behind. I’ve done a lot of work here—trimming trees and lilacs, leveling, seeding, and watering an addition to the yard, the stone work, the transplanting, the bed-building. It looks nice. It’ll be hard to say goodbye to everything I’ve tended and nurtured.

What’s more, this place brought me a sense of peace and stillness. My children were born here—this is where I finally stopped traveling to places like Pakistan and Kenya for work and settled down, so to speak. So the poppies weren’t the only things putting down roots—my own ties, slow to spread but strong once they got a grip, matured here as well. Moving, for a gardener, is at best an uprooting and a replanting. And everyone who’s ever transplanted a bulb knows it can sometimes take a season or two for the shock to wear off and blooms to come again.

“Can we take my lilac?”

I just about jump out of the hole—Alena has a knack for creeping up on me while I’m ruminating, and now she’s standing right behind me.

“Whew, kiddo!” I say with relief. “You’re a sneaky one, aren’t you? What’s that? No, honey, we can’t take your lilac. It’s too big.” When she found the seedling off the back edge of the yard and we transplanted it, the single stalk was maybe 30 inches high. But that was two years ago. It’s doubled in size twice since then.

She thinks it over. “Will there be lilacs at the new garden?”

“Yes.”

“Good. Well, one of them is mine,” she declares.

And before I can even ask why she wants a lilac, or what she intends to do with it, she’s gone, skipping and singing around to the front yard.

We should all try to be like that, I think, as I lean back to heft another shovelful up and out. Just take whatever the new gives us, accept it, make it ours.

I step on the back of the shovel again, forcing the tip into the sandy dirt at the bottom of my mineshaft, and am rewarded with a dull, metallic tunk. I smile—despite the depth, my excavation came down directly on top of the septic tank’s lid.

Then, realizing I’m smiling, I smile some more—seems like I’m already taking my own advice about acceptance. I’m stressed to the max, abandoning my gardens and destroying my flowers, but I suddenly know everything is going to be OK. Because today, even though I had to sacrifice my snapdragons to access 1,000 gallons of unspeakable goop, I hit right where I was aiming!

I crouch down, using my hands to clear the dirt from the lid. “Alright, goop,” I proclaim—and by “goop” I include the hassle of selling, the hassle of buying, the hassle of packing, the hassle of moving, the hassle of having three small children “help” me through a move, the hassle of leaving my current garden, the hassle of tending a new one, and, yes, the hassle of unearthing this too-deep septic tank—“That’s right, you. You are mine!” ❖

Previous

Previous

Great story! I never want to leave my garden, and totally understand how difficult it must have been for the author and his family.