Six decades ago, as a preteen, I marveled at how a sunflower came to dominate my parents’ small garden. Then one decade ago, I had a flashback when my wife, Margaret, asked a simple gardening question. We had moved into an Alexandria, Virginia, townhouse with a parking side street, separated from the main street by a 10-foot-wide grassy median. A neighbor across the street had planted a few small flowers in the median in front of her house, and Margaret asked if we should plant some flowers, too.

“Have you ever grown a sunflower?” I asked her.

“No,” she replied. “Never.”

“Well, the sunflower is a gentlemanly plant,” I explained. “You should approach him with the sun at your back at happy hour, dressed in a French maid’s outfit. The sunflower will bow, and you should curtsy, then serve his cocktail. Manure tea, of course.”

Margaret played along but did insist, if she was to have a sunflower boyfriend, that he would have to have a dignified name to reflect such gentlemanly status.

“I’ll do more than that: your sunflower will have a plaque!”

I ordered the giant sunflower seed “SunZilla” from Renee’s Garden. A week later, the seeds arrived. Then, to ensure maximum growth, we dug a 2-foot-deep, 2-foot-wide hole and filled it with 60 lbs. of rich potting soil. We even added fertilizer “steroids” to promote tall growth. We planted three seeds and, following germination, retained the one with the most promising appearance.

But our sunflower needed its name. Being a chemist with an interest in history and having recently read a biography of Fritz Haber, I knew that it should be Fritz. Fritz Haber was a very dynamic and outgoing German chemist whose discoveries from the early 1900s are still the basis for fertilizer production (see the drawing of the plaque I made for him). During WWI, his affectionate wife (also a chemist) committed suicide in protest of his chemical warfare agent development. After the war, Haber tried to rebuild Germany, but his efforts were unacceptable to the Nazis, and he died in exile in Switzerland. Fritz would be our sunflower’s name!

Local school kids regularly walked by, observing the sunflower’s ever-increasing height. During May or June, when a sunflower might grow a foot a week, 3-foot-tall observers were amazed: “How it can grow so fast?” It is truly amazing when you realize that carbon dioxide from the air forms most of plant tissue via photosynthesis. Fritz eventually grew to about 12 feet and commanded a lot of attention.

The next year, Margaret was game for another sunflower boyfriend, but she insisted he have a new name. After some thoughts about sunflowers and chemistry, I thought of Herbert Dow. Dow started the predecessor of Dow Chemical Co. in the 1890s. He was also an ardent horticulturist whose legacy of the Dow Gardens consists of 110 acres of dazzling beauty in Midland, Michigan.

Herbert the sunflower provided an interesting lesson about the similarity between human and sunflower anatomies. When Herbert was only 10-weeks-old and 3-1/2 feet-tall, a powerful windstorm knocked him to the ground, bending and creasing his stem. But fractured sunflower stems, like human bones, can be aligned, immobilized with a splint, and will grow back together as strong, or even stronger, than before. Herbert’s sign post served as his splint, and he grew up just fine.

In 2013, the stage was set for a third sunflower boyfriend, George Washington Carver, by a road trip we made with a stop at Carver’s national monument and birthplace in southwestern Missouri. The historical displays were a delight to explore. The beautiful grounds were all very dog-friendly.

So was our George. When dog walkers were informed that canine “dietary contributions” were welcome, their visits became more regular. This eliminated the need for fertilizer and led to interesting conversations.

Peter, the fourth sunflower boyfriend, made his appearance in 2014. A Russian chemist from St. Petersburg visited and informed us that ever since Peter the Great brought sunflowers to Russia, they have been very popular there. What Russian science did to improve the sunflower was quite remarkable. Perhaps it inspired our Peter: he grew to 13 feet, our tallest sunflower ever.

