Here in central Indiana, most people herald Spring’s arrival when crocuses burst through the soil and buds start popping on the cherry trees. As a young girl, I learned that such signs could be premature. Cold snaps could cause early tulips to close their petals in tight protest. Many an Easter would find ladies attending church in flowered bonnets—and winter coats. For me, the most reliable sign that Spring had come to stay was the day I would arrive home from school to find my mother standing on the front porch, waiting for me to accompany her on our first mushroom hunt of the season.

“Hurry up,” she’d call. “Today promises to be good for us.”

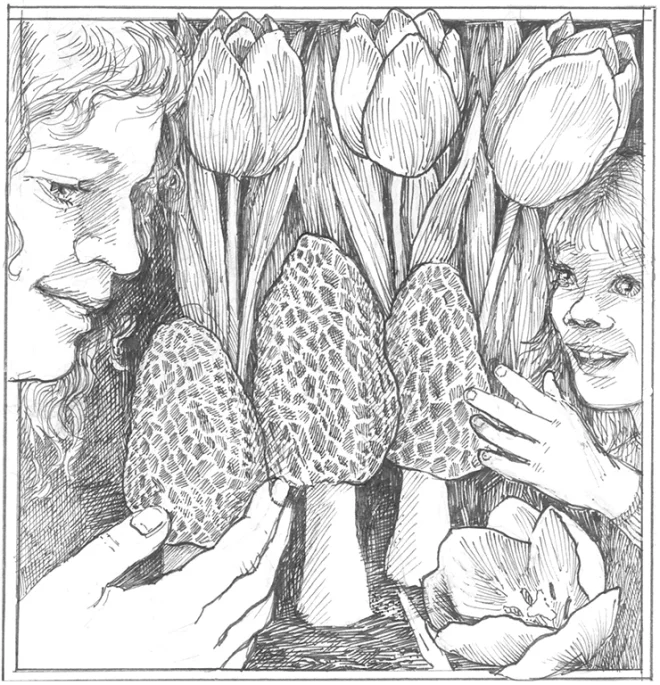

I would quickly change to my jeans, pull on my mud boots, and hurry out to the old Chevy, motor humming and mother at the wheel, ready to head to the woods. Finding elusive, mysterious woodland mushrooms was my mother’s favorite activity. We sought the yellow and gray cone-shaped morels, which resemble sponges perched atop ivory-white stems. Growing in wild, moist woodlands for only a short season each Spring, they are a prized delicacy.

Mushroom hunting is like treasure seeking: there are no guarantees. Mother had the reputation of being one of the best hunters in our town. Some people said she could smell them an acre away.

I did not share my mother’s enthusiasm. I would have much preferred playing with paper dolls at home or going roller-skating to tramping through muddy woods and slapping at mosquitoes.

Yet I was fascinated by the raw beauty and wonder of the woods. We would fan out in different directions on our quest, and I would soon be distracted by other discoveries: the bobwhite quail’s reassuring call of “All right, all, all right,” the rustle of leaves from a scurrying squirrel or the smell of fresh blossoms. My reverie would be broken by a shout: Mother had found her honey-combed prey. We would gather at the spot, hoping to find more spiked heads erupting from decaying leaves and brush.

Mushrooming required keen eyesight and great patience. Once I asked why we couldn’t just plant them in the garden and save ourselves a lot of trouble. Mother’s answer was that morel mushrooms were rare and so special that God, in His providence, chose to put them where he wanted.

Many times we would hunt until darkness crept upon us. If we found the places God had put them, we would leave the woods with our sacks filled with rewards. At home, we enjoyed the savory, nutty taste of the morels in soups and sandwiches or creamed on toast. Our favorite dish, though, was simply to dip them in beaten egg, roll them in cracker crumbs, and sauté them in butter. To me, eating the morels was the good part of mushrooming.

Mother, however, considered the whole process to be a joyful adventure. It brought delight to her each year. Mushroom hunting was her passion, and anticipating the season brought hope through many dismal winters. Then a Spring came when she could not go. Major surgery meant confinement at home with doctor’s orders of limited physical activity for the whole mush-room season. My brothers, sisters, and I undertook the hunt—at her urging—but we lacked the heart for it. Time after time, we returned home with little to show for our efforts.

Mother accepted her detention and spent her days reading or checking on her flower garden. One day as she poked among the tulips, she gasped, “Oh, come look!”

I hurried to see, fearful a garter snake had startled her.

“Look! Can you believe it?” she cried.

There amid the flowers was a golden morel on its ivory stem! “Here’s another one!”

Before long, we found a dozen mushrooms in the tulip bed. Mother was right. God sends the morels where He chooses. That year Mother couldn’t go to the mushrooms, so He sent them to her.

I still ponder the mystery of that wonderful Spring. That was the only time we ever found morels near our house in all the years we lived there, the one time Mother could not go to them in the woods. Those were special delivery mushrooms, sent by God at just the right time, to just the right place—to Mother. ❖

Previous

Previous