I suppose there are one or two people out there somewhere who are so perfectly organized that they actually keep all their gardening equipment in one easy-to-reach spot. Their hoe hangs right where it’s supposed to, the twine is neatly wound around two stout stakes, and the seed packets are all filed alphabetically in a shoe box. On the appointed day, they simply take out their equipment and plant a garden.

Not at this house. Ever. The day the first crow arrives, I begin to wonder where I left the hoe. And the rake—didn’t someone borrow it last Fall? Who?

About the same time I am ransacking the premises for garden tools, Friend Hubby begins hunting up garden hoses and water couplings and spray nozzles, none of which are ever connected to each other. And then he can’t find his gardening clothes, by which he means his sweater (a decrepit old tangle of tattered yarn), his shirt (stains on the sleeve, buttons missing, the back worn paper thin, and barbeque-spark holes in the front), his shoes (rundown, wrinkled, knot-laced, and with holes the size of a quarter), and his gardening pants (baggy-kneed, torn-pocketed, and fray-cuffed). When he steps outside, we don’t need a scarecrow!

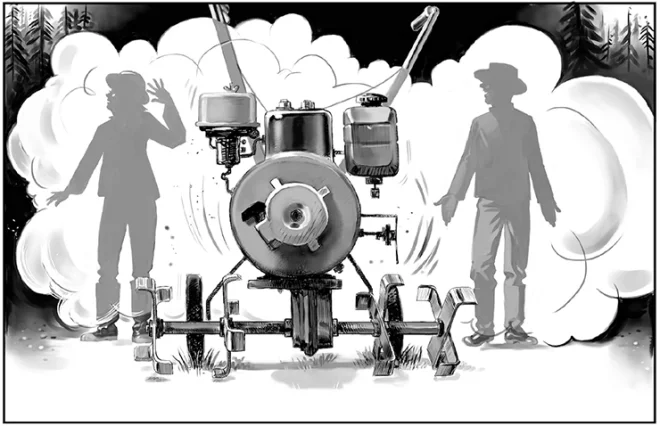

As Friend Hubby has done for the past 50 years, every Spring he unearths his garden tiller from beneath a pile of junk in the back yard. And every year I fully expect him to come in and solemnly announce that the old front-tined plowhorse has died.

So far it hasn’t happened. The old gal fires right up again this Spring. But then it starts to balk.

Friend Hubby comes in bearing a frayed starter rope and lamenting that he’ll have to pay four dollars for a new one.

I take a close look at the remains and identify them as being similar to a piece of cord I have among my sewing supplies.

“Is this long enough?” I ask.

Friend Hubby’s face lights up. “Sure! Can you spare it?” Spare it? I’m downright glad to get rid of it.

Friend Hubby goes back outside, beaming.

In a few minutes I hear him call: “Can you just help me thread that cord through this little hole?”

After a bit of finagling, I succeed.

“Now if you would just get the scissors and cut the end of this knot…”

He gives the cord a good tug and the motor springs to life, backfiring once or twice for good measure like a colt snorting for the pure joy of kicking up its heels. But then the tiller becomes a runaway steed—it just won’t stop.

“Give me that screwdriver!” shouts Friend Hubby.

I hand him the one with the insulated handle. He uses it to ground the spark plug. The motor coughs a bit, wheezes once or twice, and then comes to a full stop.

“Sounds as if you choked it to death,” I remark.

“Of course not!” retorts Friend Hubby. “I never even touched the carburetor. But that reminds me. You wouldn’t happen to have a spare sponge lying around, would you? I lost the one that belongs in the air breather.”

I give him a sponge from my cleaning cabinet to use as a filter. He cuts it to size. “Now this might work and it might not,” he tells me. “It might just smother it.”

He gives the new starter cord a pull.

The old tiller jumps to life once more, pawing the grass as if impatient to get going to the garden patch. But just in case it tries to get away from him again, Friend Hubby is keeping a tight rein on it, the insulated screwdriver protruding from the hind pocket of his gardening pants. I can’t say I blame him.

So now it’s time to plant. When the seed catalogs arrived back in January, I began my annual dream about that perfect garden we were going to grow this year. The rows would all be straight as arrows and not a weed on the premises.

