Read by Matilda Longbottom

the wind, the stronger the trees.

—J. Willard Marriott

Here where we live, on the Vermont side of northern Lake Champlain, we get a lot of wind. In the Summer, it whips the lake into whitecaps, rips the laundry off the line, and knocks the lawn furniture over. Wind is the reason for that dismal French Canadian sea shanty that ends, “You’ll never get drowned on Lake Champlain/As long as you stay on the shore.” Wind is the reason we put the vegetable garden on the sheltered side of the barn.

In the Winter, the wind comes straight down from the North Pole across the plains of Canada, makes a snow drift the size of a blue whale just off the back porch, freezes everything freezable solid, and buries the bird feeders.

Our wind is serious wind.

It could, of course, be a lot meaner wind. I just read that the strongest winds in the solar system are found on Neptune. There the wind whips frozen methane across the planet’s surface at speeds up to 1200 miles per hour, and temperatures hover around -392 degrees. Compared to Neptune, Vermont, even in February, is a beach on Tahiti.

And, for all my carping about frostbite, we can’t do without the wind.

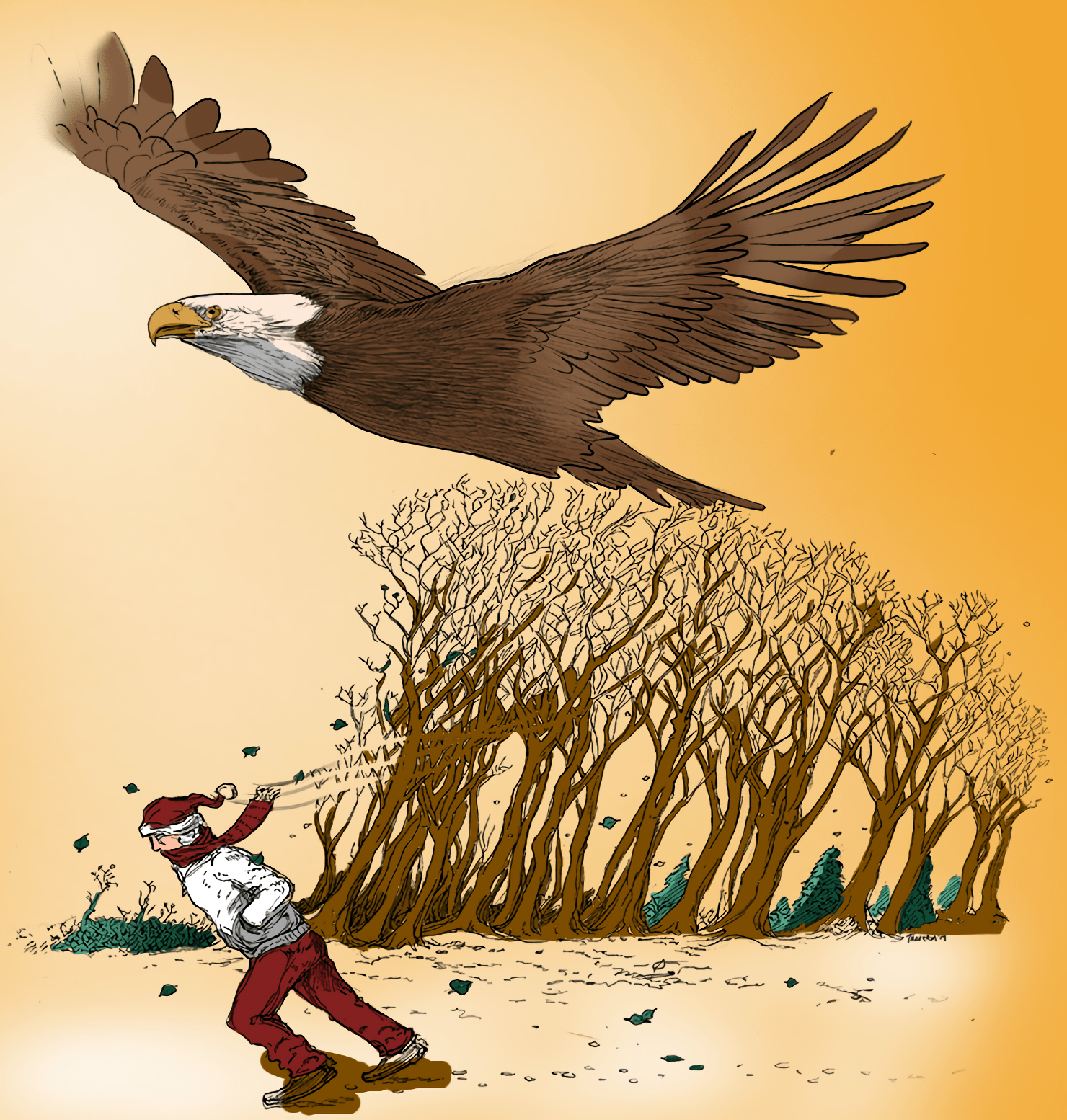

There’s an Abenaki legend in which the hero Gluscabi, bent on duck-hunting, is fed up with the wind that keeps blowing his canoe backwards. Annoyed, he tracks down the great Wind Eagle—whose flapping wings generate the world’s winds—ties his wings to his sides, and stuffs him into a crack in the mountainside. With the Wind Eagle out of commission, there’s no more wind—but soon the air is hot and stuffy, the water is dirty and stagnant, and a chastened Gluscabi learns the error of his ways.

We need the wind, even though I’d like to keep it away from our tomato cages, some of which are funny-shaped due to large doses of it. And the wind may be even more important for trees.

Which brings me to Biosphere 2. Biosphere 2—a three-acre, glass-and-metal greenhouse that looks like something out of Star Trek—is located in the desert outside Tucson, Arizona. It was initiated as a science experiment in the 1990s, the brainchild of philanthropist Ed Bass and ecologist John Allen, and was in-tended to be an enclosed self-sustaining environmental system, a replica in miniature of the Earth (Biosphere 1). It was the kind of structure, Bass and Allen hoped, that would eventually allow people to live on Mars.

In its heyday, Biosphere 2 was home to eight Biospherians (four men, four women), 3,000 plant and animal species, and seven different mini-biomes, among them a tiny tropical rainforest with its own 25-foot waterfall, a grassy savannah, a marshland, a desert, and a 150-foot-long ocean, complete with coral reef. (The rainforest supplied the Biospherians with coffee beans; the ocean provided their table salt.)

