Read by Matilda Longbottom

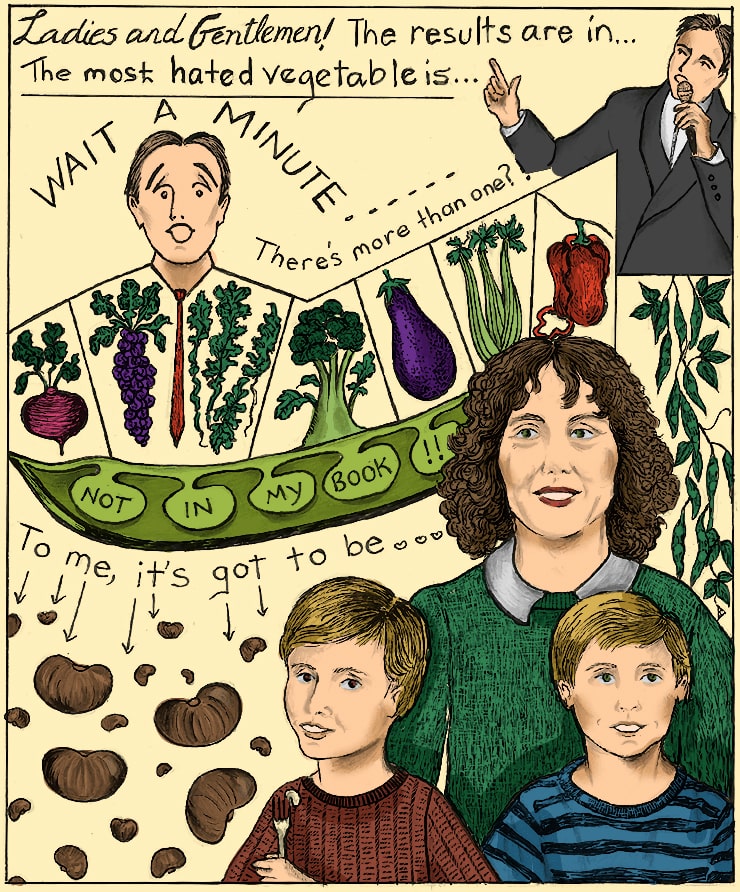

Almost everybody has a most hated vegetable.

For a lot of us, chances are it’s beets. Just 11% of home gardeners bother to grow beets, and professional farmers don’t do much better. Beet fan Irwin Goldman, Professor of Horticulture at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, estimates that just 8,000 acres of land in the U.S. are devoted to growing beets, which is a mere drop in the farmland bucket. We use nearly twice as much land for radishes, which says something.

Internationally, however, according to a range of surveys, the universally most loathed veggie is the Brussels sprout. (Practically everybody, everywhere, hates Brussels sprouts.) Comedian Jim Gaffigan, author of Dad Is Fat, hates kale. Ex-president George W. Bush famously hates broccoli. Kids turn up their noses at eggplant. The Brits don’t like celery. The Japanese don’t like bell peppers.

And I don’t like lima beans.

Not everybody, of course, agrees with me about lima beans. Author Laurie Colwin in More Home Cooking pronounced them “pillowy, velvety, and delicious.” Martha Rose Shulman in the New York Times raves over their “wonderful plush texture.” Thomas Jefferson thought them scrumptious. Even Fanny Trollope, author of the otherwise scathing Domestic Manners of the Americans, thought them “a most delicious vegetable.”

Fanny—mother of six, among them the wordy Victorian novelist Anthony—came to the United States in 1827 to build an early American version of a shopping mall in the then-frontier town of Cincinnati. The mall, then known as a fancy-goods bazaar, was a business disaster. Cincinnatians sneered at it and referred to it as “Trollope’s Folly.” By 1830, beset by creditors and teetering on the brink of financial ruin, Fanny decided—and who wouldn’t?—to save her bacon by writing a travel book.

