Read by Matilda Longbottom

My poinsettia is cheerily blooming at last, its tissue-paper white and red contrasting nicely with the green June grass. So what if it’s 80° in the shade, and there are geraniums (also red and white) in full bloom next to it?

I did everything I was supposed to do, including covering it tenderly at dusk with a black cloth, just as I used to cover the cage of the canary which eventually flew away. I even took it out of the spare bedroom when my stepson came for Thanksgiving, thus avoiding his blank look and comment, “What, not turn on the light because of a plant?” That was when I got the first glimmer of realization that, though three of our six sons have grown and left home, I might be, once again, repeating a pattern. “Yes,” the poinsettia seems to say to me, as I potter about in my sun-hat, “I said I’d do it, but later.” I reply that other people’s poinsettias bloom at Christmas. “So what, I’m not other people’s poinsettias!” Pause. I murmur something to the effect that if you were a starving Mexican poinsettia, you’d consider yourself lucky to bloom at Christmas. “So? You want me to go to Mexico?”

As I stagger out to the terrace, carrying the pot, trying not to trip over baseball bats and sneakers, I think of other people’s plants. Peas, for instance. Last year, I decided to do it properly for once. I marked the rows with string and planted them in a straight line. When they all emerged, like dear little compliant soldiers, I gave them nice sturdy wires to climb. I used to go out and stare at the combination, with that wonderful, relaxed feeling I occasionally get when all my children are sitting in church in their best clothes.

Complacency, of course, was rewarded, and when for some reason I omitted going to see them for a few days, it was too late. They had gone under the wire, across the garden, and were firmly entwined with a patch of thick weeds. So I used the wire only for hanging my sweater when I picked peas. For I did pick peas. It wasn’t so much that they weren’t productive, but they were productive—in the most inconvenient way possible. That seems to be how it works when you’re not firm.

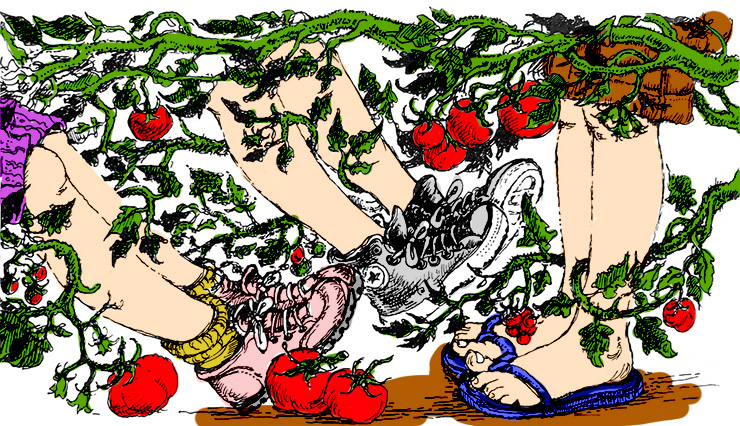

Take the tomatoes. Every year I’ve ended up with a serpentine jungle of great hairy stalks through which I grope and stagger to get the fruit, now and again landing my bare foot in the wrong place, onto a hot, acidy, overripe mess. Yes, I get tomatoes, but they tell you it’s easier than that.

You first decide if you want determinate or indeterminate plants. Of course, you have to be sure that the trays of determinate and indeterminate seeds don‘t get confused. That means labelling them, but what if you find both labels on the floor, part of a five-year-old’s building project? You put them back, and hope.

Later you plant out the tomatoes and find you have far more than will fit into three neat rows. Your friends and neighbors naturally have had the sense to buy their plants from the local nursery, where they are properly labelled and about a foot high. They do not accept the little plastic cups of curling, unnamed orphans you offer them. So, are you to throw them out?

You have nursed them since February, given them the whole of your dining-room table, revived them a couple of times after forgetting to water them, marveled at the way they creep obliquely in the direction of the garden, as if they knew that was their destination. They are rather small, and a little uneven, but they would not be here at all if you had not given them life.

So you do not throw them out. You just plant an extra row or two, thinking one can never really have too many tomatoes, seeing in their tiny, twisted forms row upon gleaming row of bottled spaghetti sauce. By then, of course, determinate and indeterminate have become hopelessly confused, but they do not mind. They grow and flourish, intertwine, romp, and scatter and, suddenly, everywhere you look, there are great hairy vines, stretching like boys’ legs across a TV room where once you walked with ease. I know nothing of determinate and indeterminate, I only know they are determined, and each year I start again.

It reminds me of when our sixth son was born: I knew he would always be beautiful, he would be creative, he would pick up his room, he would never tell me I was wrong, and, laughing, we would walk through straight rows of tomatoes together.

So, once again, my garden is planted in neat rows, and so far the chickens haven’t scratched up the peas. I am trying exotic oriental vegetables this year, perhaps with the vague hope that centuries of a more disciplined culture will keep them in bounds. I picture an enchantingly diminutive garden, but I know in my heart it will not be so. Plants, with that unerring instinct that bends them to the light, know a sucker when they see one. They will not grow in straight rows. They will produce a marvelous crop when I am away on vacation. They will reseed themselves in my rose bed where I am too soft-hearted to pull them up. Once again, I will decide to give the whole thing up. But then, as I pass my poinsettia, I will not pick it up and hurl it into the bushes. Who am I, anyway, to tell it to bloom at Christmas? Sometimes I don’t feel like blooming at Christmas myself. ❖

Previous

Previous