Read by Matilda Longbottom

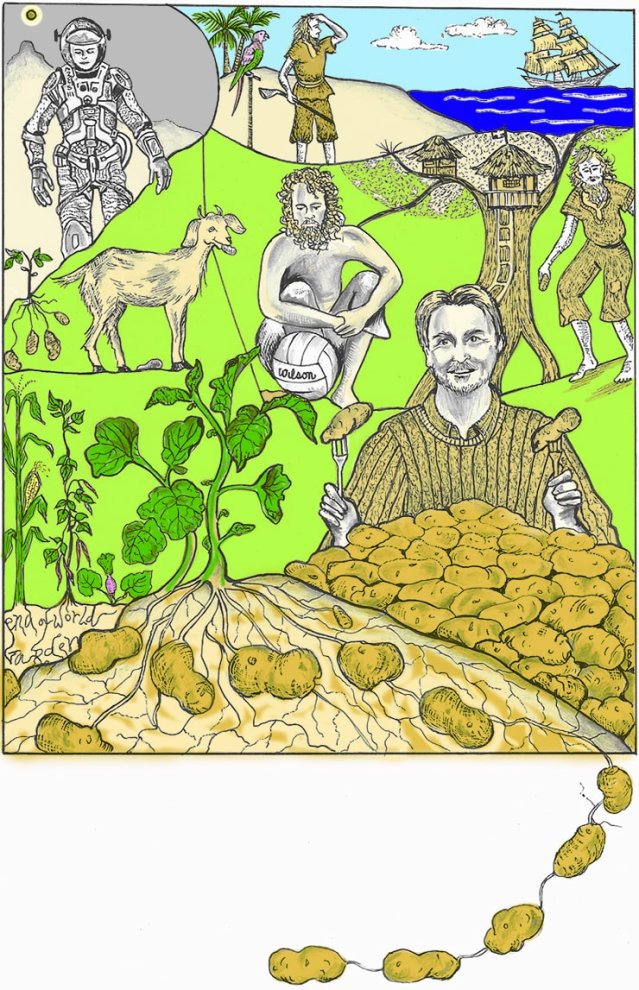

In Andy Weir’s The Martian, astronaut Mark Watney, victim of a freak accident, has been left for dead on Mars. Now 140 million miles from home, stranded and incommunicado, but very much alive, he has to figure out how to survive on his own for four years. Luckily Watney is a botanist, and his best bet, he decides, is potatoes.

It’s not a bad choice. Potatoes are prolific, filling, and packed with useful nutrients. One middling-sized spud contains 3 grams of protein, 2.7 grams of dietary fiber, 23 grams of carbohydrate—mostly in the form of starch—plus significant amounts of potassium and about half the adult Recommended Daily Allowance of vitamin C, almost as much as is found in an orange. In Richard Henry Dana’s best-selling memoir Two Years Before the Mast (1840), the crew, scurvy-ridden and on the brink of death, is saved in the nick of time by encountering a brig providentially provisioned with potatoes.

Watney’s Martian sojourn is the ultimate in Robinsonades—that is, a story with castaway and survival themes, named for Daniel Defoe’s famous 1719 book, The Life and Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe. Crusoe, the main character, was based on a real castaway, Scottish sailor Alexander Selkirk, who spent four years on a deserted archipelago off the coast of Chile, living on fish, crayfish, goat soup, and turnips. (He was finally rescued by a passing pirate.)

Almost all Robinsonades, inevitably, center around food. Cruose survives on goats and turtle eggs, and eventually manages to plant a garden, in which he raises barley, rice, and grapes. Ben Gunn, marooned in Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island, lives on goats, berries, and oysters. The Swiss Family Robinson, stars of the 1812 book of the same name, have the good luck to wash up on a lush, but biologically unlikely, island furnished with everything from coconuts, figs, and flamingos to sugarcane, sago, potatoes, buffalos, ostriches, honeybees, bears, elephants, and kangaroos. (And, yes, goats.) Tom Hanks, in the 2000 movie Cast Away, doesn’t do quite so well: He’s forced to eke out a living on coconuts and fish, with nothing for company but Wilson, a volleyball.

All these food troubles always make me nervous. Reading about them, I realize that I should can a lot more tomatoes. And maybe get some goats.

Not all survivors occupy distant desert islands or are stuck on uninhabited planets. Some—variously known as survivalists, preppers, or doomers—are right here, right now, preparing for the end of the world in the form of governmental collapse, global pandemic, nuclear or biological terrorist attack, environmental disaster, alien invasion, or asteroid strike.

Global meltdown hasn’t occurred yet, but there’s no denying that the possibility is there. (Think of the super-volcano under Yellowstone Park.) Threats of impending doom fuel survivalist movements, driving people to hunker down and prepare for the worst. Doomers stockpile weapons, water, iodine, bandages, blankets, batteries, gold, silver, and duct tape. And, of course, food.

A quick search online shows that food lists for would-be survivors are legion. Most emphasize shelf life (the longer, the better), nutritional content, and high calorie count. Common inclusions are canned salmon or tuna, dried beans, rice, beef jerky, pasta, peanut butter, and coffee. Salt, sugar, and alcohol—say a couple of cases of vodka—are often recommended. So are grains: buckwheat, dried corn, barley, oats, and quinoa. Those who can’t cook stash Ramen noodles and hard candy.