The result, Domestic Manners of the Americans, published in 1832, was a rousing put-down of all things American. Spurned by Fanny were the Mississippi River (“a murky stream”), the writings of Thomas Jefferson (“a mighty mass of mischief”), tobacco (“repulsive”), hoe cakes (“intolerable”), watermelon (“vile”), and the obnoxious custom of serving chipped beef for tea. She complained that America lacked dinner parties and elevated conversation, and that American museums contained nothing but waxworks. Even Niagara Falls, Fanny found, was noticeably more sublime from the British side of the border.

The book was a bestseller. Fanny became comfortably rich, retired to an Italian villa, and lived happily ever after. Presumably—at least in part—on her praise of lima beans, which she urged Europeans to adopt.

They’re welcome to them is what I say.

Lima beans are commonly known as butter beans, a name said to be descriptive of the bean’s rich creaminess, though in my opinion it’s a cruel trick, intended to lure the unsuspecting into lima-bean-eating. Which—though this argument never worked on my mother—we shouldn’t do anyway, because lima beans, at heart, are poisonous. They contain cyanogenic glycosides, sugar-bound compounds that are harmless until cellular disruption occurs—as, say, when a lima bean is unwisely bitten—at which point an enzyme is released that chops the fatal molecule in two, releasing deadly hydrogen cyanide.

Granted, modern versions of lima beans contain much less cyanogenic glycoside than their closer-to-the-wild ancestors, and in any case, cooking does all in poisonous potential by reducing the cyanide-generating enzymes to impotent mush. But that’s not really the point. The point is that lima beans don’t want us to eat them. Basically, lima beans want us dead.

Scientists have yet to come up with a wholly viable explanation for why we hate some foods and adore others. In some cases, our genes may be at fault. According to recent studies, people who can’t stand cilantro—real haters claim it smells like soap and tastes like crushed bugs—have a cluster of genes that predispose them to dislike certain pungent tastes and odors. Presumably Julia Child had these, since she claimed the only reasonable thing to do with cilantro was throw it on the floor.

Genes also may put the kibosh on Brussels sprouts: A gene with the not-so-catchy name of TAS2R38, which affects our ability to taste bitter compounds, may put us off cabbage and relatives. To people with a certain form of TAS2R38, Brussels sprouts may just taste nasty.

If there’s an equivalent gene or genes for not liking lima beans, scientists haven’t found it yet—but if one exists, I share it with Bart Simpson and most of the U.S. Army who, during World War II, rejected C-ration-style ham and lima beans. In other words, I’m in good company.

I’ve got to admit, though, that there’s an upside to lima beans. They’re not entirely, unadulteratedly bad. They contain a com-pound called prunetin—which may hold the secret to a longer life. At least for males.

The studies—all right, they were done on fruit flies—showed that male flies, fed on prunetin, lived 10% longer than lima-bean-deprived, prunetin-less flies. (Extrapolated to a seventy-year-old man, that tacks on an extra seven years.) The prunetin-fed flies also had significantly lower glucose levels than their prunetin-less buddies—no diabetes risk for those flies—and they were far more physically fit, as evidenced by their ability to climb up the side of a test tube. Prunetin-fed flies climbed 54% faster than prunetin-less flies, which suggests that a whopping bowl of lima beans may be the thing to scarf down before a race.

From my point of view, though, the very best part of the lima-bean/prunetin study is that it works only in males. Female flies got no benefit at all from extra prunetin. This may be, the researchers suggested, because female flies already live longer than male flies; perhaps a dose of lima beans just allowed the lagging males to catch up. Or perhaps female flies have some kicky metabolic twist that obviates the need for prunetin.

The bottom line, though, looks pretty clear to me: Women don’t need to eat lima beans. I am so off the hook.

But I may just plant the awful things this year, anyway.

Not for me, mind you.

For my husband and sons. ❖

Previous

Previous