One-third historical fiction, one-third romance, and two-thirds stories of women gardeners, The Last Garden in England is such a delightful read that the book truly adds up to more than a whole. Bestselling author Julia Kelly weaves stories of different women from a century ago to the present, the key connection being a gorgeous but forgotten garden designed by groundbreaking (fictional) garden designer, Venetia Smith. The author knows well both her gardening and how to write an enchant-ing, multi-layered romance.

This short excerpt portrays the day—April 25, 1907—that Venetia Smith discovers there can be more to life than nonstop work.

I have never understood “gardeners” who refuse to garden because it is unseemly for a lady to dirty her hands. Perhaps they don’t know the thrill of plunging a trowel into spring-softened soil to toss up the sweet, earthy scent of leaves and twigs and all manner of matter. By refusing to stain their aprons, they miss the sensation of damp, fresh dirt crumbling between their fingers or the satisfaction of knocking the dust off one’s clothes when retreating into the house for a well-earned cup of tea.

Then again, they also avoid the panic of being caught in a sudden, torrential rain with little cover.

Today I was alone in the poet’s garden, staking out the southern border with flags tied to sticks when the heavens opened. Almost immediately, the rain soaked through my shirt and plastered it to my back and chest. Then a crack of lightning pierced the sky and rattled my very teeth. I dropped everything to hike up my skirts and run for my cottage. I cut through the ramble, mud weighing down my hemline. A gust of wind tore my hat from my head before picking up my limp hair and thrusting it back in my face.

Around the corner of the cottage, I spotted a figure huddled under the little front porch.

“Mr. Goddard?” I asked, peering through the haze.

He looked at me from under his soaked hat, his grin sheepish. “Good day, Miss Smith. Lovely weather we’re having, isn’t it?”

“What are you doing here?” I asked.

He lifted a leather bag. “I come bearing gifts.” His smile fell.

“But you must come out of the rain.”

I took the cottage key out of my pocket and unlocked the door. “Given the circumstances, I think we would both do well to dry our boots,” I said over my shoulder.

Mr. Goddard hesitated, but when I began to ease off my boots, he gingerly put his leather bag down and did the same. As he finished, I went to the woodstove to coax the dying embers back to life. When I turned back, I saw that he’d lined his boots up perfectly with mine against the wall.

“I could make us tea while you change.”

I gave a start. “I do apologize. I’m forgetting my manners.” “I should apologize. I’ve barreled into your home without warning. Perhaps I should—”

“No. Please stay. And I will make the tea. This is my house, for a time, even if it sits on Mr. Melcourt’s grounds.” I moved for the door to the small kitchen.

He caught me gently by the elbow, bringing me to a pause in front of him. “Miss Smith, please, allow me. I can assure you, I’m not such a helpless bachelor.”

The warmth of his hand through the wet fabric sent a shiver up my arm.

In the privacy of my bedroom, I peeled off my wet things and hung them on the iron bed frame before dressing again. Everything felt deliciously dry and soft against my skin, from my chemise and stockings to my shirt and skirt. There was no saving my hair—not that it had been much to look at, jammed up under a hat for hours.

Instead, I dragged a comb through it and tied it back with a ribbon to keep it off my face. When I finished, I felt like a girl of eighteen again, fresh and hopeful.

The kettle was whistling in the kitchen when I returned. The fire was beginning to chase off the damp of the day, but rather than sit by it, I went to the large table in the center of the room. Across it lay plans, catalogs, and correspondence.

I put on my spectacles and flipped through the plans for the gardens until I reached the detail of the poet’s garden and began noting down an adjustment. A soft clearing of the throat brought me back. Mr. Goddard was standing in front of me, grasping a tea-laden tray with both hands.

“Where shall I put this?” he asked.

I quickly cleared a spot for him. Carefully, he set the tea tray down and drew up a chair.

Automatically, I began to set up cups and handle the strainer. “Do you take milk?”

“Yes, and a lump of sugar, even though Helen thinks it’s terribly childish of me,” he said.

I dropped the lump in for him and passed the cup over. “You should take your tea however you choose.”

“That advice doesn’t surprise me one bit coming from you.” “What do you mean?” I asked.

“You strike me as the sort of woman who does whatever she’s set her mind to without waiting for anyone else’s opinion.”

I flushed. “That’s not true. The very nature of my work means that I have to take a good number of people’s opinions into account.”

“You forget, Miss Smith, that I’ve watched you charm my sister and her husband.”

“I didn’t know that was possible,” I said before I could think to stop myself.

He only laughed. “You’ve seen Helen’s drawing room. Gilded and expensive. If she had her way, we’d be living with French knot gardens à la Louis XIV, with enormous Carrara marble fountains at the end of every sight line. And Arthur…I don’t know that Arthur has a creative bone in his body.”

“Despite his poetry?” I asked.

“You are too kind to his poetry,” he said. “Arthur’s garden would likely be a stretch of lawn with statuary and nothing else.”

“You forget that I’ve given them a sculpture garden.”

He studied me for a moment. “You have, and I suspect, much like the poet’s garden, you’ve done that because you know indulging their pretentions means that you’ve been able to create exactly what you want otherwise. Did they ask for an all-white garden?”

I smiled into my tea and said softly, “No.”

“Do you know, I’ve been wondering about why you’ve chosen the rooms that you did, and I think I’ve finally figured it out.”

