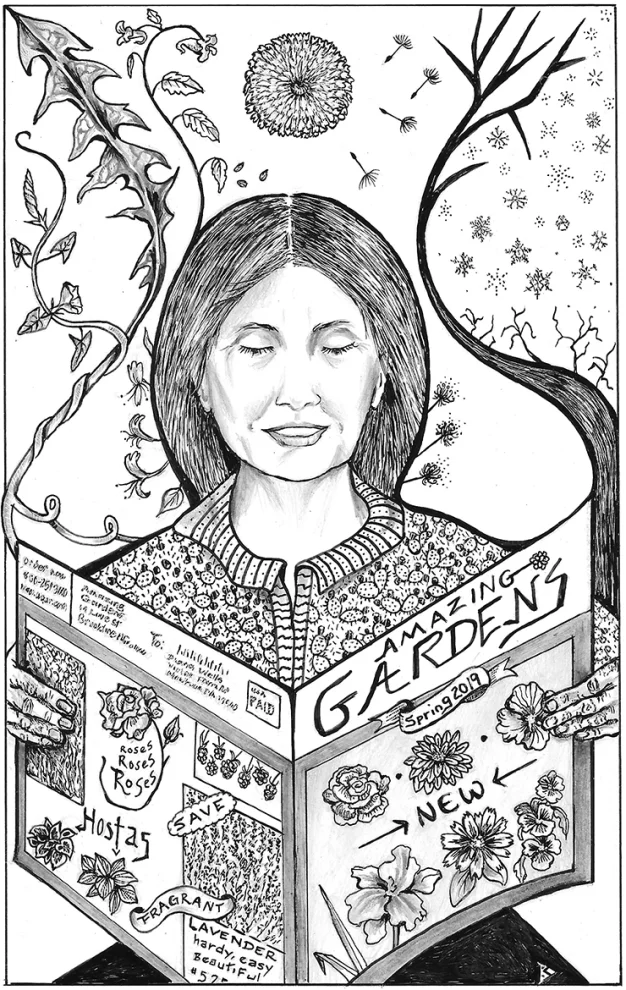

For me, one of the best things about Winter is that I don’t feel guilty about not weeding (as I do for most of the rest of the year). Instead, helped by catalogs, I can indulge in my dream garden for next year—a mental paradise similar to the one Adam and Eve enjoyed before they were turned out to deal with “tares and thistles.”

My garden looks pretty good now with all the weeds dead (I should say dormant). I remember the day last August when I finally went out to weed and, seeing a tick on one arm and mosquito on the other, decided it simply wasn’t worth it. I would henceforth think of my garden as “wild.” How much difference is there between a “natural” and “neglected” garden, anyway?

At the beginning of the 19th century, the romantic fashion for “picturesque” natural beauty was beginning to lose popularity. “Only by art in nature lost,” lamented William Wordsworth. Jane Austin, whose pithy comments on fashion can still make us smile, had Edward in Sense and Sensibility remark that “I do not like crooked, twisted, blasted trees…I am not fond of nettles, or thistles, or heath blossoms.” Soon neat, flowery gardens would be coming back, leading to the era of ”bedding out” (which I wrote about in the Summer Issue).

But, alas, the more artifice to a garden, the more weeds!

“Weeding! What it means to us all!” wrote Mrs. C. W. Earle in her 1897 book, Potpourri from a Surrey Garden. “The worry of seeing the weeds, the labour of taking them up, the way they flourish at busy times, and the danger that can come from zeal without knowledge.” (She went on to describe “an affectionate member of the family” weeding out “every annual that had been sown.”)

That’s one trouble with weeding—it requires knowledge and judgment, and a personal decision of what exactly a weed is. John Ruskin described a weed as a “vegetable that has an innate disposition to get into the wrong place.” Ralph Waldo Emerson said a weed is “a plant whose virtues have not yet been discovered.” Some weeds, like toadflax, dandelion, and bindweed, are (to my eyes) as lovely as any cultivated flower.

But beauty, as our mothers told us, is not virtue enough in itself. Weeds may be beautiful (or not), but they are always tough and pushy. Take bindweed, with its glorious pale pink and creamy trumpets. It is also called Devil’s guts. Why? Because it spreads rapidly and is almost impossible to eradicate. The roots can grow down to 18 feet, “deeper than one’s eventual grave,” as Vita Sackville-West wrote. And even if you could dig down there, you would not get rid of it. The tiniest fragment left will resprout into another vigorous plant.

Another weed that can’t be eliminated is goutweed, first brought to Britain by the Romans and then to America as an edible and healing plant (as its name suggests). Again, the smallest fragment left in the ground will make a new plant, which will eventually produce a host of delicate lacey flowers similar to Queen Anne’s lace. I pretend I planned that show when it appears! It may be edible, but I think it tastes horrible, though I may have to try it again if I get gout.

Weeds flourish where we garden, and the more we garden, the more they flourish. They have evolved to fill vacant spaces in even the poorest soil, and they are unbelievably creative travelers. An English Earl of Salisbury described counting 20 species of weed in the turn-ups of his trousers! Stowaways to America came in hay, in earth used for ballast, in every possible crevice and cranny. In 1638, John Josselyn, who called himself a “Colonial Traveler,” made a list of plants “as have sprung up since the English planted and kept Cattle in New England.” His list included dandelion, plantain, nettles, burdock, and fat hen. The last of these is good to eat and very nourishing, as are nettles in a delicious spring soup, and, of course, dandelions in salad. They probably were imported as pot plants.

Other “weeds” were brought in for their beauty, such as the Japanese honeysuckle—tenderly sent in 1863 (packed in a “Wardian” glass case) by Dr. George Hall from his Yokohama garden to become a pernicious (if fragrant) strangler of trees in much of eastern United States. In Australia, thousands of acres were overrun with prickly pear, brought in as a pretty houseplant. And some seemingly unlikely plants seriously threaten native species. Yes, you can have too many daffodils. In Bucks County, Pennsylvania where I live, a generous philanthropist donates millions of daffodils along our highways and parks. I wish he would plant our lovely native spring flowers, instead.

That’s not to say that all natives are desirable and good. How about poison ivy? Early settlers discovered it by bitter experience as it took horrible revenge on those who tangled with it—and I’m not one of those who claim immunity.

So, as I say, it’s nice and cold, and the weeds have “disappeared.” I know I’m only kidding myself and that, because I was lazy last Summer, bad things will happen next year. The jewelweed will have exploded its seeds far and wide. The goutweed will have crept even further. The bindweed will twist itself through my shrubs. There will be dandelions in the terrace and plantain in the vegetables. There will be poison ivy along the stream, and I will be feeling hot and guilty much of the time…

But it is Winter now. I can picture the soft green of the jewelweed after the browns of Winter. I can imagine the brilliant gold of dandelions on the bright Spring lawn. I can think of the tender translucent trumpets of bindweed winding through green branch-es. I can even recall the dazzling red leaves of Autumn poison ivy.

So, no, I probably won’t be a good weeder next year, either. But one season follows another. Whenever I feel guilty, I can always look forward to another “weedless” Winter! ❖

Previous

Previous