One morning last summer I was soundly schooled, by an elderly Chinese lady, on the proper way to harvest garlic. It was the best lesson I’d had in years.

It started the afternoon before while I was puttering in one of my back beds, when my neighbor Kaiyan came over. Kaiyan and I have become friends over our plants. My ability to speak Chinese is nonexistent; fortunately, her English is good and we are patient with each other. Kaiyan’s parents were on an extended visit from China. I grinned up at her in greeting, and she said to me, “My mother wants me to ask you why you are growing your garlic wrong.”

I was surprised. I’ve been growing about 300 head of garlic, successfully, for a number of years. “What does your mother think I am doing wrong?” I asked.

“Oh,” Kaiyan answered, “she says you should not be breaking off the long stalks.” Ah, now I understood. The sorts of garlic that grow best here in New England are hard-neck varieties. In June, hard-necks put up a long stalk, called a scape. When the scapes grow long enough that they curl into a loop, they must be removed. If you don’t break off the scapes, they will develop heads of bulbils and draw energy away from the bulbs growing underground. I told Kaiyan, without explaining, that I know from personal experience that the stalks need to be removed.

“Yes,” Kaiyan agreed, “my mother says it is good for the garlic to do that, but you shouldn’t break it off. You should pull it out of the plant.” I objected that the scape could not be pulled out, but Kaiyan insisted her mother said that was the way to do it.

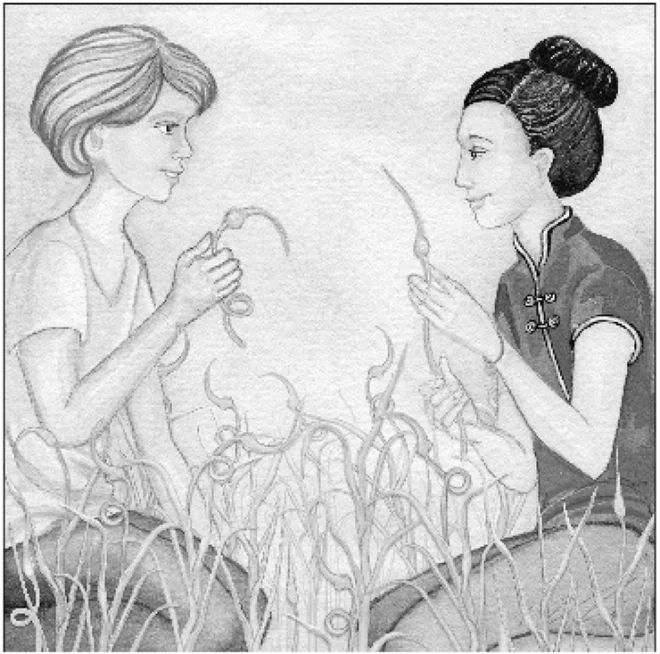

Kaiyan and I moved over to the garlic bed and began trying to pull out scapes. At first, I was quite anxious that I’d pull out the whole plant, but they are very firmly rooted and that didn’t happen. Most of the scapes pulled out an inch or so from the stalk, but then they broke off. Occasionally, one broke off inside the stalk, and pulled out cleanly. Kaiyan looked a little puzzled. “Perhaps,” I offered, “you grow a different sort of garlic in China than we do here.” This wasn’t such a far-fetched idea. The plant that I call a chive and the plant that Kaiyan calls a chive are entirely different. Maybe this is also the case with the garlic. I gave Kaiyan the scapes that we had pulled, and she headed home.

A little while later, she returned. “My mother says she will teach you how to do it the right way,” Kaiyan told me. “She says the best time is morning. She will meet you at seven o’clock tomorrow and show you what to do.” Now I was astonished. Kaiyan’s mother was going to show me how to harvest the right way? Garlic scapes? I should probably explain that I think garlic scapes are second only to kohlrabi in their vegetative pointlessness. (My opinion of kohlrabi? Don’t waste garden space on it. Just peel and eat your broccoli stalks instead.) Garlic scapes are huge, hot, and slightly lignified. They’re too tough to eat raw, and they take forever to cook. So I could not believe that anyone was making such a big deal about them. Nonetheless, I thanked Kaiyan and asked her to tell her mother that I would be excited to learn how she works with the plants.

The following morning I went out to the garlic bed at 7:00. As I knelt down to weed, I heard their door opening. I glanced over my shoulder and saw her mother trudging over.

Kaiyan’s mother does not speak English. She did not make eye contact with me, but came over to the side of the bed and began to work on the plants.

I crouched down to watch. Muttering softly in Chinese, she showed me that she had brought a large nail. She counted up four leaf junctures from the soil, then pierced the stalk with the nail. Then she grasped the scape where it emerged from the stalk and pulled, slowly and steadily, with both hands. There was a barely audible snap—and the scape slipped out of the stalk. She showed me again. This time I demonstrated that I understood to count up four leaf junctures, and she nodded her approval. I hustled to the garage, got my own nail, and began to try her method. I was definitely getting more of the scape than I did yesterday, but still about half the ones I tried were snapping off only a couple of inches down. Sometimes Kaiyan’s mother also failed and broke off one or two of the inner leaves along with the scape.

Then Kaiyan joined us. At last, we had a translator. “Does your mother know why this should be done in the morning?” I asked. She consulted her mother.

“The plants are cooler in the morning, and maybe they won’t break,” she said. “Also, the frost, no…” and here we worked together to help her find the right word, “…the dew maybe helps.” Then she added, “In China, it is very, very hot, so it is better to do this work early, before the sun is too high. These garlic stalks are very delicious; we use them in dumplings.”

Her mother said something again. Kaiyan translated, “My mother says you waited too long to do this. It is easier, and they are better, if you break off the stalk before it curls.” We found some garlic plants that were a little crowded and hadn’t grown quite as quickly. These scapes hadn’t begun to curl yet. I tried to pull one out. It slipped out easily, long and straight. That’s why I was having trouble before and why some had broken off inner leaves. We were trying to harvest the tougher, older scapes.

The part of the scape that had been pulled from inside the stalk was tender and white. Kaiyan broke off a piece and popped it into her mouth. Her mother also nipped off some of the blanched scape. She gestured that I should do the same.

I balked. With my sensitive Scandinavian palate, I do not eat raw garlic. I don’t eat any raw alliums. I couldn’t even eat cooked alliums until I reached adulthood, and they still bother my stomach. But both women were smiling at me expectantly, so I puckered up and took a bite.

It was sweet: tender, like the inner part of a grass stalk, and very, very sweet! Garlic scapes are a delicacy—I had just always harvested them wrong! It was easy to imagine tossing several cups of these into a large stir fry. No wonder the Chinese looked forward to harvesting them. They were amazing!

Imagine the courage that it took Kaiyan’s mother to be in a foreign land, where she does not speak the language, and step forward and teach a stranger. Imagine the love of the plants, the love of food, and the importance of preserving one’s culture that prompted her to show a stranger a new method.

I sent Kaiyan and her mother home with a large bag of scapes. That evening, Kaiyan’s son brought over a plate of dumplings that his grandmother had made. They were filled with stir-fried egg, spicy tofu, Chinese chives, and chopped garlic scapes.

They were delicious. I can hardly wait for my next gardening lesson. ❖

Previous

Previous