You have Parkinson’s.”

Hearing those three words almost a decade ago shocked and scared me. Most of all, it made me mad. I pictured the few people I ever knew with PD: shuffling, stooped over, shaky, and downright slow. Although I was 64, I was anything but.

A second opinion confirmed the diagnosis, and after several months in denial, a near-fatal accident and two months in bed forced me to face facts: it was time to slow down.

I was about to retire anyway from a teaching career and was looking forward to putting some serious miles on my motorcycle. The diagnosis killed that idea. Of my remaining interests, gardening was number one.

I earned my gardening stripes in my early twenties, working for a master landscaper who specialized in Japanese gardens. Ever since, I’ve looked for opportunities to work with rocks, shrubs, flowers, and trees. Even so, gardening didn’t become a priority, let alone a passion, until Parkinson’s reorganized my life.

I know that PD by itself isn’t going to kill me, but it is progressive, degenerative and, as yet, incurable. Parkinson’s has many different faces, the most challenging of which are tremors or shakes, wild fl ailing (called dyskinesia), slow movement (bradykinesia), and akinesia—the inability to move at all. The accompanying symptoms, everything from constipation to hallucinations, just add to the fun.

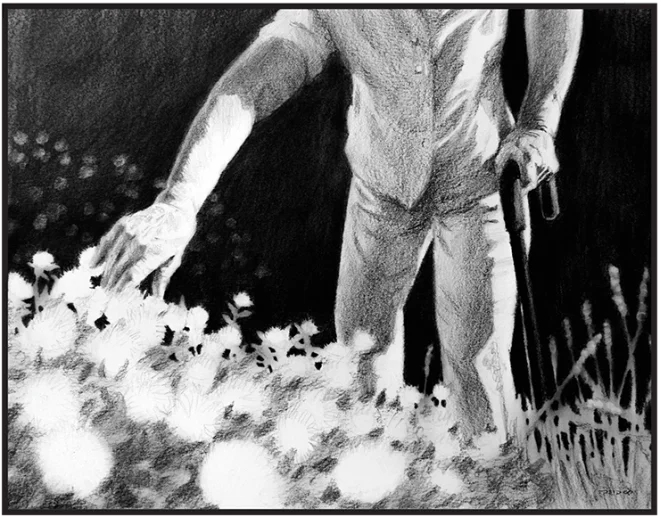

But there are ways to fight back. The most effective is exercise, something that’s been proven to slow the progression of the disease. In my experience, the best form of exercise is gardening. The constant bending, twisting, turning, reaching, lifting, and carrying works virtually every muscle while energizing the body and calming the mind. Best of all, you can do it outdoors in the sunshine and fresh air.

Gardening with PD can be frustrating. It can also be funny.

Case in point: A few years ago, I offered to help a friend with her garden. It hadn’t been tilled in years, so I rented a rototiller, the biggest they had. I started it up, released the clutch, and took off. The thing had front-mounted tines and just skipped across the surface in a kind of canter, going round and round as I tried to rein it in. I pulled the handles with all my might, but I couldn’t control it. In desperation, I dug my heels into the ground until we slowed down enough for me to take it out of gear and catch my breath. I put it back in gear, but this time when it tried to leap forward, I was ready and held it back. Now, though, it started digging straight down. The more I held it back, the deeper it dug. In the end I won, only because I was more stubborn than the tiller. None of this would have happened back when my muscles worked like they used to.

For the past four years, I’ve been busy gardening in my own yard in a small village in upstate New York. Our house is oddly situated, with the front entrance six feet lower than the road—the perfect place for a rock garden. There had been concrete steps lead-ing from the road to our front porch, but they were no longer safe due to the ravaging effects of the salt thrown down by the village snow crews over the years.

New steps had been built in front of the house when we moved in, and by the following June I was ready to incorporate the old steps into the rock garden of my dreams. Everything seemed perfect. I had already collected a number of interesting stones from a nearby streambed and piled them around the site. I was carrying a pail of topsoil, trying to balance it with my hands, and suddenly found myself doing the “Parkinson’s Shuffle” on the loose stones—and flying through the air. I landed hard on my knee on a thick slab of bluestone. There was a loud “pop,” and I knew in an instant that my rock garden would remain a dream for another season.

