Read by Matilda Longbottom

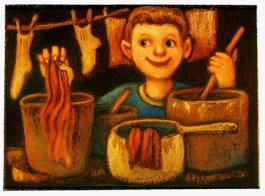

One year my children came home from summer camp excited about tie-dyeing. Although I was, of course, delighted that they had learned a craft and wanted to spend their time creatively, by the time it was all over my feelings were mixed. It’s one thing to have happy children make lovely things in a large space far away from home. When the temperature is 101° and a small kitchen is full of children filling every available saucepan with bright boiling liquid, you have to remind yourself that creativity is wonderful. When every sock, shirt, and pair of underpants is transformed into blotchy purple and orange (later to be rejected as ugly and unwearable), you have to be sure to remember that children’s expressive urges should not be frustrated. When the counter is cluttered with mayonnaise jars filled with dye which mustn’t be thrown out (until finally, in January, they are emptied into the snow), it’s time to unplug the TV in case you’re tempted to make them sit and watch all day.

Now apart from a disastrous morning with beetroot juice, the children used commercial dyes. At least we didn’t have to pick, pound, dig, and strain the dyes, which was the only way of obtaining them until the nineteenth century. So I didn’t have to make sure all my bloodroot wasn’t dug up or the marigold bed stripped. In the old days, it took as long or even longer to obtain the raw materials than to do the dyeing, but that didn’t stop people. We have been making and using dyes from prehistory-probably for as long as we have been making war.

Dyeing is one of the most ancient creative arts. As the Victorian garden writer Henry Phillips put it, “We find that barbarians who had neither learnt to cultivate the fruits of the earth, nor to raise themselves a shelter from the weather, would adorn their naked bodies by stain- been making and ing them of various colours.”

Caesar in the Gallic Wars says that “All Britons stain themselves with woad which grows wild and produces a blue color which gives them a ternble appearance in Battle.” Woad is not native to Britain, but we do not know how it arrived there or who first discovered its properties-a sophisticated discovery because the flowers of the plant are yellow, not blue, and the blue dye in the leaves is only revealed after they have been pounded, dried, pounded again, and fermented. The fermentation process smells so bad that it permeated whole towns. Queen Elizabeth I decreed that she would not pass near any such towns when touring the country, and no one could plant woad within five miles of any of her palaces.

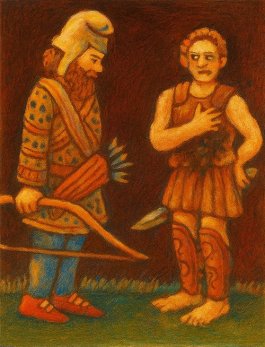

The wood industry was an important one in Britain until the introduction of indigo in the seventeenth century. At first indigo was not popular with dyers and it was called “Devil’s Dye” -implying obscure and unpleasant consequences for those who used it-but in the end it replaced woad. Blue was the basic dye color. For the “Saxon Green,” worn by Robin Hood, the cloth was first dyed blue and then overdyed with weld, a yellow dye obtained from wild mignonette. Purple could be obtained by overdyeing with madder. Madder is another ancient dye plant. When Alexander the Great was faced with a Persian army that outnumbered his, he had his soldiers dye their clothing with large blotches of madder dye. The Persian leaders reputedly took the blotches for bloodstains, thought the soldiers severely wounded, made very little effort to oppose them, and were consequently defeated.

The dye is obtained from the roots of the madder plant, which grows wild in Greece. It is still used to make artists’ paint. The most common colors yielded by plant dyes are brown, black, or grey. First settlers in America either imported dyes or used what was around. That’s probably why Puritans, Quakers, and all our good founding fathers wore drab colors-they were the only ones that native plants yielded. They were practical colors, too, because they hid dirt. In fact, the famous Quaker, John Woolman, objected to dyed clothes at all, saying, “Hiding that which is not dean by colouring our garments, appears contrary to the sweetness of sincerity.” The Spartans also forbade dyeing clothes, except their battledress, which they dyed scarlet so that bloodstains would be less visible.

The most common colors yielded by plant dyes are brown, black, or grey. First settlers in America either imported dyes or used what was around. That’s probably why Puritans, Quakers, and all our good founding fathers wore drab colors-they were the only ones that native plants yielded. They were practical colors, too, because they hid dirt. In fact, the famous Quaker, John Woolman, objected to dyed clothes at all, saying, “Hiding that which is not dean by colouring our garments, appears contrary to the sweetness of sincerity.” The Spartans also forbade dyeing clothes, except their battledress, which they dyed scarlet so that bloodstains would be less visible.

Most plants, even bright ones, yield dull or pale colors when used as dye. After browns or greys, pale yellows or pink are the easiest to obtain. You would think that pokeberries would yield a lovely purple dye, and it certainly looks that way when you squash one. Actually, it makes a dullish brown. The true bright pokeberry purple was one of the hardest colors to obtain with natural dyes, and in ancient times it was reserved for kings and nobility. It came not from plants but welks. Henry Phillips said the discovery of the purple dye “was owing to a dog, which, having caught one of tl1e purple fishes among the rocks, in eating it, stained his mouth and beard with the precious liquor; the blue thus acquired struck the facy of a Tyrian nymph so strongly, that she refused her lover Hercules any favours till he had brought her a mantle of the same colour.”

