Read by Michael Flamel

This is a true story, though many facts have been exaggerated to protect the innocent. It’s also possible it happened so long ago that my memory might be playing tricks on me. My dad wanted us to grow up in the country, so he built a home in Bloomington, Minnesota, in 1948. Back then, our house stood all alone amidst the old farms and open fields where the Mall of America now sprawls. Developers hadn’t yet arrived to turn the fields into row after row of houses. Over time, Dad built homes for friends and relatives nearby, including my cousin Johnny Johnson’s family.

Johnny and I had plenty of adventures growing up. We cut asparagus in Spring near the future mall and worked Summer jobs on a vegetable farm by the Minnesota River. When the Corps of Engineers widened the river once too often, the farmer gave up and turned to managing one of the first McDonald’s in southern Minnesota.

One morning, before McDonald’s was boasting “OVER ONE MILLION SOLD,” Johnny was reading the fine print on his Wheaties box. It said, “If you are in any way disappointed with the performance of the product in this box, please write, and we will refund the price of the cereal.”

After breakfast, he scrawled a letter:

Dear Wheaties People,

This morning I poured my Wheaties in the bowl and waited for the performance, like the box said. I thought maybe they’d “snap, crackle, and pop” like that other cereal, or maybe dive in and out of the milk like dolphins. Since Bob Richards, the famous Olympic pole vaulter, was on the box, I even imagined a flake might use my spoon to vault back into the box. But by lunchtime, the cereal was too soggy to eat, and I hadn’t seen any performance. Please refund my money.

The Wheaties folks must have appreciated a good laugh, because a week later, Johnny received a letter with a check for two boxes of cereal. Feeling flush with cash, Johnny pooled his Wheaties windfall with his paper-route earnings and bought a packet of pumpkin seeds and a baby chick from Harris Feeds.

Johnny planted his pumpkins and named his chick Rupert. When he ran out of chicken feed, he fed Rupert Grape-Nuts. “Rupert can’t tell the difference,” Johnny said, but it seemed Rupert’s body could. Before long, Rupert was larger than any rooster, with a taste for Superman movies. After she outgrew the cardboard box in the basement, she was exiled to a relative’s farm for fear she might squabble with the neighbor’s oversized Labrador.

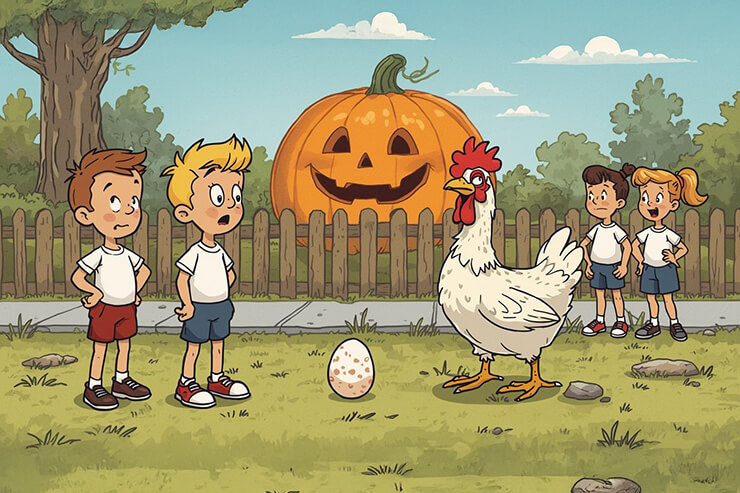

But Rupert wasn’t cut out for farm life. After picking a fight with a prize rooster and leading a chickens’ liberation movement, she was sent back home in time for Johnny’s pumpkins to ripen. One pumpkin vine had quietly crept into the yard next door, producing a gigantic pumpkin that rested squarely in Denny’s yard.

When Johnny and Rupert strolled over to collect their prize, Denny stopped them. “Hey, what do you think you’re doing with my pumpkin?” he shouted.

“Your pumpkin?” Johnny replied. “It’s mine. I planted it.”

“Yeah, but it’s in my yard. Finders, keepers!” Denny retorted.

“But if you follow the vine, you’ll see it starts in my garden,” Johnny argued.

Denny wouldn’t budge, and tensions flared as a crowd of kids gathered, anticipating a brawl. Rupert, ever the loyal bodyguard, puffed up her feathers, ready for action. But then Johnny spotted something on the ground—a fresh, warm egg, undoubtedly from Rupert herself.

“Hey, Denny,” Johnny called. “It’s Rupert’s first egg! Let’s go celebrate!”

The pumpkin dispute melted away, replaced by the promise of an egg feast. Neither boy knew much about the Armistice of 1918, but they somehow found peace in that moment. They scrambled to the kitchen to make something special with Rupert’s gift. Unfortunately, Johnny’s experience with eggs was limited to hard-boiled ones from the fridge, and Denny hadn’t seen much beyond what his mom prepared for breakfast.

Johnny let Denny crack Rupert’s egg. As the runny yolk spilled out, Denny exclaimed, “That’s funny. They’re usually hard and white when my mom makes them.”

“Yeah, same with my mom,” Johnny said. “Maybe we cracked it wrong. But we better eat it, or we’ll hurt Rupert’s feelings. She might never lay another one.”

With great effort, they downed the raw egg, grimacing at the taste. They then painted a face on the enormous pumpkin and placed it precisely on the line between their yards. After Halloween, they scooped out the seeds to plant more pumpkins next year and roasted the rest with their parents’ help. They even baked a pumpkin pie big enough to share with all the neighborhood kids. And when the party was over, Johnny taught Denny how to chop up the pumpkin shell for the compost pile, saying, “The earthworms will chew it up, in one end and out the other. That’ll make good dirt for next year’s pumpkins.” ❖

About the Author: Larry Johnson weeds the Old Gardening Party (the OGP) to keep the world safe for children, gardening, and storytelling. He has always had a garden, including one by the Gasthaus near the base where he served as an army medic in Germany. He and Tyler the Earthworm had a garden on the roof of Minneapolis Children’s Hospital where they started the first participatory pediatric TV channel for patients. Larry started school gardens and taught storytelling and video in the Minneapolis schools. He is author of SIXTY-ONE, and has helped Oscar Wilde’s “Selfish Giant” share his garden with the children in many places around the world.

Previous

Previous