If you think Robin Hood wore green tights because of color preference or to make a Sherwood Forest fashion statement, think again. Robin wore green in homage to the Green Man.

And who, you may ask, is the Green Man? Well, first off, he’s old—very old. He existed long before the Christian era and has continued to pop up with regularity over the past 2,000 years. It’s only over the last hundred years or so that he has fallen into disuse, but even now, he still appears as a horticultural theme in various buildings and art objects.

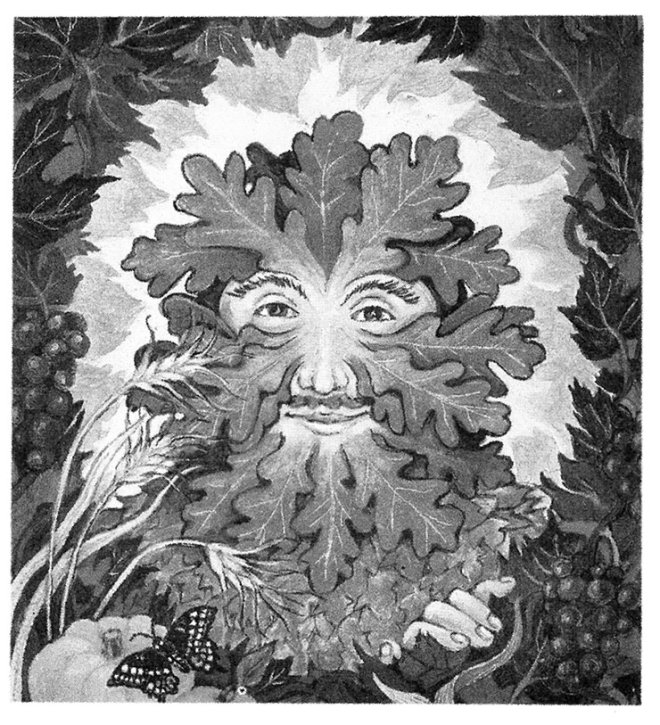

In form, the Green Man first appeared as a male head looking out of a mask of leaves (usually oak). In fact, his hair and most of his face—except for the eyes, the nose, and the mouth—were made of leaves. In France the Green Man is called la tête du feuilles (the head of leaves), or les feuilles (the leaves), or le feuillu (the leaf man), and he has two names in Germany: Der Grüner Mensch or Blattmaske (leaf mask).

There are also representations of the Green Man with vegetation shooting from his mouth—and often from his ears and eyes—so that he resembles a character from a lighthearted horror film. He even appears as a character made entirely of vegetables (as Arcimboldo painted him), with fern fronds as hair, cheeks of apples or peaches, and a beard of rutabaga roots.

One would have thought The Oxford English Dictionary to be font-deep in Green Men, but its comments are limited to descriptions of the Green Man as one dressed with greenery to represent a wild denizen of the woods, a character who took part in outdoor shows and masques and was sometimes called a Jack-in-the-green.

And what did the Church do with the Green Man? Apparently it wrote no encyclicals about banishment. Rather, the character was beloved and immediately adapted into the local architecture of a vast number of churches and cathedrals. There are hundreds, if not thousands, of Green Men throughout the religious buildings of England, France, and Germany.

While my wife, Jean, and I were visiting the Great Cathedral in Exeter, we saw him high on a column with grape vines galore instead of hair. On a vaulting boss at another end of that great edifice, he looks out from oak leaves in the cathedral nave. Again in a choir corbel, an angel plays a violin and supports the Coronation of the Virgin on her head, while her feet stand upon a Green Man who, instead of looking up, looks down on the worshipers assembled below. And on a single boss in the cathedral ambulatory, there is a Green Man sprouting artemesia leaves, still looking happy after almost 1,000 years.

In his book Green Man, The Archetype of our Oneness with the Earth (Harper Collins, 1990), William Anderson describes many of the Green Men in Europe. Just a few examples include the great cathedral at Chârtres, where dozens of them look out upon the world, including three perched high on the south transept portal, the one in the center with a leafy mask, and the two on the sides spouting leaves from their mouths. In Rheims, two Green Men look out from the inner facade, and in Auxerre, a Green Man with a mustache of leaves supports the rafters above his head. The strangest Green Man is the one from the Chapelle de Bauffremont with his expression of the-world-is-too-much-with-me ennui; the craftiest one peers cunningly through a mass of acanthus leaves in Bamberg.

Recently, while touring Ightham Mote in Kent, we visited the manor house (built in the mid-1300s) and asked our guide if there were any Green Men in the house.

“Well, goodness gracious,” she said, “nobody ever asks but, yes, there is a Green Man. Go into the great hall and high up in the vaulting you’ll see his face looking down. He was thought to be a part of the world spirit cultivated by the Druids.” We went and there he was, guarding the hearth with as much dignity as any churchly saint ever did.

While touring the gardens at Forde Abbey, I wandered into the house. There the rails and supports on the grand staircase were made of wooden panels, and dozens of painted Green Men looked out at the passersby from a tangled mass of dark brown and black tree branches painted in a tortuous design.

He’s on the main gates to Kew Gardens, designed in the mid-1840s. And recently he arrived in our home garden, where his leafy visage looks out from a Japanese-style garden gate to the flowers and vegetables we hope will benefit from his benign presence.

So who is the Green Man? In the end, he seems not to be a pagan god or even much of a mythological character; more a symbol, an expression of being at one with nature, at one with life, and at one with the earth. Indeed, the spirit of the Green Man is probably best represented by the lines from Andrew Marvell’s poem, “The Garden”:

No white nor red was ever seen

So amorous as this lovely green.

Meanwhile the mind, from pleasure

less,

Withdraws into its happiness;—

Annihilating all that’s made

To a green Thought in a green Shade—

It’s a spirit that gardeners, the Green Men and Women of today, can certainly appreciate. ❖

Previous

Previous