Read by Michael Flamel

Since I was old enough to remember, I wanted to have a farm, not 160 acres of corn, but a New England type, family farm—fruit trees, a berry patch, chickens, vegetable gardens, maybe a cow, bees, a greenhouse, a few pigs. Not that I knew anything about growing things. My expertise was limited to an annual bumper crop of dandelions in my lawn. Through my youthful and energetic years, I thought that raising plants and animals would be fun. Having currently passed the age of normal retirement without retiring from anything, I now knew that this kind of fun meant work, lots of it.

Four years ago, undeterred by the tasks ahead, my wife and I bought a small property outside Denver. Aside from a rundown shed that had once been used as a chicken coop, all farm amenities consisted of potential. It is seven acres, with a spring-fed lake, and zoned agricultural, wedged between the Platte River and I-76. Lying west, past the Platte, on the horizon, is Longs Peak, one of Colorado’s Fourteeners. On the east side is an upslope, giving our land topography and rendering the highway irrelevant. To our north and south are two families that keep horses, which we see more frequently than their owners.

My wife and I had been looking for suitable property for three years. Pam and I were looking for rural property for different reasons. She wanted to be free of immediate neighbors and carefree of what she wore, or didn’t wear, around the house. I wanted to develop a holistic, self-sustainable farm.

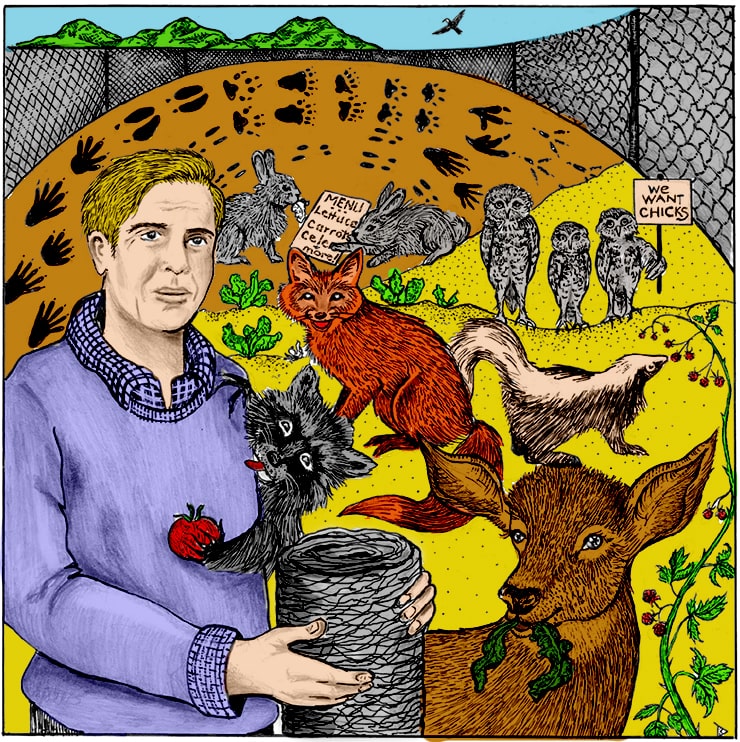

While images of an orchard and grape arbor intermingled with vegetables and livestock filled my head, reality forced me to think of how to protect plants and animals from plundering fox, deer, raccoon, skunk, owl, rabbit, and eagle. Early in the first season, I learned that much of my time would be spent fencing plants and animals, trying to keep some things in and other things out.

One of my first projects was to construct garden terraces on the steep eastern hillside. I went for the Mediterranean look—rock retaining walls, with grapes overflowing terraced cliffs, rising from sea to plateau above—minus the sea, the bluffs, or the grapes.

At some earlier time, truckloads of dirt and rock had been dumped in the field between the house and the lake. With a pick-axe, I dug through the piles, pulling out rocks of the right size and shape. The first season I built four terraces, laying up the stone dry and backfilling with topsoil. In two of the terraces, I planted raspberry bushes, acquired from a friend who was moving. In another I planted rhubarb. I sowed hollyhocks in the last, just because I like them and wanted some color.

As spring advanced, I checked on the new growth every few days. One day, I had to question my memory. I thought that the young hollyhocks were further along than they looked. I looked a little closer. New shoots were bitten off. Rabbits? Deer?

I erected a fence around the hollyhock using a roll of chicken wire and T-posts.

That solved the problem, but then I noticed that the rhubarb looked bothered. I was beginning to learn the sequential food choices of my vegetarian predators. I decided to put up one fence that included all the terraces. After that, the rest of the growing season was uneventful in terms of munching attacks.

The following year, I built five more terraces and added blue-berries, strawberries, cherries, and another patch of rhubarb. Once again I reconfigured the fencing to include all nine terraces.