The “Parkinson’s Shuffle,” by the way, is very real. People with Parkinson’s develop an instinctive fear of falling and tend to walk hunched over, taking baby steps, barely lifting their feet. Unfortunately, the shuffling makes falling all the more likely.

I was right about the garden season being over for me. But it wasn’t over for my garden. I have the best partner in the world, but she doesn’t garden. Luckily, I have many good friends who do, and they dug in to help while I sat in a wheelchair, my kneecap immobilized, kibitzing. One friend spent two days expanding our small stone patio. Another divided his irises, lilies, and asters for me, brought them over, and put them in the ground. Another pitched in with the weeding, and yet another shared advice and eventually her harvest.

My forced inactivity gave me time to think about the many plants I’d like to see in and by my rock garden. I visualized pockets of dianthus, lobelia, pansies, and sedum; beds of alyssum, impatiens, nasturtiums, and phlox; borders of azaleas and columbine, a trellis of morning glories, and patches of moss and ferns.

I spent that Fall and Winter putting together a seed-germinating operation in our utility room. My long confinement had made me overly eager to get my flowers going and I jumped the gun. I ended up with the leggiest hollyhocks and marigolds my friends and I had ever seen.

On the first nice day in March, I went out and reassembled a 12’ x 3’ planting box I had built some years before for carrots, on-ions, beets, and deeper-rooted vegetables. I had designed the box with screws, which seemed ingenious at the time, never imagining how hard it would be to operate an electric screwdriver with Parkinson’s. What should have taken half an hour took half a day. Worse, I positioned the box so close to the back fence I couldn’t get around it. I’d have to lean all the way across to get anything in or out of the ground. This is virtually impossible with Parkinson’s. I could no longer reach across anything or tilt to one side or the other without risk of tumbling into my work space.

I call this the Third Hand Crisis. I use one hand to hold the plant straight and at the right height while I back-fill with the other hand. The problem is, I need a third hand to keep me from tipping over. Without one, I have no choice but to lean on my forearm until the plant is in the ground, a decidedly uncomfortable position.

Uncomfortable positions are quite common with PD. I was help-ing a friend recently with some weeding when she had to leave to run an errand. As she drove away, I waved, lost my balance, and promptly tipped over and rolled into her onions. I lay there like an overturned turtle, staring at the clear blue sky. I had no idea how I was going to get up and back on the garden kneeler without crushing any more of her crop, but all I could do was laugh. It was a classic bradykinesia situation. I was stuck, not unhappily, but stuck nonetheless.

The fact is, I can get stuck anywhere—getting in and out of bed, sitting at the table, or just standing by the door, especially if I have to turn around. My tomato, pepper, and pea patch backs up against the house and is trellised on two sides. I can walk in easily enough, but have spent many an hour trying to turn around and walk out.

My legs can freeze up at any moment. It can happen while I’m standing with a pick or shovel. It can happen when I’m stoop-ing over to pull a few weeds, or when I’m just staring off into the distance. We live up the road from a busy country store, and many times I’ve watched cars go by and return 10 or 15 minutes later with me, like a statue, in exactly the same position. I’m considering hiring myself out as a gnome for local garden parties.

Lately a new Parkinson’s symptom has accompanied me to the garden: double vision. I discovered it when I was out pruning and cut my finger instead of the stem I was looking at, which was actually a foot away.

So why, with so many literal stumbling blocks, do I persist in gardening?

First, because gardening is one of the few things Parkinson’s hasn’t taken from me. When I’m outdoors working with the plants and rocks, weeding, or tending to the compost, I can feel my muscles at work again. My balance improves, my stress level drops, and I’m at peace with my lot, something I never could have imagined ten years ago.

And second, because I love it. Who can regret time spent mull-ing over catalogs, or gathering stones from a creek bed, all washed and unique? And who really minds a bit of weeding, especially if you wait until the ground is softened by a night’s rain? Then, with patience, you can get the root of the thing to come too, and know you won’t have to struggle with that particular character again. Ah, there’s a satisfying moment.

And precious. ❖

Previous

Previous