Read by Michael Flamel

Dad may have been a geologist at work, but the first spring in our new Baton Rouge yard, my brother Dave and I learned he was also a botanical magician. A magician who had one remarkable trick: getting us to work in the garden. His opening show, early one Saturday, featured one small azalea he wanted to add to the sparse but beautifully blooming azalea beds left by the previous owner. Dave and I winked at each other. This would be a quick job.

It wasn’t.

Over the following weeks, we became both stagehands and audience for a long-term extravaganza of garden sorcery, a spectacle we named “Disappearing Saturdays.”

No kid is alert early on Saturday mornings, so we were easy marks for Dad’s landscaping legerdemain. All we wanted to focus on was getting done and getting gone.

Trick Number One: Distraction. He started off each Saturday with his traditional care-and-cleaning lecture: “To prevent rust, always wash the dirt off your shovel when you’re done. Then dry it and apply a light coat of oil.”

See how he made us think we were almost done?

Trick Number Two: Misdirection. After all, how long would it take us to plant one small azalea?

“This new Daphne Salmon should go over there, replacing that formosa. Then we’ll see.”

Then we’ll see? I wondered. Too late, Dad’s magic was already at work. One single bush transformed into an entire Saturday of sweaty labor.

Four hours and three bags of peat moss later, we were still playing musical plants, replacing well-settled azaleas with others, newly uprooted. Each planting left us with a displaced bush larger than the last. Each time, Dave and I were prayerful: Let this shrubbery resettlement end. Let us be freed!

The more I thought about the work, the harder it became. Suddenly I recalled our English class reading of “The Chambered Nautilus.” What had been only a flowery, symbolic poem at school now spoke to me directly of release. I silently pruned and grafted Holmes’s poem until I had created my own cultivar:

Build thee more stately flowerbeds, oh my hoe,

As the brief weekends go.

Oh, to leave here fast!

Let each new shrubbery, nobler than the last,

Shut thee from playtime with a bush more vast,

Till thou at length art free,

Leaving thy well-oiled spade against the live oak tree.

I thought it was quite good and felt well on my way to being a successful poet. What did I know? I was only 16.

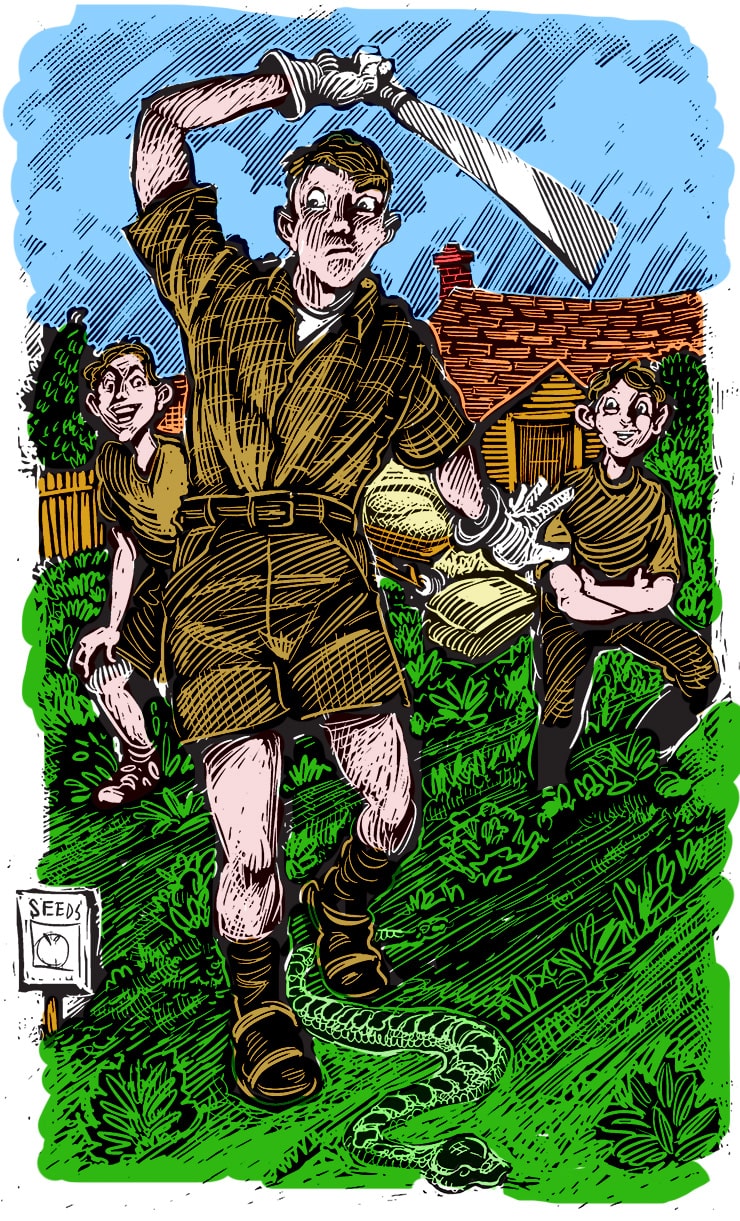

Such exploitative toil from teenage boys continued for several weeks. Indeed, Dad’s magic sessions showed no signs of ending, so one Saturday I suggested to my brother that we do some trickery of our own—with a rubber rattlesnake I had bought in a novelty shop in New Orleans. I distracted Dad with questions about the backyard, while Dave laid the snake near our work site. It did look real, like it was slithering in the leaf litter.

When Dad saw it, he cried out, “Snake! Snake! Stay back!” He hated snakes.

He rushed to his workshed for his Panamanian machete. Brandishing the three-foot blade, he advanced on the rubbery reptile. When Dad realized he had been tricked, he was not amused. We were dismissed (after we washed and oiled the tools, of course). He didn’t speak to us for several days.

I thought we had won.

When Dad returned from the nursery the following Saturday, he brought just one unfamiliar—and unsettlingly strange—bush he called a sweet olive.

“Just one bush this time?” I asked.

“Just one,” he said. Why did he look so smug?

Dad decided the sweet olive should be planted in the flower-bed just outside my room. A month later, a profusion of blossoms appeared. They gave off a heavy, cloying fragrance.

I had underestimated my father, a master of horticultural hocus-pocus.

Unlike affluent families, we had no air-conditioning. Instead, a central ceiling fan pulled air in the windows and blew it into the attic. The air flowing in my window passed through the flowers of the sweet olive, making my bedroom smell like the perfume counter at Maison Blanche.

I had only two choices: Gag or sweat. I chose to sweat and closed the window. It was the Tree of the Odor of Good and Evil, and I had smelled thereof. Henceforth I was to suffer in self-enclosed exile in the Louisiana heat. All because of that snake. Never mess with snakes.

Two days later, Dad came into my stuffy room. “No more snakes?”

“No more snakes,” I promised.

“Let’s move that sweet olive,” he said.

I jumped up and followed him. Twenty minutes later, the pungent bush was planted at the far end of the backyard.

After washing, drying, and oiling my shovel, I found a chameleon on the carport wall. I sat down to feed it some bugs—and looked out at the garden in our yard. You know what? I had to admit it was, indeed, beautiful.

Dad truly was a botanical magician. ❖

Previous

Previous