“What is that?” I asked.

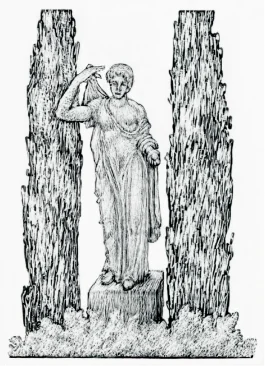

“Each room represents the life of a woman. The tea garden is where polite company comes to meet, all with the purpose of marrying a girl off. The lovers’ garden speaks for itself, I should think, and the bridal garden is her movement from girl to wife. The children’s garden comes next. I would guess that the lavender walk represents her femininity, and the poet’s garden stands for a different sort of romance than the lovers’ garden.” He sifted through the plans on the table and pulled free the detail of the statue garden. “Aphrodite, Athena, Hera. All of the pieces in the statue garden will be depictions of the female form. Am I right?”

I stared at him, my mouth slightly open. It was a little trick I used sometimes, weaving in a theme to the plantings. No one had ever noticed before, yet this man had seen right to the heart of it.

“The one thing I don’t understand is how the water and winter gardens fit,” he said.

“I’ve always found water to inspire contemplation and introspection. I meant it to represent a woman’s interior life.”

“And the winter garden?” he asked, leaning in.

“Her death, of course.”

He sat back in his chair, his cup nearly empty now. “I haven’t shown you what I brought you.”

He retrieved a bag stained dark brown with age and rain, pulled out a bundle of muslin, and unwrapped it in his lap. When he was done, I could see three plants with their root structures bundled up.

“You brought me hydrangeas,” I breathed.

“Hydrangea aspera Villosa. I overheard you mentioning that you enjoyed them when we visited Hidcote,” he said, handing me one of the plants and taking his seat. “Mr. Johnston was happy to oblige in exchange for the delivery of several ‘Shailer’s White Moss’ he is thinking of planting.”

“You brought me hydrangeas,” I repeated, touching one of the leaves. “Thank you.”

I looked up and found him staring at me with such tenderness, my breath hitched. I’d seen that expression before, between my parents in a quiet moment when they thought no one else was watching. Never before had I thought that anyone would look at me that way, and I knew that I couldn’t turn away from it without answering his unspoken question.

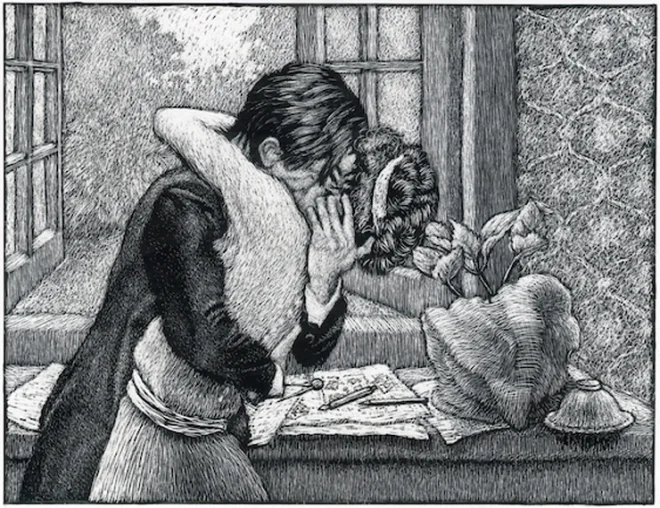

Deliberately, I set down the plant and rounded the table until I stood before him. His eyes never left mine as I reached for his hands. His thumb came to rest on the top of my hand, playing tiny circles over my skin. For a moment, we simply stayed like that and then, slowly, he pulled me down until the back of my thigh brushed the top of his.

“Miss Smith…Venetia…”

His right hand traced up my arm, to my waist. His other hand rose, and he let the pad of his thumb rest against my lower lip.

“I didn’t come here to…” he said, his voice a whisper. “That is…” I turned my lips into the palm of his hand to kiss his warm skin and whispered, “I know.”

He tilted my chin to kiss me in kind.

It had been years since I had been kissed. I could remember the thrill and fission of passion that accompanied one, but I’d forgotten the comfort. The feeling of someone else’s skin against mine. The surety of a pair of hands holding me in place.

We danced in silence, his hands spreading against my back as I twisted into him, my arms wrapped around his neck as he kissed me urgently enough to bow my back. When my fingers twined in the damp hair at the base of his neck, I thanked God for the rain.

A falling log crashed against the metal of the stove door, jolting us apart. We both laughed at our foolishness, but still the moment was broken. I slid out of his lap, immediately missing the warmth of him and his comforting scent of wet wool.

“Venetia,” he started after a moment.

I sighed. “I understand, Mr. Goddard. You are my employer’s brother, and—”

“I wish you would call me Matthew,” he interrupted. “I don’t want to go back to Mr. Goddard and Miss Smith.”

“But why?” I asked as he donned his still-wet coat and slung his bag over his shoulder.

“Because”—he smiled—“I’ve desperately wanted to kiss you since I set eyes on you.” ❖

From THE LAST GARDEN IN ENGLAND by Julia Kelly. Copyright © 2021 by Julia Kelly. Reprinted by permission of Gallery Books, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Previous

Previous