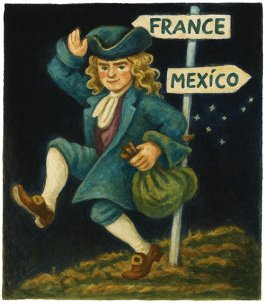

The cochineal insect was used in Mexico from ancient times to produce a bright red dye that far outshone any red obtained from plants. The Spaniards, when they conquered Mexico, jealously protected their monopoly over this dye. In the eighteenth century, the French government sent a Monsieur Menonville to steal cochineal insects from Mexico. Apparently, he obtained the insects but believed they fed on dahlias, which are also native to Mexico and have a red flower. The story is that he sent home the cochineal insects, which feed only on the opuntia cactus, with dahlia tubers, and of course all the insects died. The tubers, however, arrived safely and were planted in the Jardin des Plantes in Paris, where they were cultivated and introduced to European gardens. A nice story and I think of it every time I plant dahlias. Actually, red dahlia flowers do yield a red dye, but not the dear bright, cochineal red. Cochineal was used to dye the uniforms of the Buckingham Palace Guards until 1954.

I myself am a product of the sixties and an admirer of all things “natural.” Once I decided it would be lovely to have clothes dyed with vegetable dyes. It was rather a sudden decision, based on some dingy T-shirts I had just washed, and I didn’t seem to have, or want to dig up, the quantities of flowers or roots required. So I decided to start my experiments with onions, which are always mentioned in tomes about vegetable dyeing. The recipe started with a pound, not of onions, but onion skins. No one said how many pounds of actual onions had to be used up until there were enough flaky skins. I went to the supermarket and asked if they had any skins left on the onion shelves. The head of the produce department looked at me oddly, but he allowed me to scrape up a bag of skins.

You are also supposed to have what is called a “mordant” to fix the dye, and there’s usually a list of chemicals that Thrift Drug looks severe about if you inquire for them. I knew that our ancestors used vats of urine (called “chamberlye”) for a cheap and available mordant. There are records that 3,000 gallons a day of urine were collected in Glasgow for dyeing. It was certainly cheap, but availability seemed less assured when I approached my mother-in-law and teenage sons with the suggestion. My husband, as usual, was game for anything, but there was only one of him and, anyway, by now it appeared that garments dyed in homebrewed urine were not going to be greeted with the enthusiasm that their subtle natural shades should elicit. I decided to omit the mordant and use only the onions. What can I say? The books tell me that onion skins will produce a “golden tan” (so suitable for summer wear). But the T-shirts ended up the same yellowish hue they were to begin with, so maybe I should have used a mordant after all ….

Of course with dyes, as with anything else, the fact that something is “natural” doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s better. Indigo (a member of the pea family) reacts with human perspiration to produce an unpleasant smell-a disadvantage in a shirt.

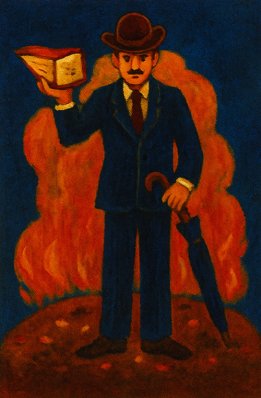

You need 70,000 dried cochineal bugs to make one pound of red dye, and saffron, which was a precious source of yellow dye in past times, requires 4,000 crocuses to produce just one ounce. This meant not only that the best dyes were restricted to the few well-to-do, but there was also a temptation to adulterate them. In 1444 a man was burned alive in Nuremberg (along with his sacks of merchandise) for adulterating saffron. Even for common plants, astonishing numbers are often needed to make a dye. One wonders if they aren’t better left undisturbed.

The discovery of the first chemical, or aniline, dye in 1856 was greeted with tremendous excitement. It was called “mauve” by William Perkins who discovered it accidentally when searching for synthetic quinine to replace the bark of the cinchona tree for treating malaria. He quickly saw the potential of synthetic dyes, and mauve became the rage. Queen Victoria wore a mauve dress to the Great Exhibit in 1862, and a new mauve penny postage stamp was issued.

When I first came to live in America, my mother-in-law told me firmly that she preferred orange cheddar cheese. Now I come from England where the cheddar cheese, like the heroic Englishman, is pale and strong, and moreover, as I have said, I was into “natural” products. For a while I bought two varieties of cheddar since neither of us would compromise. In the end, though, my children, little Americans that they were, also demanded orange cheese. About that time, I discovered that dairy products, including cheese, are colored with annatto, a natural plant product from the Bixa orelana, a tropical tree of the Indies. So now we eat orange cheese. But I sometimes wonder. We are all suckers for anything “natural,” and gardeners are no exception. Rotenone, a powerful fish poison, and copper sulphate are sold as “natural” garden sprays. But curare, hemlock, and toadstools are also natural-as natural as dying ….

The great advantage of plant dyes is perhaps not their “natural” qualities but the subtleness of their colors. To us, satiated with strong aniline dyes and colors, with glossy photographs and neon plastics, subtlety has become something we long for. Nowadays, we can even have our breakfast cereal in rainbow hues. Gone is the necessity of endlessly cultivating, collecting, pounding, boiling, sifting, in an attempt to transfer some of the brightness of nature to our daily lives.

Would our ancestors have taken us all for kings if they could have seen our clothing? Perhaps they might just have marvelled at the dullness of our senses as we so casually handle, in every aspect of our daily lives, a kaleidoscope of unimaginable brilliance. ❖

Previous

Previous