Elizabeth Alexander is a poet and Professor of African-American Studies at Yale University. Her husband, Ficre Ghebreyesus, was a native of Eritrea, Africa who became a refugee, emigrated to Europe then America, and became a gourmet chef and abstract artist. Elizabeth’s 2015 book, The Light of the World, is a memoir of their marriage and her family’s loss after Ficre died suddenly. It is an intense and lyrical tribute to love.

Here are two short excerpts centered on gardening.

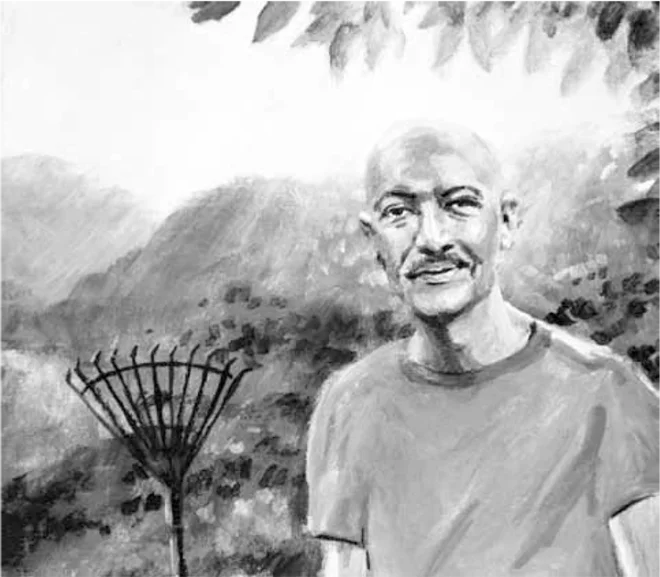

May ninth, one month and five days after he died, he almost comes back. The children and I amble in the garden, enjoying his domain. The boys take turns standing on his top-of-the-world grassy mount. Perhaps four feet at its tallest point, Ficre piled and packed the dirt left from furrowing the garden’s rows. From his mount, he worked and surveyed.

It begins to lightly rain and the boys scurry inside. I can see Ficre plainly atop his hillock. Come on! I say to him from the side door, gesturing towards the house. Come in from the rain. He stays where he stands, his eyes an infinity of sadness. Please, please, come in, I implore. He is outside and we would be inside, not forever but for a long, long time.

I muffle my cries so the children will not hear me, but months later, they will say, Mommy, we always used to hear you weeping in the garden.

The next morning I return to bed in a quiet house after the children leave. I wail like an animal and then I sleep, and Ficre comes right to the edge of my dreams, no narrative, just presence, like a mother by her fevered child’s sickbed. I think, I will keep mornings free for the rest of my life so I can go back to bed and hope to meet him there. He will take my hand and lead me somewhere. He is on the edge of sleep, and all I have to do is go there to be with him. I will go back to sleep each morning and meet him in the dream-space, and then I will be able to carry on with my day.

Oh my darling where did you go?

The language of flowers is not a language I grew up knowing. I grew up in the city, Washington, DC, the child of transplanted New York Harlem apartment people who did not know how to grow things. There were crocuses in springtime that my mother planted along the walkway of our townhouse, and I remember my grandmother— born in Selma, Alabama, and reared in Birmingham, then Washington, DC—advocating that we plant hardy pachysandra, which her sister in Durham used as ground-cover.

As a little girl in Washington I liked to sit on the ground beneath the dogwood tree in our tiny front yard at 819 “C” Street Southeast and search for four-leaf clovers. Clover was all I knew of “flower;” that was the time I spent in “nature.” A family joke was, they say I bawled when first placed on grass to crawl. At my elementary school, honeysuckle vines and mulberry trees grew surrounding the parking lot; my best friend and I would gorge at recess in springtime and imagine ourselves foragers in the wilderness. Rain puddles seemed as significant as lakes or ponds. In our neighborhood in the Sixties when I was growing up, country people still lived on Capitol Hill. I’d see them in their front yards catching a breeze when our family would go for slow walks on weekend summer evenings. In their yards grew geraniums and others that I thought of as the province of black people, Negro flowers. Though as an adult I have rarely been without fresh-cut flowers in my home—even a fistful of dandelions in a water-glass—I did not begin to know flowers until I knew Ficre and we moved into our house.

Now, the first full spring after his death, the still lives he set in the garden emerge. A small composition rises in a corner by the driveway: a stalk of grape hyacinth, scientific name muscari, derived from “musk” referring to the intoxicating scent which Ficre knew was my favorite olfactory harbinger of spring. A rare, almost cocoa-colored tulip which I now learn was originally planted in the Arts and Crafts era to match those houses in the style of ours. A shiny, frilled, purple-black parrot tulip that feels as late Victorian as the time period of the house. The whole cluster forms a dark, strange, gorgeous little still life, as carefully made as Ficre’s paintings, with histories and etymologies and referents that continue to unfold.

With each community of flowers in the garden, a story: white and pink-streaked peonies, which always, always blossomed on my birthday, May 30, his birthday gift to me each year. There was never not a peony clipped and in a short drinking glass to greet me on my birthday morning, its head heavy with morning dew and often a small beetle. This spring I learn our peonies are double blooming, the rarest and most revered by gardeners. Ficre did not see them achieve this status but he was more patient than anyone I ever knew by far, and knew they would come up in the future. This year, the peonies are magenta and white, and they blow open as big as toddlers’ heads, and soon they are spent and rotten, their petals brown and withered in the ground. Over and done until next year.

I look along the corner of the house and see the purple and white climbing clematis—if stars could be violet these are violet stars—climbing across the side gate as they did up the fencing on Livingston Street. Once our friends Cindy and Dick came for dinner and Cindy walked through the garden and oohed and aahed at the clematis. How did he make it grow so abundantly? That was in the days when my sons called each other “Brother,” as their names, and Bob Marley’s gospel of diasporic love and righteousness played in their young ears each day.

And then, this morning, out the back: huge, ruffled, cream- and apricot-colored iris. I have never seen these before. I bring the boys to the window, one at a time. “Look,” I say, “Daddy is saying hello to us,” and he surely is. Through the stalks and the blooms come the touch of his hands on the bulbs. Hi, honey, I say, and I hear him say, Hi, sweetie, and the hurt is completely fresh, the missing, the where have you gone. I do not feel comforted. And I am still bewildered, from the archaic, “wilder”: to be lured into the woods, into some wildness of mind. Will I really never speak to him again?

I look again at the color of the iris. It appears in many of his abstract paintings. The New Haven Italian printers who manufactured a catalogue of reproductions of his book kept coming to the studio to make color corrections, because they said, “This color doesn’t exist.” It only existed in his paintings.

Ficre did not paint what he saw. He saw in his mind, and then he painted, and then he found the flowers that were what he painted. He painted what he wanted to continue to see. He painted how he wanted the world to look. He painted to fix something in place. And so I write to fix him in place, to pass time in his company, to make sure I remember, even though I know I will never forget. “This is a compound like the one I grew up in,” he said, when we first visited the house. He squatted in the yard like it was land to be farmed. Compound: where families were safe, even when they were unsafe. Where families were families.

Flowers live, they are perfect and they affect us; they are God’s glory, they make us know why we are alive and human, that we behold. They are beautiful, and then they die and rot and go back to the earth that gave birth to them. ❖

Excerpted from THE LIGHT OF THE WORLD by Elizabeth Alexander. Reprinted with permission from Grand Central Publishing, copyright © 2016 by Elizabeth Alexander. All rights reserved.

Previous

Previous