Trees are a big contributor to any homestead, adding diversity, shade, safe haven, cooler temperatures, and beauty. Along with all my other duties, I planted evergreens along the crest of the hill, bamboo along the southern property line, and a variety of deciduous shade trees in the lawn.

Beside the driveway, down where it joins the road, a young loblolly pine I’d set out was having a hard time fending off the elements, including what I first thought were rude and careless drivers. Every so often I noticed that a small branch was broken and the trunk of the baby pine was scraped. I thought that one of the frequent drivers who weren’t sure where they were going turned around in our driveway and carelessly backed into the tree.

I held this belief until one morning, while preparing breakfast, I spotted a young buck rubbing its antlers against the little pine. Instantly, I apologized to the unknown driver in my head—and knew what I needed to do. With four T-posts and more chicken wire, I gave the pine tree its own private space. It is now on my two-page-long checklist of things that need seasonal attention. I mulch it twice a year and water it when needed. In response, the pine has nearly doubled in height and now displays dark green clusters on each branch, ready for spring growth.

Much of Colorado is high prairie, including Denver, sitting at the eastern foot of the Rockies. The ground is sandy and with little topsoil. I decided to build raised beds with improved topsoil for vegetables. And now, wiser to the ways of my animal friends, I knew that the beds would need to be enclosed.

A similar scenario was unfolding with the animals that I wanted to raise. I was busy wrestling with rolls of chicken wire for the coop when Dan drove up. I had recently met him at a bee-keeping workshop.

“Raccoons will climb that cottonwood tree,” he said. “Then they’ll go out on that limb, and drop into the yard. You also want to be sure the wire is buried. Skunks and fox will dig right under a fence if it’s not buried.”

Who was I to doubt him? Dan is a hunter and a fisherman and knows lots about wild animals. He doesn’t just hunt. He hunts with a bow and arrow. He hunts with a muzzle-loading musket. He hunts with a rifle. He does this each year—in two states. It was easy to believe him when he said that he didn’t buy meat in stores. I was just enclosing the chicken coop and yard with chicken wire to keep predators out. But I was proud of my handiwork and crestfallen when my friend informed me that I wasn’t half done with the real job at hand.

A few days later, another friend, a park ranger, dropped by as I was enclosing the newly constructed raised beds with sections of six-foot-high, chain-linked fencing to keep out the deer. Matter of factly she said, “Deer can clear eight feet.”

What kind of super athletes are these animals? Did I really have to consider the jumping, climbing, rappelling, and swoop-ing ability of all predators?

I was perplexed. How elaborate a system would I need to grow a little lettuce and a few tomatoes? To have a few chickens? I felt as though I had to defend my stock and garden from über-animals taught escape and evasion tactics at the Marines’ training camp. Evidently, these animals were able to do many things to breach my maximum security compound, which up until this moment had been known as a family farm.

I was beginning to wonder if growing my own food was even possible. I began restoring the chicken yard by raising the wiring to the same height on all sides—about nine feet. With fresh rolls of chicken wire and a stepladder, I began sewing strips of wire across the top, going the full distance from one side to the other. The task was tedious.

As I struggled with the sewing, my mind drifted to the objective of what I was trying to do—to protect a few plants and animals within my own property borders, to lay claim against nature for a particular meal. While it may seem trivial, it’s a serious matter, at least for my competitors. If I fail, I go to the grocery store. If I succeed, some animal must work harder for its next meal, which means it must get more aggressive and craftier to survive. More determined, more feral predators are now eyeing my meals.

After about twenty hours, the job was done. I slept well, knowing my chickens were safe from land, sea, and air attack.

For one night.

What to my wondering eyes should appear at dawn but ten inches of wickedly heavy, wet April snow in one of those freak spring Rockies snowstorms. I looked out the window to see my new chicken wire cage all caved in: The wet snow had clumped and stuck to the netting. It even bent inward the inch-and-a-quarter metal posts that supported the mesh. In many places, my barrier was down to half its original height. My wife and I went around with brooms whacking at the overhead snowdrifts, covering ourselves with icy snow in the process. I would have to build another structure made of 2x4s inside the existing cage to support the chicken wire throughout the yard. I felt like I was enacting some modern-day version of “The Three Little Pigs.” Mother Nature had huffed and puffed and blown my house down. But, hey, it was nothing another thirty hours couldn’t fix.

I did. I now have this lovely, maximum security compound. Nothing gets in or out without my permission.

Unless I forget to latch the gate. ❖

Previous

Previous

Thanks for the heart-warming essay. I especially liked the line, “ I felt as though I had to defend my stock and garden from über-animals taught escape and evasion tactics at the Marines’ training camp.”