There’s nothing equal to a flower garden in the woods for teaching children about life. So if you, too, are attempting to turn the herd of feral wildebeests you’ve fledged into moral (or at the very least, clothes-wearing) citizens of the world and are stuck in some horrible city, where outside means a grimy sidewalk, and nature is a crowded, well-tended park, I recommend you pick up stakes, orient your Pontiac Aztec’s nose north—and make for Maine.

True, your spouse will likely protest (“What were you thinking? Dragging me to this polar swamp!!!”). But trust me, your family will thank you…eventually. (Your family; I’m still hoping to hear “Maine was adequate”—preferably prior to my funeral.)

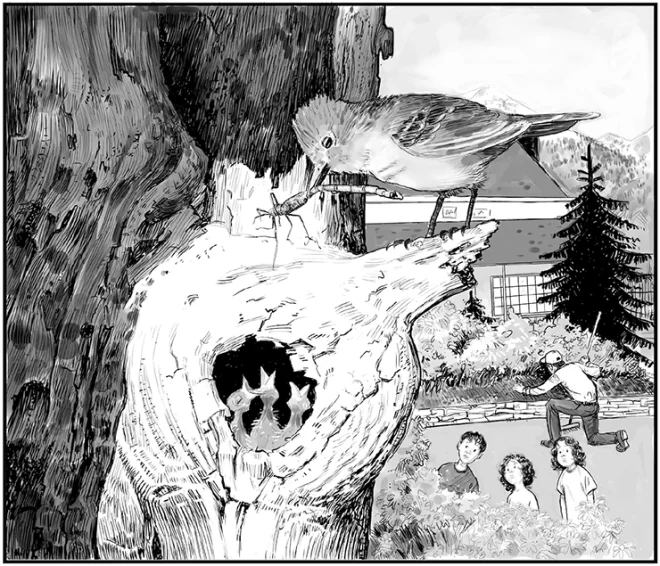

But to our tale at hand: This Spring, a pair of great crested flycatchers nested in a cedar near my latest garden project, a series of small beds bordered by rock steps. I was digging the day the birds arrived, and during breaks saw the female popping in and out of an old pileated woodpecker hole, no doubt measuring the place against the size of her planned nest. The male bobbed patiently up and down on a thin maple twig nearby, and gave only the occasional interrogatory tweet? (flycatcher for “Well? Well?”).

Apparently, the old bore hole was satisfactory. The nest was built, Mrs. Flycatcher moved in, and for the next couple of weeks I did my best to both not disturb her and to keep my pack of wildebeests from stampeding too loudly past the cedar. Before long, her efforts and mine were rewarded—tiny, urgent peeping noises could be heard emanating from the hole, and both parents began working overtime shoveling insects into their brood’s ever-empty mouths. Flies of all sorts were hunted to extirpation; the local dragonfly population took a serious hit; even the annoyingly ubiquitous Maine mosquito became hard to find.

As May has moved into June, the kids (twins Alena and Thomas, 5, and Tara, almost 4) and I have spent a lot time watching the flycatchers’ constant feeding. Our observations usually take place during work on the new flower beds, while Thomas “helps,” Alena asks (many) questions, and Tara runs around in the sun as naked and chubby as a cherub.

Today I’m trying to set in place a flat rock the size of a wagon wheel to serve as the bottom step of my little staircase. All three children are in my care—Katie’s at the store, in search of milk, birdseed, and sanity (or at least a break). As usual, the three of them are twittering away, making even more noise than the baby flycatchers.

“They sure eat a lot.” (Thomas)

“How many are in there?” (Alena)

“Actually, Papa, yesterday I saw the mama come back with an actual worm!” (Tara; ‘actually’ and ‘actual’ are the latest additions to her I’m-a-big-kid vocabulary. She’s determined to get as much mileage out of them as she can.) “I actually did!”

“They do eat a lot, buddy,” I say to Thomas, giving up for the moment on shifting the stubborn rock. The buds of a waist-high mountain laurel I planted last year are swelling, getting ready to explode into little pink stars. “They have a lot of growing to do, just like you guys. But in a couple of weeks, they have to be big enough to learn to fly. You ready to learn to fly?”

He giggles. Kindergarten is over for the year, the sun is shining, and he’s in the garden “working” with his Papa. Life for young Mr. Thomas is good.

“How many babies are there, Papa?” Alena asks again.

“Oh, I think birds usually have two to four. Can you imagine that, Miss Tara? Can you actually imagine actually having four little babies that you actually have to feed?”

Tara nods, her eyes round and very earnest. “I actually can.” “I bet you can,” I say, squatting down to her level. “Now, what do you say to putting on some clothes? How about, say, an actual t-shirt? Maybe some actual underwear?”

Two weeks later, July is near. My stairs and beds are finished, I’m transplanting bulbs, the fledglings are learning to fly, and the interest level of birding in the 3-to-5-year-old contingent has never been higher.

“There goes another one!” Thomas points. “He’s on that limb, see?”

“He actually flew! Did you see, Papa?”

“Actually, I did.”

“They really have to flap their wings fast!”

“Sure they do,” I say. “It’s like when you learned to ski last Winter. They have to build some muscle.”

“I actually learned how to ski the best.”

