After six months of living in roach motels, selling my blood for money, camping out with bedsheets and blankets, and even pondering the idea of getting a job in a whorehouse, I decided that enough was enough. In the Spring of 1970, I came back to New York. Tired of living a crazy and dangerous vagabond existence with my boyfriend in Nevada and California, I finally broke up with him at Yellowstone National Park, called my mother, and asked for a ticket home. She wired money and a plane ticket without asking me a single question. It was one of the most generous and loving things she ever did.

My parents hoped I would finally resign myself to their fate: NYU, motherhood, and the suburbs of Long Island. While I recovered from my adventures with Bob, I took a job on the Upper East Side as the receptionist for an upscale podiatrist and his clientele of wealthy retirees, dancers, and assorted other bunion bearers. I had always harbored an abhorrence of feet, so I never saw this job as a permanent career move, but I did enjoy the brunches of delicate imported cheeses and wafer-thin crackers in the X-ray room. (And I was amazed at the backroom affair going on in semi-secret between the podiatrist and his nurse.)

In a strange way, working in the city became a way of bonding with my father—who had commuted to and from New York every day of his working life. Now I joined him in waking up at 6:00 a.m. We’d drive from Wantagh to Queens to catch the Long Island Railroad to Penn Station, where we would take separate subway trains to different destinations. Then I’d walk another four or five blocks to the office. In the evening, I would take the subway back to Penn Station and meet my father for the train to Queens and the drive back out to Long Island in time for dinner and bed.

It was grueling and a far cry from walking among the hot pools and geysers at Yellowstone and heeding the grizzly warnings at night. My dreams of living in the fresh air of the Rocky Mountains with the then love of my life had disintegrated into stinky feet and calluses and the underground air and agitated distress of the city.

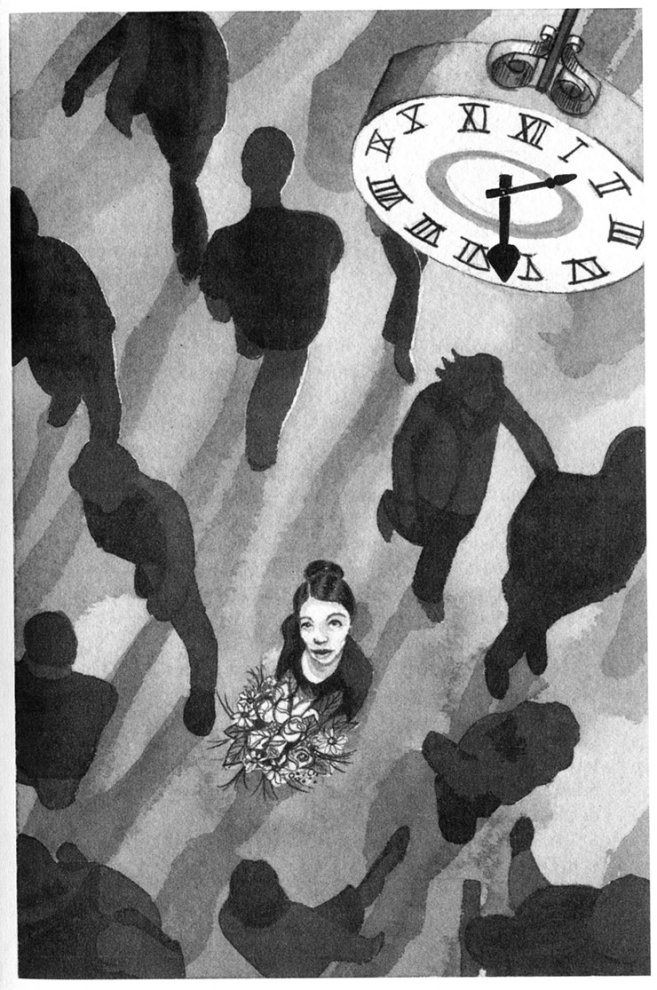

One February evening, while I was waiting in Penn Station for my father, I wandered off to look at kiosks and newsstands scattered throughout its vast center room. Unexpectedly, through the fog of swarming commuters and the rumble of trains and feet, my nose caught the sweet green scent of flowers.

In a trance, I wandered closer to the smell. There, in the middle of all the chaos, was a flower stall. I stood still, my gaze narrowing to that oasis of sweetness and natural perfume in the midst of this underground cavern of cement and fluorescent lights. Suits and briefcases jostled me as people rushed by. The overhead speakers blared unintelligible track numbers, arrivals, and delays. But I was fixated on the jubilation of colors and shapes, of red roses and lilac delphiniums, of sun-drenched daffodils and white daisies. How I missed the sound of the wind in the ponderosa pines and the acrid smell of sulphur pools and sun-warmed rocks!

I vaguely remember a grey-suited figure who broke out of the crowd and moved in toward the stall. I paid no attention, though, until something was shoved into my arms. I looked down into a giant bouquet of flowers. When I recovered from the shock and looked up, I was only able to catch a glimpse of the man and his briefcase disappearing into the crowd. I stood there in the center of chaos, surrounded by light.

So, To Whom It May Concern, I have always been in love with you. Thank you for giving me back my dreams. Happy Valentine’s Day, ❖

Previous

Previous