Nobody in the county was better at coaxing food out of the ground than Daddy. He had the thumb, they said.

Daddy had a lot of sayings. The old ones, such as “If you chop your own firewood, you are warmed twice,” and “If at first you don’t succeed, get a bigger hammer.”

He had an old tiller, too, a Sears he bought used for $75. He had to spray starter fluid into the carburetor to get it to fire. It would sputter and pop, particularly close to the choke setting, and once it got going it would shake you to pieces. So another saying Daddy said was “Cutting ground with that tiller keeps you from having to pay to go to a gym.”

Then he used about a month’s worth of pay he got from the scrub machinist jobs he used to do and bought a new Troy-Bilt. The thing was dark red and shiny, and it started without him having to take the plug out to spray in starter fluid. Daddy said it was his set of golf clubs. While some men spent money on golf clubs or a boat, he spent it on that tiller.

Daddy read the 32-page manual that came with it and wrote the purchase date on the front in the thick half-print script that he’d practiced since he’d learned how to write in the sixth grade. They discovered late that he needed glasses, but he stuck with it until he’d almost aged out and graduated high school at 21.

The need to survive led him to work at any job that would have him, and eventually he wound up in the newspaper business. He started by throwing papers before dawn for pennies a throw. Then he got a job as a runner in the composing room, with its refrigerator-size Linotype machines that turned the creations of reporters, photographers, and editors into paper and ink. The newspaper company discovered he had a talent for fixing the machines that seemed to constantly break. So when an apprentice machinist job opened up, Daddy entered into his career.

The new tiller didn’t need much fixing. The Troy-Bilt’s tines churned behind the powerful five-horse engine rather than in the front like the Sears’, so all Daddy had to do was walk along and guide it. It even had a reverse gear, so when he came to the end of a row, he could back up a little, guide it around, and start on a new row, like mowing grass. No more shaking so much you wondered if your bones were going to stay together.

Daddy used a lot of Miracle-Gro. In fact, that was another of his sayings. Whenever my brother or I would outgrow our shoes or jeans, he’d say, “That boy’s been eating too much Miracle-Gro.” I knew he was making a little joke, but we ate so many vegetables from his garden that that was exactly what we were eating.

Daddy was not an educated man in the ways most people think of education. He said he’d have liked to have gone to college to study plants, like Luther Burbank, maybe even to learn how to grow new varieties. In-stead he watched shows like Jim Crockett’s Victory Garden on public TV and went to classes at the county extension agency. That’s how he met the extension service people. But they didn’t come out to his garden until the year of the giant sweet potatoes.

Daddy grew them pretty much like he always did. He’d start with the Troy-Bilt grinding up dirt powder-fine in two or three rows. It had a setting that got the rows into long high hills separated by troughs. Then he’d walk carefully along the troughs and put in the sweet potato sets. When they came up, he’d garden at ’em, hoe the weeds out, and use the Miracle-Gro.

He got a boom box radio from Radio Shack and started listening to classical music. He rigged up the boom box so he could record concerts from the public radio station. He had a shoebox filled with homemade cassette tapes with the names of the com-posers and conductors printed on the cassettes in his sixth-grade handwriting: Beethoven-Ormandy; Bach-Williams; Grieg-Karajan.

