Stone walls do not a prison make.

Nor iron bars a cage

Minds innocent and quiet take

That for an hermitage.

Thus whispered Dorothy L. Sayers’ Lord Peter Wimsey to his beloved Harriet when she was wrongfully imprisoned. He was quoting a poem, written in 1642 by Richard Lovelace, who was himself imprisoned for his loyalist politics. This poem was written to his lover, Althea.

Ah, but some gardeners love their gardens as much or more than any human! For them—and indeed many less ardent gardeners—winter itself is a kind of imprisonment; stuck inside, no longer able to potter amongst our plants, stopping occasionally to admire a particular love, urging a little here, watering a little there…. Now all we can do is long to be outside again, while we thumb catalogs and wait for a spring that never seems to come. (Still, we are luckier than our ancestors, shivering in drafty, dark houses, crowded together, and sometimes short of food.)

In the past, the garden itself was often walled, both to keep the unwanted out and sometimes to keep women or children in. It was thus with that first garden, Eden. In Milton’s Paradise Lost, the garden was surrounded by a barrier, probably a high wall, which was standard in ancient Persian gar-dens and common for gardens of Milton’s time. Satan himself had to find a way into Eden, so before he took the form of a snake, he became a cormorant and flew in. There he wickedly perched on the Tree of Life, “devising death.”

When Adam and Eve were expelled from the garden, an angel with a flaming sword was recruited to guard the only entrance. A Medieval legend told that Adam did manage to creep back later to steal seeds from the Tree of Life (which grew into the tree that made Christ’s cross). Perhaps, as happens with neglected gardens, the wall fell into disrepair, and Adam found a hole in it.

The walled garden of Eden and the Old Testament garden of Solomon’s bride, who was herself described (in the Song of Songs) as a “garden enclosed”—these images were adopted by the Medieval church and represented by Mary, whose virtue was compared to a walled garden. A garden appears frequently in paintings of the Virgin. Sometimes in paintings of the Annunciation, Mary sits in a walled garden with a broken wall in the background, symbolizing how sin would have entered the world before her conception.

An actual small garden was often called a “paradise” garden, or hortus conclusus (“enclosed garden”). There, walls protected fruit and flowers from the wind and kept the fragrances of plants (thought important to healing) from dispersing. They also provided privacy. There was little privacy indoors. Even in castles, the servants habitually lived and slept in close proximity to their employers, and the rooms were large, drafty, and dark—for very little light penetrated the thick walls.

A giardino secreto (“secret garden”) was a small walled garden where lovers, legal or clandestine, could meet. In the Medieval Romance of the Rose, the “lover” finally penetrates into the garden, “a rosir charged full of rosis,” to reach his heart’s desire (the symbolism being somewhat obvious).

Walls were often thought necessary to keep intruders out. Crusaders returning from the Middle East brought back memories of beautiful enclosed gardens where women could relax and be protected. The wall around these little gardens was sometimes called a “chastity.”

Walls were also used to keep the women in. Both the Chinese and Japanese had separate private gardens for women, and the harem gardens of the Middle East were inviolate. Penalties for trespassing were very severe.

In China, the walls were often undulating and long, like a dragon’s back—for dragons were sacred and powerful creatures. In the Chinese Craft of Gardens (written in 1631 by Ji-Cheng), a surrounding boundary should have “a little gap left in it for the dogs to go out and greet visitors.” In Japan, garden walls were more often straight. Sometimes a Japanese contemplation garden was viewed from its boundaries rather than from within. A neutral area, called a nantei, separated the garden from its viewer and was a boundary which only the gardener was permitted to cross. There might also be a viewing platform from which to absorb the spirit of the garden without interfering with it.

Roman law decreed that garden boundaries should be marked, and these were often defined by statues of gods, mostly in the form of herms, which were plinths with a human head on a plain column. Such gods could apparently do without limbs, but did not lack genitals, which embellished the column halfway down. Terminus was the god of boundaries, and his name came to mean “a boundary.”

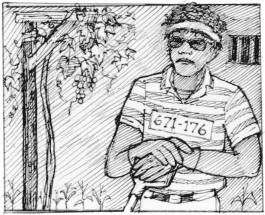

The real world has boundaries, and real prisons have walls—but some of these have had gardens, as well. [See “The Flower Man of Sing Sing,” in this issue. —Pat.] And some have been helped by being allowed to garden within the walls. Nelson Mandela kept a vegetable garden while imprisoned and even shared the produce with his guards. Many prisons these days have gardening programs, which can help those who garden enter another world, for a time at least.

In our prison of winter, we gardeners can’t work outside, though we are longing to do so. But it could be much worse—spring will surely come! Meanwhile we are free to dream and plan, thumb catalogs, see other gardens on TV, or even go to warmer climates and admire plants there.

For the walls of winter are made of time not stone—and will dissolve with the warmth of spring. ❖

Previous

Previous