But that was back in January. Come Spring, everything happens so fast I am utterly overwhelmed. The snow melts, the windows need washing, visitors arrive, the grass grows three inches a day, and the only blooms in sight are the dandelions.

Friend Hubby is not the least bit daunted. He has babied along a few dozen bedding plants for weeks and is anxious to set them out. I have to admit it will be nice to reclaim the dining room table he usurped for a makeshift greenhouse.

We set out with great planting expectations, as Friend Hubby meticulously strings a line to make straight rows. But then the sun goes under a cloud, and gardening becomes a race to beat the rain.

“Let’s just get those seeds in the ground and be done with it,” I cry.

“What if I just make the rows free hand?” he suggests.

“Fine with me. The peas will never know the difference.”

I stand at one end of the garden shouting directions.

“A little to the right, no, a bit left, that’s pretty good.” At the rate we’re going I figure we’ll be the only folks in the neighborhood whose rows are as wrinkled as they are.

One thing for certain: a marriage has never really been put to the test until the couple plants a garden together. Example? After 55 years of marriage and as many gardens, we still can’t come to an agreement as to how to plant cucumbers. The scenario goes something like this:

Friend Hubby says, “Should I make the cucumber hills here?”

“Why in hills? Why not rows?” “They grow better in hills.” “Who says?”

“That’s the way my mother always did it.”

At this point I will, if I’m smart, proceed with caution. You see, I must never, ever, say anything bad about my mother-in-law, even if she’s been dead for 40 years—especially since she’s been dead for 40 years. There is something about the way his mother did things that seems to appreciate over time, and it’s in the best interests of our relationship that I not question it.

We plant the cucumbers in hills.

That’s not the only point of contention. After we’ve planted 10 double rows of peas, one double row of beets, and another of beans, we come out one morning to find all of them nipped right off at ground level.

“I told you so!” exclaims Friend Hubby. “You and that cute little rabbit!”

“Well, he was cute. And he cleaned up all the seeds that fell from the bird feeder.”

“Humph! And now he’s cleaned out the garden.”

“Maybe it was a deer,” I suggest meekly.

“Pretty small deer, if you ask me. Look at the droppings.”

End of that argument.

We go buy a roll of chicken wire. Forty dollars. Four packages of bamboo stakes. Twenty dollars. Then we spend half a day figuring out how to erect a rabbit-proof fence. A dozen arguments. Sore fingers. Hurt feelings. A dearth of wire coat hangers to make hooks to hold the bottom edge of the chicken wire securely to the ground. Friend Hubby raids the closets.

“Do you need so many?” I protest.

“You know how fast a rabbit can dig?”

After replenishing and reseeding the peas, beets, and beans, Friend Hubby issues dire warnings. “So help me, if I find one rabbit on the place I’m gonna cut his tail off behind his ears!”

From then on, whenever I see a cottontail set foot on our property, I give chase.

“How come you’re so winded?” Friend Hubby asks one time when I come in.

“Must have been hoeing too fast, I guess.”

That night I hear raindrops peppering down on the roof, despite forecasts for a dry Spring. The rains persist for days. If Friend Hubby had not dug a drainage ditch all around the garden, the vegetables would be swimming in soil soup. The mosquitoes love it. They now have their very own moat to breed in. We try every conceivable suit of armor we can think of to thwart their attacks. Friend Hubby puts a grubby old jacket over his holey maroon sweater and zips it right up to the neck. Then he extracts his big red handkerchief from his hip pocket and drapes it from underneath the back of his baseball cap. And here I am beside him, doing my bug-shaking belly dance, my face veiled in an old mosquito-netted camouflage hat.

Despite all our slapping and swatting and mumbling and grumbling and aches and pains, we are firmly convinced that we are going to grow something valuable. The weather may be too dry, or too cold, or too wet, or too windy, but complaining about the heat and the bugs and the hail and the drought are as much a part of gardening as digging and planting and sowing and reaping.

I once saw a crooked old sign at a kid’s roadside stand that read “Vegtubbles—Home Groan.” And Friend Hubby and I do groan a lot.

But you know what? We’re blessed.

We get to groan—and grow—together. ❖

Previous

Previous