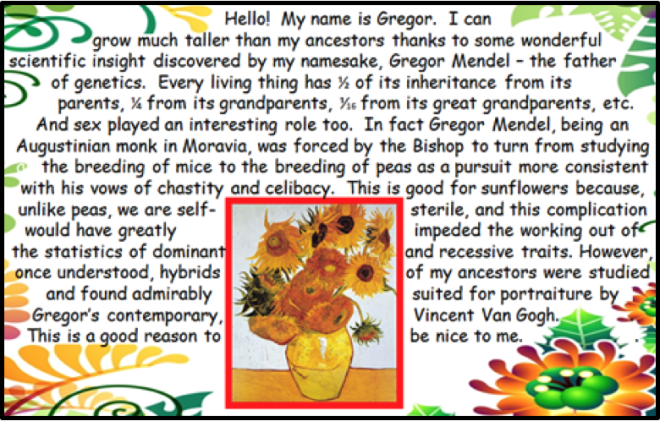

Peter led directly to Gregor, Margaret’s fifth sunflower boyfriend. Impressed by Peter’s height, we saved seeds from him to use in 2015. But none germinated. I cut some open, and I found them hollow. This mystery was solved when I read “The Making of the Red Sunflower” (Wilmatte Cockerell, July 1914, The Garden Magazine), in which Gregor Mendel’s genetic breeding discoveries were applied to sunflowers. It turns out that sunflowers are self-sterile. Without another one nearby, Peter could not produce viable seed—or Gregor.

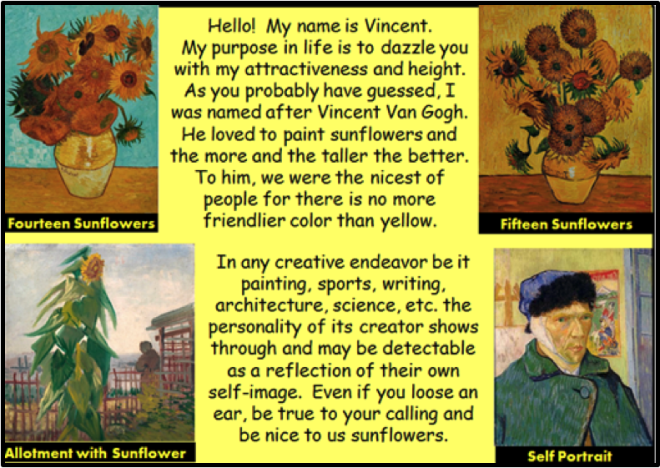

Gregor’s 2016 successor was Vincent. In the late 1880s, Vincent Van Gogh experimented with bold and dramatic colors along with a postimpressionism style. Sunflowers were a perfect subject matter, and Van Gogh made several striking paintings of them. A visitor to our Vincent said that he’d been photographing sunflowers for many years, but his pictures never captured their essence as well as a painting. Ah, sunflowers—lovely and elusive. Not the ideal boyfriend, Margaret (fortunately for me).

Returning to science, I named our 2017 sunflower Melvin. Nobel laureate Melvin Calvin used radioactive Carbon-14 in plants to study photosynthesis—in an attempt to reproduce it artificially! He never solved the problem, but Margaret solved hers: what to do with her boyfriend when it reached the end of the season. On October 31, she clad him in a ghost costume. Later that evening when Margaret made a midnight witch ride, instead of using a broomstick, she rode a sunflower stalk—off to her coven. Her next-day explanation of Melvin’s absence entertained many.

In 2018, we traveled in May and June to Alaska, all the way to the end of the Aleutian Islands chain. Having been born in Adak, Alaska, and leaving at the age of one, I have been plagued by two questions all my life: (1) “Are you an Eskimo?” (With a last name of Snow, it’s a great question!) and (2) “What is Alaska like?” (Now I could finally answer the second question as well as the first. But it came at a price: The sunflower did not get planted until the beginning of July. It was named Vitus (after Vitus Bering, who died exploring the Alaskan islands), but it reached only 3 feet when it bloomed. Lesson learned—plant the sunflower well before the middle of the growing season.