The Biosphere 2 experiment lasted less than two years before the whole thing melted down. A number of factors contributed to its demise, prominent among these soil bacteria multiplying at breakneck rates and pumping way too much carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. (The released Biospherians, gasping, said they’d never take oxygen for granted again.) Essential pollinating insect populations went extinct. Crops failed. And the trees started falling down.

Trees, it turns out, need wind.

When trees grow in the wild—that is, in the great outdoors of Biosphere 1—wind, the ultimate personal trainer, relentlessly keeps them moving. The continual mechanical push and shove—and occasional downright battering—by wind creates stress in the load-bearing structure of trees. That stress in turn causes a tree to dig in its heels and produce reaction wood, a stubbornly rigid, live-free-or-die-type wood that is particularly heavy in lignin. Lignin is an organic polymer—chemically a nightmarish snarl of ring-shaped molecules—that acts as a tree’s equivalent of cement. Reaction wood is how trees respond to aerodynamic bullying.

Reaction wood is a tree’s way of drawing a line in the sand. It’s obstinate and it’s tough. It’s what wind gets if it messes with trees.

The Biosphere 2 trees, deprived of wind, never developed reaction wood. They had no challenges, suffered no stress. Nothing shook them up. Biosphere 2, like an over-protective helicopter parent, never gave them the opportunity to test their mettle. The trees grew too tall, too fast, and had too little woody backbone. Gravity caught up with them and they toppled over.

I feel bad for those trees. Somebody should have intervened.

On the other hand, like Gluscabi’s disastrous goof with the Wind Eagle, there’s a lesson for us here, too.

Stress in the United States these days is at an all-time high. According to the latest Gallup poll, about 55% of American adults claim to experience stress for much of their day, as opposed to just 35% on average worldwide. We’re now as stressed as Greece, which has been topping the global stress charts since they lost the Olympics back in 2012.

Collectively we worry about money, health, family obligations, work performance, and (well, me) the speed at which our children drive. We agonize over all the things we’ve left undone. We worry—justifiably—about the future.

But that doesn’t mean we should give up.

Stress—dealt with in the right way—isn’t always bad.

Sometimes it gives us the impetus to do better. It motivates us to succeed. It inspires us to fight for what we think is right. It teaches us to deal with difficult situations. It gives us resilience and backbone.

Too much wind blows a tree over. But no wind does it no favors, either.

Same with us.

Stress isn’t all bad.

Sometimes it makes us tougher. ❖

Previous

Previous