Food storage and preparation are keys to survival, but most of us don’t know as much as we think we do about either, according to Carol Deppe, author of The Resilient Gardener: Food Production and Self-Reliance in Uncertain Times. Thrown back on our own resources, we’ll have to turn to gardening—and survival gardening doesn’t mean the odd patio pot of mesclun and cherry tomatoes, but heavy-duty staple crops.

“Most gardeners know how to grow field corn,” says Deppe. “But most don’t have the knowledge to turn corn into gourmet-quality fast-cooking polenta or savory corn gravy or even corn bread—let alone fine-textured cakes.”

Well, in my case, too true.

Deppe’s recommendations for the end-of-the-world garden are corn, beans, squash, and potatoes. (Fifth and final survival food on her list is eggs. So you’ll also need to keep a flock of chickens.) Grains, beans, and (dried) squash are all nutritious, long-term keepers, Deppe points out, and potatoes not only yield more carbohydrate per square foot than any other temperate-zone crop but are dead easy to grow. Anyone with a shovel can plant potatoes, and potatoes, once planted, are cooperatively willing to grow on relatively lousy ground—such as,come the apocalypse, a hastily dug-up front lawn. They’re also simple to cook, provided you can build a fire (which brings up a whole different set of survival skills).

People, however, cannot live by potatoes alone. In order to promote the healthy potential of potatoes, Chris Voigt, executive director of the Washington State Potato Commission, once took a pledge to live on potatoes and nothing but potatoes—no butter, no sour cream, no cheese, no mushrooms and onions, no dollop of chili—for two months. At best, it sounds boring. At worst, it sounds dangerous. Medical doctors and nutritionists declared the plan nuts.

No single vegetable, no matter how pudgy and scrumptious, experts agree, can provide all the nutrients human beings require. With a diet of nothing but potatoes, we’d end up deficient in calcium, selenium, vitamins B12 and E, and vitamin A, which is essential for eyesight. Better to pair your potatoes with a garden’s-worth of beans, Brussels sprouts, broccoli, kale, and carrots.

Despite warnings, Chris Voigt survived his two months on potatoes with no particularly evil effects. (His blood sugar level was somewhat high—potatoes have a high glycemic index, which means that potato carbohydrates are rapidly absorbed into the bloodstream—but Voigt pointed out that his post-potato blood sugar readings were better than those before he adopted the potato diet.) Still, two months on nothing but potatoes is probably more than enough.

Luckily, astronaut Mark Watney, along with his potatoes, had vitamin pills. ❖

A Taste of The Martian

I couldn’t resist sharing a short excerpt from Andy Weir’s bestselling—and absolutely superb—novel (and now movie). Besides, what other garden magazine will tell you how to garden on Mars?!

At this point, the protagonist, Mark Watney, has been accidentally abandoned on the red planet and has to figure out how to survive until a rescue ship can come for him—in four years!

I need to create calories. And I need enough to last the 1387 sols until Ares 4 arrives. If I don’t get rescued by Ares 4, I’m dead anyway. A sol is 39 minutes longer than a day, so it works out to be 1425 days. That’s my target: 1425 days of food.

I need 1500 calories every day. I have 400 days of food to start off with. So how many calories do I need to generate per day along the entire time period to stay alive for around 1425 days?

I’ll spare you the math. The answer is about 1100. I need to create 1100 calories per day with my farming efforts to survive until Ares 4 gets here. Actually, a little more than that, because it’s Sol 25 right now and I haven’t actually planted anything yet.

With my 62 square meters of farmland, I’ll be able to create about 288 calories per day. So I need almost four times my current plan’s production to survive.

That means I need more surface area for farming, and more water to hydrate the soil. So let’s take the problems one at a time.

How much farmland can I really make?

There are 92 square meters in the Hab. Let’s say I could make use of all of it.

Also, there are five unused bunks. Let’s say I put soil in on them, too. They’re 2 square meters each, giving me 10 more square meters. So we’re up to 102.

The Hab has three lab tables, each about 2 square meters. I want to keep one for my own use, leaving two for the cause. That’s another 4 square meters, bringing the total to 106.

I have two Martian rovers. They have pressure seals, allowing the occupants to drive without space suits during long periods traversing the surface. They’re too cramped to plant crops in, and I want to be able to drive them around anyway. But both rovers have an emergency pop-tent.

There are a lot of problems with using pop-tents as farmland, but they have 10 square meters of floor space each. Presuming I can over-come the problems, they net me another 20 square meters, bringing my farmland up to 126.

One hundred and twenty-six square meters of farmable land. That’s real progress. I’d still be in danger of starvation, but it gets me in the range of survival. I might be able to make it by nearly starving but not quite dying. I could reduce my caloric use by minimizing manual labor. I could set the temperature of the Hab higher than normal, meaning my body would expend less energy keeping its temperature. I could cut off an arm and eat it, gaining me valuable calories and reducing my overall caloric need.

No, not really.

So let’s say I could clear up that much farmland. Seems reasonable. Where do I get the water? To go from 62 to 126 square meters of farmland at 10 centimeters deep, I’ll need 6.4 more cubic meters of soil (more shoveling, whee!) and that’ll need over 250 liters of water.

The 50 liters I have is for me to drink if the water reclaimer breaks. So I’m 250 liters short of my 250-liter goal.

Bleh. I’m going to bed.

Reprinted with permission from The Martian. Copyright © 2014 by Andy Weir. Published by Broadway Books, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

Previous

Previous