I am not the fanatic gardener in my family. I am merely my husband’s assistant. His cheerleader. And, yes, some-times his critic:

“You’re starting how many tomato plants?”

“You do know blueberries are hard to grow.”

“How are we going to eat 24 heads of cauliflower?”

He is undeterred. He just keeps planning and planting. Before we purchased our property two years ago, we shared a garden a few miles away with Michael’s mother, who is also a fanatic gardener. She has a total of four gardens. Four gardens, I thought. That’s three too many.

Michael’s mother gardens with sweat, a tiller, a hoe, and an insatiable will. She has to: Her ground is hard and scattered with shale. She waters and fertilizes. She plants, stakes, and lays drip line. And she fills her freezers with the fruits of her labors.

Our garden there, due to an unwilling-ness on my part and lack of time on Michael’s, did not produce well. The tomatoes faltered. The Brussels sprouts sprouted bugs. The carrots never showed up.

Then we moved.

“It’s got a good garden,” the sellers told us when we looked at the property.

“That’s the best garden ground in the area,” said the neighbor lady.

“You should have seen that man’s garden,” said folks for miles around.

We listened, Michael eagerly, his assistant skeptically. And we bought.

It was too late to plant, though, here in central Pennsylvania. The next Spring, Michael planned, plowed, and planted. I held the baby and helped spread grass mulch to subdue weeds.

“That garden never grew weeds,” another neighbor said over the fence when he saw what I was doing.

I told the former owner’s son about this statement when he stopped by. His guffaw bounced off the cabbage heads. I decided to keep spreading grass.

“You can use all the water you want,” he assured me. “It’s a good well. Dad used to have four sprinklers going at once.”

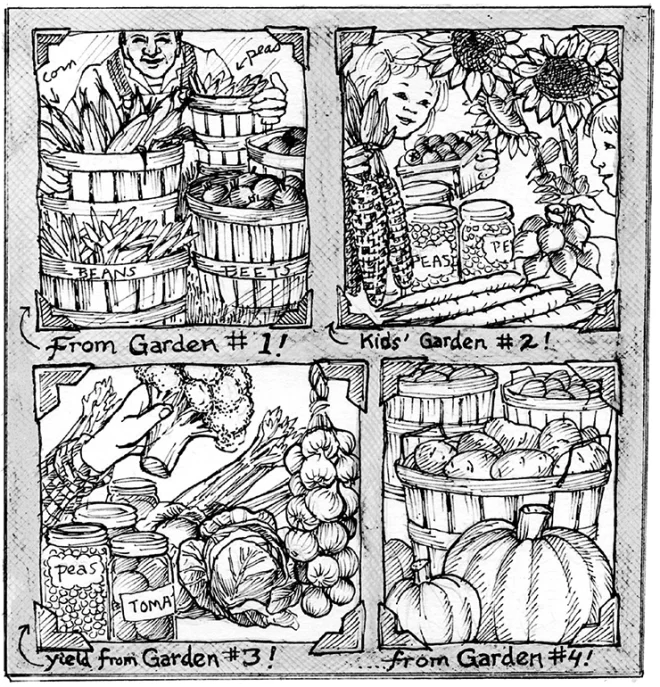

I told the family gardener. He brought drip tape and sprinklers. He watered. It rained. Things grew. We filled the garden with beans and peas and red beets and corn. The garden crowded our driveway on one side and the fence of the neighbor who never saw weeds on the other.

Our corn stalks grew so thick Michael was pulling suckers off. “I’ve never had corn grow suckers like this,” he worried.

His mother came over to look. “Those are ears,” she told him. They were—three or four to a stalk!

Michael dug a small patch on the other side of the grapevine for the children. They planted sunflowers, Indian corn, carrots, peas, cherry tomatoes, and radishes. And there we were, with no room for broccoli or onions or celery or cabbages or…

There was only one thing to do. Michael did it, late one night, with a borrowed plow.

The next day his dad drove past. When he got home, he told Mom, a little shocked: “Michael dug up a big patch of his front yard to plant a garden.”

“A well-kept garden can be as pretty as any front yard,” she answered. (Is “Like Mother, Like Son” a saying?)

That garden, too, filled quickly. And we had no place to grow potatoes. Surely the ground behind the house would do for potatoes. Michael plowed up a patch and planted potatoes. Soon pumpkins spread out next to the rows.

Some weeks later, I was standing at the sink washing the supper dishes and watching Michael hill up the potatoes. Idly I counted up our gardens—and stopped short. I counted again. There was the original garden, the one “unable to grow weeds.” One. There was the small children’s garden. Two. There was the garden in the front yard. Three. There was the potato garden behind the house. Four.

Four gardens. We had four gardens, just like Michael’s mom. How did we get here so quickly?

Note I said “we.” Perhaps I should blame the family fanatic gardener. But, I had to admit, they pulled at me, too. First the radishes from the children’s garden. Then the baby leaves of mesclun. The peas. The corn.

Michael’s mother came over to help husk and cream the corn. As she lifted the ears, dripping, from the cooling water, she said, “Ah, there’s nothing like the harvest.”

Nor was there. The real, tangible harvest. I ran to the garden to pull young onions. Fuzzy baby beans became impromptu lunches. Wee potatoes split their skins in the kettle, and I gilded them with butter.

Green beans came in. Tomatoes ripened. Our freezer filled with quarts of lima beans and broccoli. Salsa lined cellar shelves, jar after jar. Michael dug eight luxurious bushels of potatoes.

By November, the gardens were tired and ready for sleep. Our good dirt still yielded a few onions, some celery, a last handful of miniature cabbage heads, and what carrots had survived the moles. It was a good year.

Now it is January. “Let’s plant pole beans in the children’s garden so they can have a tent,” I suggest.

The broccoli did so well last year we have to grow it again,” Michael says. “Put more in the freezer.”

“Shall we try Brussels sprouts again? Perhaps in this ground, they will grow to maturity.”

“Let’s not leave in the middle of Summer this year.”

“We won’t be able to leave. It will be too much fun.”

“I saw something in a seed catalog …“

We dream of annuals: more peas, red beets to sell, turnips. We talk about perennials: blueberries, raspberries, strawberries, asparagus—definitely asparagus—rhubarb. Should we get beehives? Should we plant wheat? We plot the space in our minds, filling one garden after another with weed-free riches. Then we stop. We’ve reached the inevitable.

“Four gardens,” says the fanatic gardener to his assistant. “You know, that may be one garden too few.” He says it so enchantingly, and last year’s garden was so gorgeous, that—beyond all sense—I nod.

Can gardens be invasive like weeds? ❖

Previous

Previous