It’s Autumn and “my” bees will be getting ready for cooler weather. Their new “owner” will, no doubt, leave them a good supply of honey to get them through the Winter—and, if they should run out, he may give them a bit of sugar, too. I don’t know who these people are, but I know they love honeybees and will do whatever‘s right.

Coincidences probably happen more often than we are aware. Even so, my episode with the bees was odd. I was serving lunch to a couple of old friends, and the talk turned to bees. The husband, a large, loud man, boomed that the farmers had more or less exterminated honeybees. Had I seen one lately? No? That was because my farmer neighbor had probably killed them all …

After they left, I went upstairs and—yes—the hallway was full of honeybees. A swarm had gone into the siding, and many were coming out through the walls and into the house. There were a lot of them.

I’m not afraid of bees since I kept them for years (see GP No. 18, Summer 1994) and I love honey. But these poor bees came in and then crawled up the windows and walls trying to find their way home. It was clearly not going to work.

I desperately called my son in California. A whiz at the internet, he actually found a beekeeper nearby who specializes in removing bees from house walls. I called him at 5:30 a.m. and he answered—and said he would be along at 10 a.m.

Bees swarm and look for new places to live because their hive, or colony, is thriving so well that it becomes overcrowded. This happens especially in Spring when there is plenty of nectar available. The bees start to raise a new Queen, feeding her the famous Royal Jelly. She grows, and then it is time for the old Queen to leave, which she does, taking a swarm of workers with her.

The swarm hangs from a branch or something like it while the worker bees search for a new home. In this case they chose an uncemented opening between my old stone house and its clapboard stairwell. Voilà—they must have been settling in while my lunch guest right belowwas talking about a lack of honeybees!

At first, I thought we would have to kill them. How could we possibly get them out? I tried “talking” to them—it’s been said they understand us and, indeed, legend says that if there is a death in the family, they must be told. I rang an old brass bell and begged them to leave. “For your own good,” I pleaded. I have to say they took no notice of me at all, even though I thought I was Ms. Bee Lover. They simply buzzed in and out of their crack. Spraying the crack with insect repellant did no good: they simply moved higher up the wall.

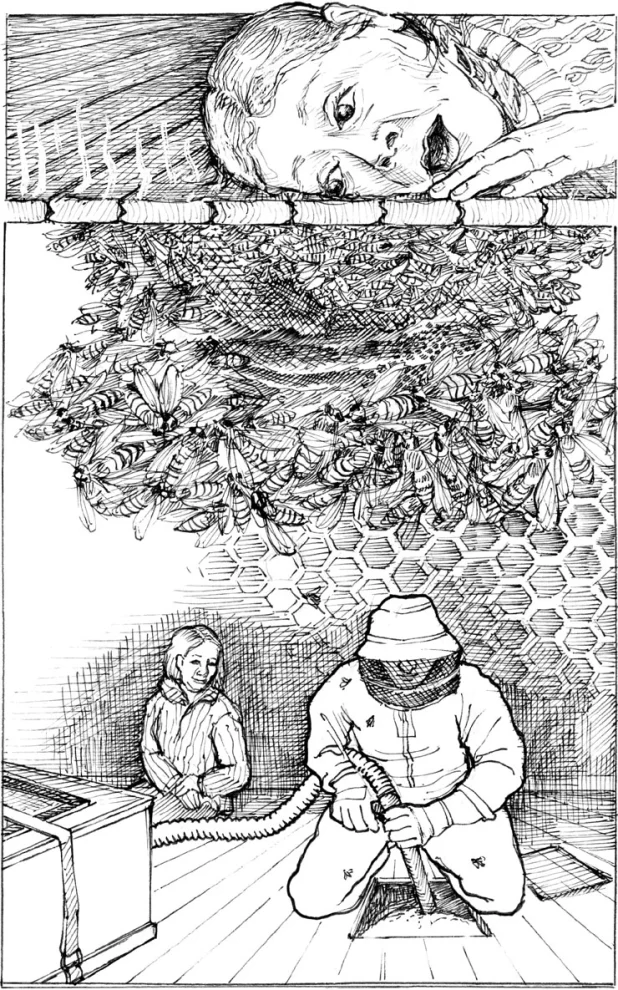

Bob The Bee Man, as I shall call him, was not fazed. He said we should go up to the attic and that we would find them there. I didn’t know how he would know that because, as I pointed out, they were entering the wall at door level. But I dutifully followed him upstairs where he moved a chest of drawers and bade me lie on the floor and put my ear on the boards. I did as he told me, all 81 years of me, and, sure enough, the boards were hot and vibrating.

He knew I had once kept bees and had been acquainted, all those years ago, with some of the local beekeepers. In my day, I was told there was no way you could save a colony that had nested in the walls. Beekeepers sucked them out with a powerful vacuum cleaner that killed them.

Not Bob. First, he drilled a small hole in the floor and put a scope down it. Again he had me on the floor looking through it at the mass of bees in the corner of the beams. That was just what he wanted. He proceeded to cut an eight-inch square in the floor, then he gently pried it out. He said, “They might not like that.” But as I say, I love bees, so I sat next to him while he worked. Again he had me come and look at the golden, buzzing mass he had revealed. They weren’t taking much notice of us, concentrating instead on guarding their Queen, who would have been in the center of the mass.

Without the Queen, a colony will soon die. She is fertilized once by the rare male bees, or drones, in a “nuptial flight.” It’s a one-time stand for the drones who die afterward, and the Queen then spends the rest of her life laying eggs. The worker bees watch the eggs and feed the young that in turn hatch into workers—unless a new Queen is needed and fed accordingly. The workers also watch the temperature of the hive, fanning it with their wings if it gets too hot. In the days when bees were not well understood, it was assumed that the Queen was a King—for how could such an important bee not be male?

Bob was now ready to get the swarm out. He had a special, gentle vacuum (we had to pause while we searched for an electrical outlet and extension cord). Gently, very gently, the bees were sucked into a box, until finally the mass was inside. By then a lot of escapees had plastered themselves on the windows. He sucked them up, too. It all took about two hours, maybe a little longer than it should have because at every stage he had me leave my seat on the stairs and look closely at what he did. Finally, it was time to put in new insulation, close the floor, and take the throbbing box down to his truck. He already had a new beekeeper waiting for them. I hoped they would like their new home. Bees, as “my” swarm demonstrated, are apt to do what they want.

Bob and I parted the best of friends. He said he charged me less than usual, and I was not to tell anyone how much. While I was writing the check, his phone rang. “I’ll be right along,” he said. There was another swarm in someone’s wall. He insisted on sweeping my floor before he left, in spite of my protests.

I then waved goodbye to the box of bees and, Covid or not, gave him a hug. ❖

Previous

Previous