In 2019, Margaret wanted a sunflower boyfriend who could handle the heated political environment. Gunpowder Joe (Joseph Priestley) was a quirky scientist. When he identified the gas plants give off in sunlight, he called it “dephlogisticated air” instead of oxygen. He was also such a political radical that President John Adams had to give him a pardon to keep him from being deported!

The sign telling Gunpowder Joe’s story led to many friendly, humorous, and peaceful political discussions in the neighborhood.

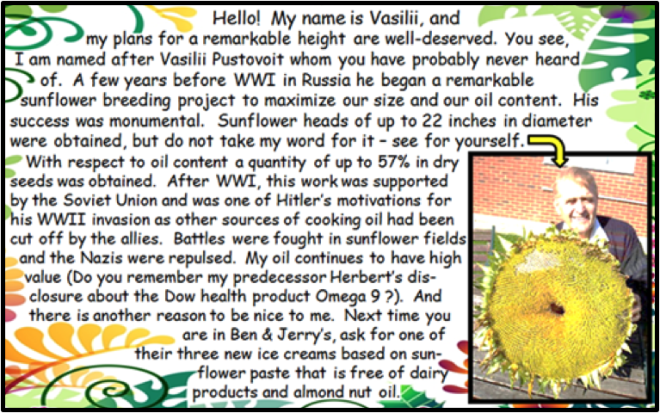

In 2020 (a year that brought big changes to normal living), Margaret asked how big a sunflower can get. The current best answer appears to have been provided by Russian scientist Vasilii Pustovoit. He produced sunflowers of exceptional size—22 inches across!—and seed oil content.

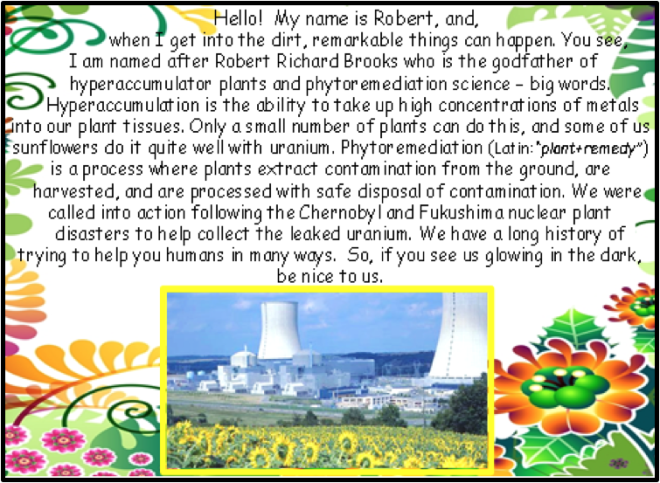

In 2021, the question came up: how deep can a sunflower’s roots penetrate? The surprising answer? Five feet, possibly more. And what sort of things do those roots collect? This was how Robert Brooks entered the realm of Margaret’s sunflower boyfriends. He discovered that sunflower roots help clean uranium from soil after nuclear accidents!

Our Robert faced a personal challenge. We had to replant him three times. The first three attempts, some unknown creature consumed the seedling two or three days after sprouting. I finally protected Robert #4 with a metal cage covered with an elongated plastic net. The time lost to false starts cost Robert two feet of height.

2022 brought the question, “Who was the first to take pen in hand and describe the sunflower in writing?” The answer is Thomas Harriot, for whom Margaret’s most recent boyfriend was named. He was a wonderful 16th-century scientist who learned and wrote much about the indigenous Americans. (Alas, he made the mistake of extolling the health benefits of smoking tobacco—only to die from cancer of the nose.)

Margaret’s Thomas had a catastrophe in July. After reaching a height of 10 feet with a top terminal bud just starting to expand, he was decapitated (we think by a demonic squirrel). It may have been a jinx to name this sunflower boyfriend after Thomas Harriot: his boss, Sir Walter Raleigh, was also decapitated—by King James I.

What a flower the sunflower is! Not only does it give us food, oil, beauty, and botanical boyfriends, it has a lot to teach us—and can be a lot of fun, too! ❖

Previous

Previous