At my community garden in the Bronx, we grew many things. Sunflowers bobbed at the fence line, overlooking the cracked sidewalk and the rundown bus stop. Spindly peach trees offered up small, fuzzy fruits, many of which were stolen before they were ripe. Eggplant and tomatoes bravely forced their way through the crumbling soil.

This small urban plot, squeezed in between the highway and the Bronx River, was not the type of garden I was used to. So I didn’t realize how deep roots could go here—not until we grew peanuts from Cameroon.

The peanuts came with the refugees. One early spring day they arrived, a dozen uncertain faces: some old, some young, some in between. Many of them had fled political turmoil in West Africa or Southeast Asia, and had lived in the United States only a few weeks. Their guide from the international rescue organization led them in, speaking in brief syllables as she gestured to a daffodil and a pair of ducks on the river. The refugees seemed even more uncomfortable in an urban setting than I was. They didn’t know English, and they didn’t know the city, but when I opened the garden shed and began to take out our garden tools—hoes, spades, wheelbarrows—they smiled. This they knew.

Every week the refugees returned, eager for the familiar scent of soil, this reminder of their old lives on the land. An old man from Tibet calmly watered the beds, waving the hose slowly back and forth while nodding and smiling to himself. One of the rescue workers told us he had been a professor in his home country and was the author of several books. Two long-legged teenagers from Sierra Leone raced their wheelbarrows of mulch down the garden path. They were in school now but had been placed with much younger students in order to catch up on the language. A mother and daughter from Myanmar knelt side by side pulling weeds, speaking softly in Burmese. Their husbands had not yet been permitted to leave the country.

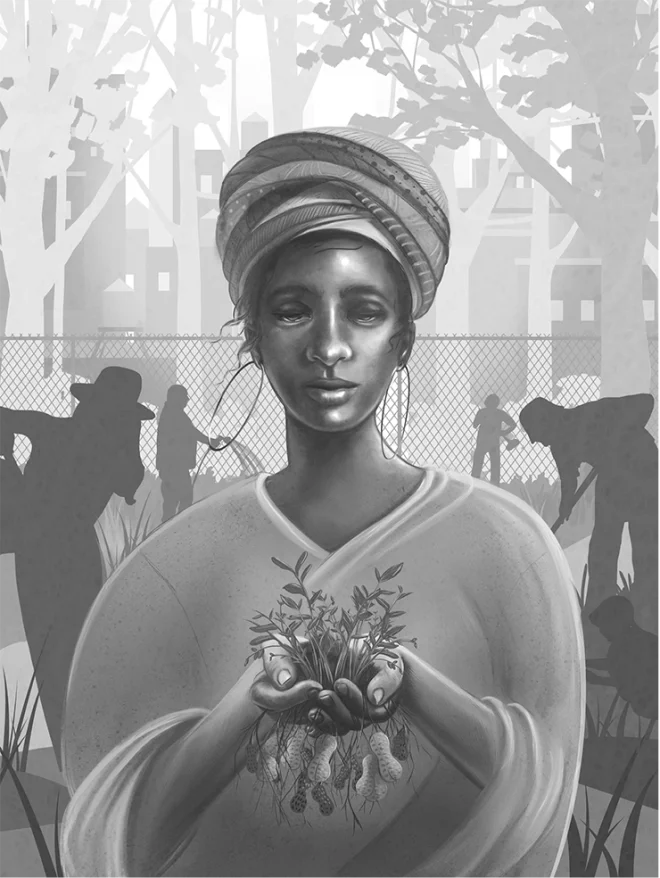

One woman, Angel, spoke better English than the rest. She wore flowing yellow blouses, hoop earrings, and a headwrap bright with floral designs. “In my country,” she told us, “in Cameroon, we grew corn, cassava, peanuts. We grew tous les choses. There was no one, personne, who did not farm.”

One day, Angel arrived at the garden with a small bundle clutched to her chest. “Come,” she said. When all of us had gathered round, Angel carefully opened a paper bag, crumpled and soft around the edges. It contained a few handfuls of tiny peanuts. “My sister has sent these, from our country,” Angel told us, “and I want to share them with you. We will plant them here.”

As we knelt together around a raised bed, recently cleared up of bindweed, no one thought to question whether peanuts could grow in the Bronx. No one remembered that it was almost summer, late for planting. No one worried whether the soil could offer all the nutrients peanuts need. We all stood in Angel’s spell, watching carefully as she showed us how to plant the peanuts a hand’s width apart, placing three or four seeds together in each small mound. Each of us planted a peanut in the ground—those of us who had planted peanuts many times before and those of us who had not imagined that we ever would. Then we waited.

After that, each week when the refugees arrived, they gathered at the peanut bed. The boys ran ahead to get there first. The older members of the group followed behind, craning their necks for a glimpse. On days when the group didn’t visit, I snuck over to check on the peanuts myself. Would rats or squirrels dig them up? Would the packed soil prove too hard for them to grow? Would summer rains wash them into the Bronx River?

But the peanuts grew, and so did our group. The refugees began to come twice a week, then three times. Some of them brought new friends along. The peanut plants grew runners. They flowered. They put out more runners. They spread.

Other community gardeners visited the bed to examine this curious crop. The peanuts looked healthy, but what was happening beneath the ground?

Autumn came. Pieces of litter blew against the garden fence. Pumpkins and zucchini ripened. Yellow gingko leaves, twirling down from the street trees, came to rest in our vegetable beds.

At last it was time to harvest. We planned a celebration in the garden: Each family brought a dish from their own country, and we strung up ribbons and balloons. The children played tag around the little peach trees, while the grown-ups laughed and spoke to one another in many languages. New visitors stepped tentatively into the garden, lured away from the bus stop by the sound of music and voices. We picked—squash, kale, cauliflower, the last of the tomatoes—and divided the bounty among all the guests.

Then all of us, 40 or 50 people, gathered at the peanut bed.

As we watched, Angel bent down, her enormous hoop earrings swinging in her ears. She gave the first plant a solid tug, bringing it up all at once in a bundle of leaves and runners and roots and soil. She shook it to clear off the soil clumps, and we all leaned closer. There they were: tiny pale peanuts clinging to the end of each runner.

The guide from the rescue group plucked a tiny peanut and put it tentatively in her mouth. Suddenly her face curdled, and she spit the nut back out. No one spoke. I stared at the plant in dismay. Had the peanuts rotted in the rains? Had mold set in?

Angel laughed, a deep hearty laugh low in her throat. “We have to dry them first,” she said, her voice flowing richly over the group. “After two, three weeks, then—then comes the eating!”

We all surged forward then, grinning foolishly, to pull up our own plants and get a look at the peanuts. I rolled one between my fingertips. They were soft, with hardly any definition between the nuts and the surrounding shell. They would not be like peanuts from the grocery store, even when they were dried. Not like what I was used to. But I didn’t mind.

We carried the peanut plants in a parade through the garden. A plant would be carried back to each household, where it would be hung to dry before the peanuts were roasted and salted for eating. The garden would close for the winter and lie dormant in the cold and ice. But in the spring we would all be back. We all knew the truth now: Roots could be put down, even in hard-packed city soil. If peanuts brought all the way across the sea from Cameroon could grow in the Bronx, then anything—and any of us—could grow here, too. ❖

Previous

Previous