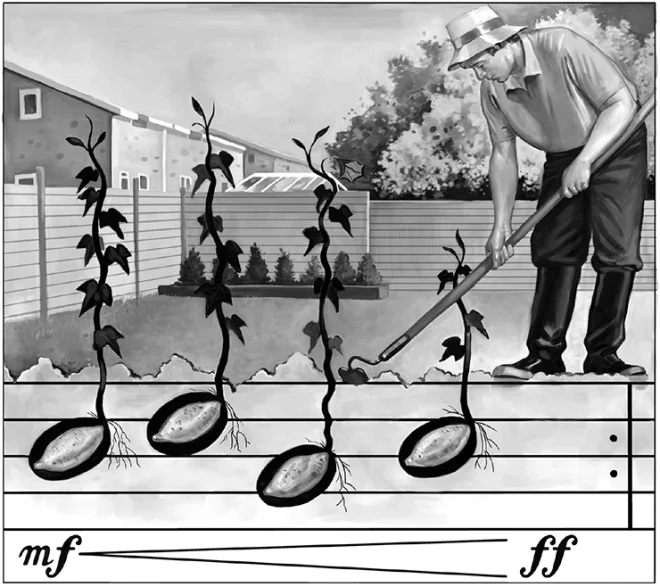

He got into the habit of playing the boom box while he gardened. He’d set it on an overturned plastic bucket at the edge of the garden while he hoed, smoothed the ground, and sifted the dirt, even finer for carrots and radishes that had to grow in dirt free of even the tiniest rocks to not come out all twisted and misshapen. It took a lot of time to get right, and while Daddy’s hands were busy with the dirt, his mind was conducting those orchestras.

The extension man came out to see the sweet potatoes after Daddy brought several into their office. They were whoppers—the extension man said he’d never seen ones that big. He said Daddy should think about entering them in the fair. He did. He got a blue ribbon and $12 that he didn’t bother to report on his taxes.

The next year Daddy took in some eggplants: big purple beauties that weighed three pounds apiece. The extension people made another trip to our house to look at Daddy’s garden. They said they couldn’t figure out what Daddy was doing that was any different from what a dozen other gardeners in the county were doing. So naturally Daddy put some in the fair—and won another blue ribbon and another $12. He also entered some more sweet potatoes. They were big, but not big enough. He didn’t get a ribbon in the sweet potato category that year.

Cucumbers were the next year’s super crop, and, like the two years before, Daddy made a trip to the extension office. The extension people were amazed: two-pounders that had to be cut into smaller pieces to fit into pickling jars. Out they came to see what Daddy was doing to get those huge cucumbers. And again they couldn’t figure out anything special. Daddy won a blue ribbon again for the cucumbers. He got $12 and a coupon for two boxes of canning lids. He tried sweet potatoes and eggplants and some other vegetables again, but only the cucumbers won a blue.

It went on like this year after year. Daddy would rake the fall leaves, cut them up into tiny pieces with the lawn mower, pile them up, hose them and turn them. Then in the spring he’d put the compost into the garden. He’d add lime each year to raise the pH and add a bag of 10-10-10 per section to finish off the nutrient levels, all the while listening to Shostakovich or Handel or Mendelssohn.

Each year he’d get into a different composer. From getting the dirt ready in early spring, through seeding and watching the sprigs poke through the tilled soil, through tying up tomatoes on wire cages, and finally harvesting the produce. Always, that boom box on a plastic bucket. Always, those homemade cassette tapes with whomever was the composer of the year. And always, that trip to the extension service to show off the vegetable of the year—and win that one blue ribbon from the fair.

Then one year Daddy backtracked. For some reason he took another liking to Beethoven. And that was the year the mystery started to unravel. Daddy’s boom box boomed out Beethoven all growing season long and the eggplants grew gigantic again.

The next year, he got onto another Stravinsky jag. The winner crop this time was those gigantic sweet potatoes. It was the same crop he’d won a blue ribbon with when he was on his first Stravinsky kick and played “Rite of Spring” over and over.

The extension people called the professors at the university. One of them made an appointment with Daddy and had a long discussion. They knew all the tricks about cutting up the leaves for compost and using Miracle-Gro and 10-10-10 and how babying the soil with a Troy-Bilt would increase yield and quality. But they’d never heard about Daddy’s secret ingredient.

They tried to duplicate Daddy’s results at the university, but gave up working on it after three seasons. They said they couldn’t prove it, but what Daddy said probably was the reason—eggplants love Beethoven, sweet potatoes thrive with steady expo-sure to Stravinsky, tomatoes groove on Grieg, and radishes and carrots for whatever reason are tickled into abundance by Shostakovich.

Daddy got old and quit gardening. He gave me the Troy-Bilt, and I started a patch. I also got Daddy’s boom box, because he’d begun conducting those orchestras from a recliner, listening to music on the big set. For two years I tried to garden like Daddy. But I was busy, so I skipped the classical music and the picking out tiny rocks and twigs parts. I got some pretty good sweet potatoes but never thought a minute about entering the fair. My carrots looked like number two pencils. No fair contenders, no blue ribbons, no $12.

Beethoven, Stravinsky, Grieg, Shostakovich, and Daddy—my apologies to you all. ❖

Previous

Previous