I was talking recently with another grandmother. She had heard that you can raise your children either as if you were a “carpenter” or as if you were a “gardener.” Presumably this meant “according to rules,” or “with gentle nurturing.”

I’ve been thinking about this. I don’t know how I raised my own children. It seems, looking back, that they were little and then suddenly, after no time at all, they were grown, and I had not had much to do with how they turned out, although—whether I was a carpenter or a gardener—I am happy with the results.

Of course, I am a gardener—but I’m not sure about this implying that gardener-types are easy-going and not controlling and carpenter-types are more rigid. I haven’t been lucky enough to meet a carpenter recently, but if I did come across one, I would grab him/her and not let go (talk about controlling!). What I could do with someone who could replace shovel handles and mend fences and trellises, not to mention windows, chairs, tables, etc.!

In truth, actual gardening is always a way of controlling nature. Even so-called wild gardens are tended, cultivated, and controlled. Untouched nature has its own checks and balances and is often breathtakingly beautiful. But what was once cultivated or gardened and is now neglected is quite different—and you can’t achieve a lovely wild garden by simply doing nothing. I subscribe to several wild seed catalogs, one of which has a full page of instructions, warning customers that “casually broadcasting the seed over an unprepared area will only produce disappointing results.” I’ve been there—and I can tell you, they are right.

Planting wild seeds has a romance to it, like going back to Edenic times when flowers appeared like magic and all nature was a garden. And it’s good to grow native plants, good to try to give back youth to a tired Earth. But most gardeners want more than that. It’s hard for us to resist the showy flowers that were introduced from other places, or bred to bloom more generously, in new colors and for longer. Philosophically, we love the idea of nurturing what nature has provided on her own, but still, what about those gorgeous hybrids bred to attract the senses or resist diseases? And most flowers and vegetables are hybrids these days.

Hybridization, the epitome of horticultural control, was once thought to be actually sinful. It has occurred in nature for as long as, indeed longer than, the earth has been cultivated. Many a gardener or farmer has observed new and different plants. However, making them was a different story.

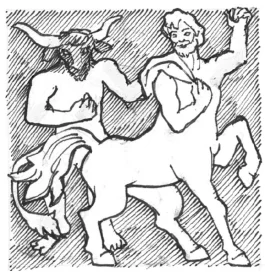

The ancient Jews forbade planting two kinds of seeds in the same vineyard—and also crossing donkeys and horses to produce mules (though they did use mules imported from other lands). The fear was that monsters might be produced if people played with nature. Indeed, in Greek legend, minotaurs and centaurs were made of such crosses. The word “hybrid” came from the Greek hubris, which first meant a combination of a wild boar and a tame sow, usually occurring when pigs roamed free. Later it became a derogatory term, sometimes referring to a child of a Roman father and a foreign (or even slave) mother.

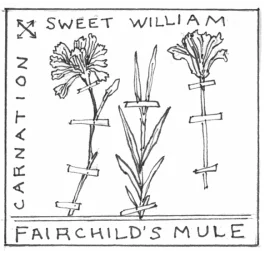

By Shakespeare’s time, there was an interest in plant hybrids. Perdita, in The Winter’s Tale, referred to “bastard” carnations and would not plant them. Shakespeare in a sonnet also described a pink rose that had “stolen” from a red and white one (it had to be a hybrid because grafts—which were common by this time—always stay true to color).

Thomas Fairchild, who lived from 1667 to 1729, is generally thought to be the first gardener to consciously hybridize two species. He crossed a carnation with a sweet William to produce a plant people called “Fairchild’s Mule.“ It did not attract much attention. But when Linnaeus published his findings on plant sexuality—useful information for hybridizing—he was widely condemned. Linnaeus hybridized many plants, including cannabis. But in a world thought to be immutable from its creation, he was sharply criticized, especially by the church (though he continued to attend church services, accompanied by Pompe, his dog).

By the mid-19th century, the famous Gregor Mendel experimented with peas, concluding that seeds could inherit characteristics from one “parent” or another. He was a monk and called the peas his “children.” But he was generally ignored and not taken seriously. Later, some people, like the Shakers, were still forbidden or criticized for hybridizing plants. Even Luther Burbank, creator of the Shasta daisy, was denounced by the clergy.

These days hybridization is common. Now we wrestle over problems like changing nature by manipulating genes. It’s nothing new: Gardeners have always tried to control nature and, I suppose, always will. So pretending that gardeners are less rigid than carpenters seems a bit deceptive. And I do believe that the children of either gardeners or carpenters might not be very easily distinguishable. (I’m pretty sure they can interbreed— “hybridize”—readily, as well.)

Myself, I am certainly a gardener and not a carpenter. As for my children, well, I won’t bore you by describing them—unless you want me to (do let me know, and be sure to leave plenty of time to listen…) ❖

Previous

Previous