“It’s not a competition, Miss Tara. Everyone did really well, actually.”

“What happens if they can’t make it back to the nest?” Trust Alena to ask me that question—she was the one who gave me the third degree a few weeks ago, trying to suss out exactly how Mama and Papa Flycatcher made the eggs. I’d punted, putting off the whole birds-and-bees talk for a little older age, and even though I know this is a prime opportunity for talking about life and death in nature—I quickly decide to punt again.

“Oh, the mama and papa will help them,” I answer vaguely, then, as an extra precaution, I ask if anybody wants a snack, my failsafe for derailing possibly dangerous conversational trajectories.

So we snack. Then we run through the sprinkler a few times, eat lunch, take a short walk into the woods to look for more bird nests, return to the house, snack, watch a swarm of calliope hummingbirds, trim a few errant branches from the bottle-brush blue spruce in the front yard, and snack again. The afternoon has warmed without ever getting too muggy. Life is good.

It’s not until bedtime, when the midsummer sun has finally slid behind the bushy maples and towering pines and the shadows have dropped the bright green of the grass to a deep, dusky, almost blue, that disaster strikes.

Cowering on the weathered floor of our small back deck is one of the baby flycatchers.

Thomas spots the fledgling, and at first there’s a great deal of excitement—everyone gets a good chance to see the baby close up. Even Katie oohs and aahs before turning to me to ask, “Can we put him back in his nest?”

“We can try,” I say. I know how slim a fledgling’s chances are once it’s failed to return to the nest by night. But I put on a pair of old leather gloves and, with the whole family following at my heels, carry the baby back and tip him into the nest hole.

“Well,” I say, “that’s all we can do.”

“He’ll be okay, Papa, right?” Alena asks. “The mama and papa will help him so he can fly again, like you said. Right?”

I squat down. “I hope so, kiddo. We’ll check on him first thing in the morning, okay?”

That evening, I do two things I never do: I catch our barn cat and lock her in the garage overnight, and I set an alarm. I want to be the first to assess the scene.

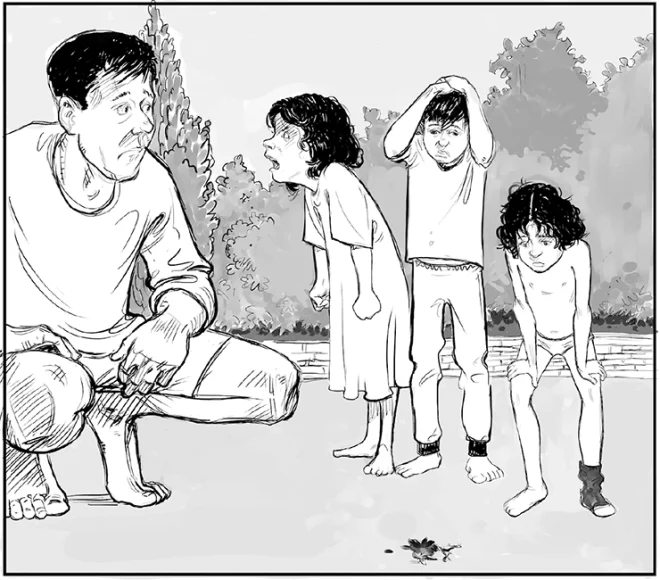

But as with most plans made by Amateur Child Tamers such as myself, my intentions fall through. Alena, excited and worried, not only wakes at the first gray of dawn, she drags Thomas and Tara with her. By five o’clock, when I stagger downstairs, my three barefoot, pajama-clad innocents—Tara, who of course sleeps in the nude, has deigned to put on a pair of underwear and her left sock to protect against the early morning chill—are already clustered at the base of the cedar, staring down at their first, feathered intimation of death.

Tears are flowing, copious and heart-breakingly genuine, from my brood, and for a moment I catch myself contemplating how I would feel losing any one of them.

Then, interrupting my dark thoughts, Alena erupts into bitter anger and accusations. My older daughter has gone full Dylan Thomas on me and is raging against the dying of the light.

“You said he would be OK!”

“No,” I say, as carefully and gently as I can, “I said I hoped so.” “You said the parents would take care of him!”

“Usually they do. Sometimes they do.”

She glares at me, her round face red, angry, and sodden, then suddenly bursts back into tears. “It’s not fair!”

Dang it, Papa, I think, you never should have punted in the first place. Having this conversation yesterday, before we were looking down at a little feathered corpse, would have at least somewhat prepared my daughter for this possible outcome. Now there’s nothing I can say.

Instead I gather her in for a hug, and she sobs until my t-shirt is wet against my shoulder and the skin on my forearms goose-bumps in the morning chill.

So there it is. Like I said, there’s really nothing like a garden in the woods for teaching children about life. But of course, part of life is death. And please, don’t ask me if my children are learning about it too early, or in the wrong manner—I have no idea. I’m an Amateur Child Tamer at best. On most days around here, we’re shooting for fully-clothed.

And hoping earnestly that they—and everything—will turn out OK. ❖

Previous

Previous

Good story! What those children will remember is the arms that comforted them for as long as they needed it. Your children are very lucky to live where and like they do, my bet is that they will grow up to be thinking, caring, resilient adults. Hang in there PaPa,

Lee B