“Who would therefore look dangerously up at Planets, that might safely looke downe at Plantes?” asked John Gerard in his famous Herball of 1597.

What a comfort the garden can be in a turbulent, sometimes puzzling world. When Gerard was comforting himself with “the earth appareled with plants, as with a robe of embroidered worke, set with Orient pearles and garnished with great diversitie of rare and costly jewels,” views of his world were being turned over. His orderly universe was challenged by the shattering concept of contemporary scientists that, far from being the stable center of all things, the earth itself was moving and its companions, the “wandering stars” (planets) didn’t even travel in perfect circles. The flowers, though, bloomed safely below—as they always had.

Gardeners, like little children and poets, can enter into a small universe beneath them:

To see a World in a Grain of Sand

And Heaven in a Wild Flower

Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand

And Eternity in an hour

wrote William Blake. How lucky we gardeners are, especially in springtime, to be able to concentrate on miracles. Karel Capek, who wrote The Gardener’s Year in the late 1920s, lived in turbulent times: Hitler appointed Himmler and Goebbels as Nazi party leaders. Stalin was in power in the U.S.S.R. Meanwhile, Edwin Hubble discovered galaxies beyond the Milky Way and showed that they were moving away from the earth, and the universe itself is expanding.

Karel Capek was busy planting seeds, first marveling to his readers at the different seeds themselves: Some are “like blood-red fleas without legs;” others “thin like needles.” They can be “big like cockroaches,” and tiny “like specks of dust.” Big seeds don’t necessarily grow into large plants, or small ones into small plants. “I simply don’t believe it,” he writes. The world outside goes on; Capek is absorbed watching his seeds. He waits for the soil to be “silently forced apart,” and the tiny plant to emerge, miraculously “lifting the seed on its head like a cap.”

It’s the time of year for all of us to be planting seeds. As usual, I’ll put in a lot of nasturtiums, which must be the most rewarding flowers on earth: easy to grow, quick to flower—and spreading shield-like leaves that cover all garden mistakes! When first they came to Spain (1569), Nicholas Monardes described them in his book, New Founde Worlde. Each petal, he wrote, has a spot on it “like a droppe of bloode, so red and so firmly kindled in couller that it could not be more.”

Now I wonder how many of us (including me) have really noticed that red spot? The impressionist painter Claude Monet relied heavily on nasturtiums in his famous garden at Giverny, and he painted them, too, in glorious impressionist color. Did he notice Monardes’s spot? Anyway, this year I’m going to look closely for it, although maybe it has been hybridized out. But I’m going to look, really look down at the flowers in my garden.

Most flowers look up at the sun, their source of light and life. When I plant beans, they’ll shoot straight up towards the heavens. Unlike many of us, they don’t (I presume) wake up at 4:00 a.m. and start thinking of black holes, inter-space travel overtaking time, and the possible destruction of the earth’s atmosphere. They don’t presumably worry about their grandchildren, potential health issues, or their identity being stolen.

(I don’t worry much about my own identity being stolen. Who would want to be me, pottering around without an iPad, without a television, without a camera, talking—as you’ll see—to tomatoes? I don’t think there’d be many takers!)

I don’t grow all my plants from seed—especially not tomatoes. Last year, however, when I was clearing up the garden in late October, I came across a tiny tomato seedling under our picnic table. What could I do? “All right, you silly plant,” I said, and dug it up. I kept it in a pot all winter. As if in gratitude, it grew, and grew, and I had to prune it until it could go outside—where there was no stopping it. Eventually, it reached 15 feet high and 8 feet across (truly), covering everything around it and filling the porch gutter. It produced an abundance of small yellow tomatoes—not the best I have ever eaten, I admit. But it had already made a miracle. What more could I ask of it?

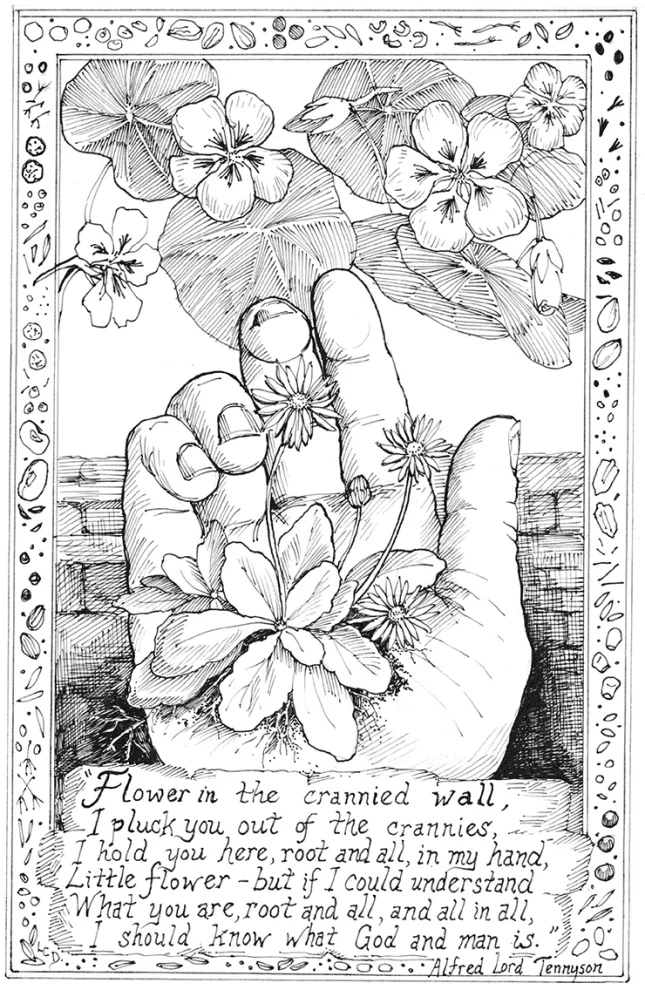

This year I’ll get some regular tomato plants, too. They come small, each one smaller by far than the fruit I hope to harvest from it. Like the poet Tennyson, I’ll cup the tiny plants in my hand and think about it all. Tennyson wasn’t gardening, but probably strolling when he spotted a Flower in a Crannied Wall. We know he wasn’t on a cell phone (in 1869), so he was looking and his hands were free:

Flower in the crannied wall,

I pluck you out of the crannies

I hold you here, root and all, in my hand,

Little flower—but if I could understand

What you are, root and all, and all in all,

I should know what God and man is.

Yes, these are turbulent times, and I for one don’t understand much of what goes on in the world outside my garden. I’m scared of my word processor (which has behaved well so far today) and can’t cope with email. I still like to pay bills by check. And if I’m depressed, I go into the garden to potter around.

And look. ❖

Previous

Previous