When after almost a year away, I climbed back into my own bed, I immediately felt a sense of homecoming. My bed was, in the words of Goldilocks, “just right.”

We spend about a third of our lives in bed. We are (usually) born in bed and die in bed. No wonder that we love our beds. In the past, people would even leave their beds in their wills.

Beds have not always been the sophisticated structures we know now. The earliest beds may have been hollows dug in the earth and filled with leaves. The early word bhedh means “a grave”—a place where the dead slept dug into the earth. Beds, as we now think of them, date back to four centuries before Christ—and were only for the rich and powerful (and often shared by several people). Others slept on pallets stuffed with straw. When Christ said, “Take up thy bed and walk,” it would have been a pallet or even a litter (the French word for bed is lit). The ancient Greeks believed that a bed should be smoothed out after the night—to prevent an enemy from stabbing the body’s imprint on the mattress.

What about in the garden? True, flowerbeds are places where your plants are protected and seeds can cozily sleep until it is warm enough to wake. The term, however, most probably evolved from their shape, rather than the connotation of safety and warmth. Even ancient gardeners created separate spaces for growing flowers, sometimes outlining elaborate patterns, similar to embroideries. Christopher Marlowe described one such garden layout as looking like a “costly valence o’er a bed.” Before hardy annuals were abundant, the patterned spaces might be filled with grass or even colored glass or gravel.

In the 19th century, an influx of bright tropical plants revolutionized flower beds. In Britain, “bedding out” became popular and dominated gardens for a century. This trend accelerated when, in 1847, the tax on glass was repealed and it became cheaper to build glass houses where tropical plants could be raised and protected until it was warm enough to plant them in outdoor beds. There they bloomed nonstop until the frost killed them (unless they could be dug up and brought inside).

These new beds rivaled each other in intricacy and brilliance and were sometimes called “carpet beds” because the plants were of equal height and formed into complicated patterns such as clocks or coats of arms. One such garden in a house in Clapham was said to contain 60,000 plants, where “brilliance is combined with chasteness.” (One wonders about the latter!)

We still use tropical plants in Summer beds, but, except in municipal parks or the like, we mostly don’t make elaborate patterns. These fell out of favor at the end of the 19th century when “wild gardens” became popular. The revolution against bedding out was said to have started when William Robinson, a young Irish gardener, allowed the furnace in his employer’s greenhouse to go out, then opened the windows and left—supposedly as a protest against what he called a “repulsively gaudy” garden system. He started a kind of gardening that restored “Nature’s ways of displaying the beauty of vegetation.” In time, these so-called “herbaceous” borders, a mix of shrubs and perennials, mostly replaced formal beds.

We still have beds and often plant them with seeds of tender annuals to come up as the weather warms or with already flowering plants that fill nurseries in the Spring. Our flower beds are safe, warm enclosures packed with brightness—or so we hope.

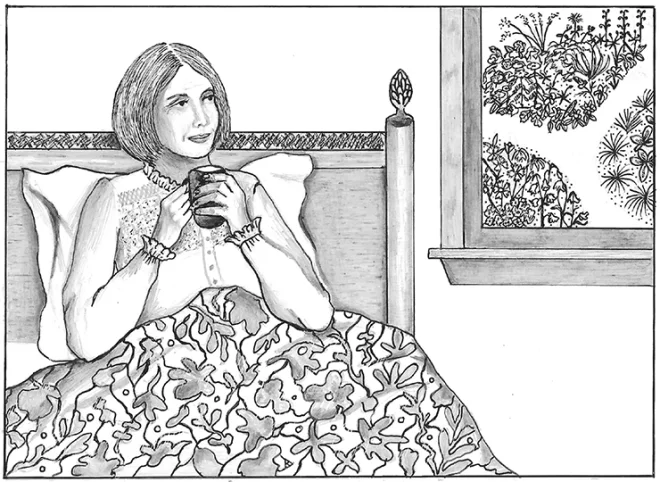

Tucked in my own bed, sipping a cup of early morning tea, was the moment I finally began to take in that I was really home. Things would never be the same again, but I was also coming back to my own sadly neglected garden. Yes, I would be planting flowers again, making a safe haven for them and, I hope, being rewarded with their brilliance. Being rewarded, maybe, after a bleak, bleak year, with perhaps a reason to hope again. ❖

Speaking of beds, Diana thought we would all enjoy this classic garden bed poem by A.A. Milne (from his 1924 poetry collection, When We Were Very Young). And you know what? I think she’s right! Here it is.

Previous

Previous